Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

14 May 2019

Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imagingMarie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches https://doi.org/10.1101/425561OB-GYN for salmon parrsRecommended by Jean-Olivier Irisson based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population dynamics and stock assessment models are only as good as the data used to parameterise them. For Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations, a critical parameter may be frequency of precocious maturation. Indeed, the young males (parrs) that mature early, before leaving the river to reach the ocean, can contribute to reproduction but have much lower survival rates afterwards. The authors cite evidence of the potentially major consequences of this alternate reproductive strategy. So, to be parameterised correctly, it needs to be assessed correctly. Cue the ultrasound machine. Through a thorough analysis of data collected on 850 individuals [1], over three years, the authors clearly show that the non-invasive examination of the internal cavity of young fishes to look for gonads, using a portable ultrasound machine, provides reliable and replicable evidence of precocious maturation. They turned into OB-GYN for salmons (albeit for male salmons!) and it worked. While using ultrasounds to detect fish gonads is not a new idea (early attempts for salmonids date back to the 80s [2]), the value here is in the comparison with the classic visual inspection technique (which turns out to be less reliable) and the fact that ultrasounds can now easily be carried out in the field. Beyond the potentially important consequences of this new technique for the correct assessment of salmon population dynamics, the authors also make the case for the acquisition of more reliable individual-level data in ecological studies, which I applaud. References. [1] Nevoux M, Marchand F, Forget G, Huteau D, Tremblay J, and Destouches J-P. (2019). Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging. bioRxiv 425561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/425561 | Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging | Marie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches | <p>Salmonids are characterized by a large diversity of life histories, but their study is often limited by the imperfect observation of the true state of an individual in the wild. Challenged by the need to reduce uncertainty of empirical data, re... | Conservation biology, Demography, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Jean-Olivier Irisson | 2018-09-25 17:24:59 | View | ||

14 Nov 2022

Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture modelsCécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719A new and efficient approach to estimate, from protocol and opportunistic data, the size and trends of populations: the case of the Pyrenean brown bearRecommended by Nicolas BECH based on reviews by Tim Coulson, Romain Pigeault and ?In this study, the authors report a new method for estimating the abundance of the Pyrenean brown bear population. Precisely, the methodology involved aims to apply Pollock's closed robust design (PCRD) capture-recapture models to estimate population abundance and trends over time. Overall, the results encourage the use of PCRD to study populations' demographic rates, while minimizing biases due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. Estimating the size and trends of animal population over time is essential for informing conservation status and management decision-making (Nichols & Williams 2006). This is particularly the case when the population is small, geographically scattered, and threatened. Although several methods can be used to estimate population abundance, they may be difficult to implement when individuals are rare, elusive, solitary, largely nocturnal, highly mobile, and/or occupy large home ranges in remote and/or rugged habitats. Moreover, in such standard methods,

However, these conditions are rarely met in real populations, such as wild mammals (e.g., Bellemain et al. 2005; Solbert et al. 2006), and therefore the risk of underestimating population size can rapidly increase because the assumption of perfect detection of all individuals in the population is violated. Focusing on the critically endangered Pyrenean brown bear that was close to extinction in the mid-1990s, the study by Vanpe et al. (2022), uses protocol and opportunistic data to describe a statistical modeling exercise to construct mark-recapture histories from 2008 to 2020. Among the data, the authors collected non-invasive samples such as a mixture of hair and scat samples used for genetic identification, as well as photographic trap data of recognized individuals. These data are then analyzed in RMark to provide detection and survival estimates. The final model (i.e. PCRD capture-recapture) is then used to provide Bayesian population estimates. Results show a five-fold increase in population size between 2008 and 2020, from 13 to 66 individuals. Thus, this study represents the first published annual abundance and temporal trend estimates of the Pyrenean brown bear population since 2008. Then, although the results emphasize that the PCRD estimates were broadly close to the MRS counts and had reasonably narrow associated 95% Credibility Intervals, they also highlight that the sampling effort is different according to individuals. Indeed, as expected, the detection of an individual depends on

Overall, the PCRD capture-recapture modelling approach, involved in this study, provides robust estimates of abundance and demographic rates of the Pyrenean brown bear population (with associated uncertainty) while minimizing and considering bias due to inter-individual heterogeneity in detection probabilities. The authors conclude that mark-recapture provides useful population estimates and urge wildlife ecologists and managers to use robust approaches, such as the RDPC capture-recapture model, when studying large mammal populations. This information is essential to inform management decisions and assess the conservation status of populations.

References Bellemain, E.V.A., Swenson, J.E., Tallmon, D., Brunberg, S. and Taberlet, P. (2005). Estimating population size of elusive animals with DNA from hunter-collected feces: four methods for brown bears. Cons. Biol. 19(1), 150-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00549.x Nichols, J.D. and Williams, B.K. (2006). Monitoring for conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21(12), 668-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.007 Otis, D.L., Burnham, K.P., White, G.C. and Anderson, D.R. (1978). Statistical inference from capture data on closed animal populations. Wildlife Monographs (62), 3-135. Solberg, K.H., Bellemain, E., Drageset, O.M., Taberlet, P. and Swenson, J.E. (2006). An evaluation of field and non-invasive genetic methods to estimate brown bear (Ursus arctos) population size. Biol. Conserv. 128(2), 158-168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2005.09.025 Vanpé C, Piédallu B, Quenette P-Y, Sentilles J, Queney G, Palazón S, Jordana IA, Jato R, Elósegui Irurtia MM, de la Torre JS, and Gimenez O (2022) Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models. bioRxiv, 2021.12.08.471719, ver. 4 recommended and peer-reviewed by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.12.08.471719 | Estimating abundance of a recovering transboundary brown bear population with capture-recapture models | Cécile Vanpé, Blaise Piédallu, Pierre-Yves Quenette, Jérôme Sentilles, Guillaume Queney, Santiago Palazón, Ivan Afonso Jordana, Ramón Jato, Miguel Mari Elósegui Irurtia, Jordi Solà de la Torre, Olivier Gimenez | <p>Estimating the size of small populations of large mammals can be achieved via censuses, or complete counts, of recognizable individuals detected over a time period: minimum detected (population) size (MDS). However, as a population grows larger... |  | Conservation biology, Demography, Population ecology | Nicolas BECH | 2022-01-20 10:49:59 | View | |

02 Dec 2021

Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289The promise and limits of DNA based approach to infer diet flexibility in endangered top predatorsRecommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond based on reviews by Francis John Burdon and Babett GüntherThere is growing evidence of worldwide decline of populations of top predators, including marine ones (Heithaus et al, 2008, Mc Cauley et al., 2015), with cascading effects expected at the ecosystem level, due to global change and human activities, including habitat loss or fragmentation, the collapse or the range shifts of their preys. On a global scale, seabirds are among the most threatened group of birds, about one-third of them being considered as threatened or endangered (Votier& Sherley, 2017). The large consequences of the decrease of the populations of preys they feed on (Cury et al, 2011) points diet flexibility as one important element to understand for effective management (McInnes et al, 2017). Nevertheless, morphological inventory of preys requires intrusive protocols, and the differential digestion rate of distinct taxa may lead to a large bias in morphological-based diet assessments. The use of DNA metabarcoding on feces (or diet DNA, dDNA) now allows non-invasive approaches facilitating the recollection of samples and the detection of multiple preys independently of their digestion rates (Deagle et al., 2019). Although no gold standard exists yet to avoid bias associated with metabarcoding (primer bias, gaps in reference databases, inability to differentiate primary from secondary predation…), the use of these recent techniques has already improved the knowledge of the foraging behaviour and diet of many animals (Ando et al., 2020). Both promise and shortcomings of this approach are illustrated in the article “Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)” by Quereteja et al. (2021). In this work, the authors assessed the nature and spatio-temporal flexibility of the foraging behaviour and consequent diet of the endangered petrel Procellaria westlandica from New-Zealand through metabarcoding of faeces samples. The results of this dDNA, non-invasive approach, identify some expected and also unexpected prey items, some of which require further investigation likely due to large gaps in the reference databases. They also reveal the temporal (before and after hatching) and spatial (across colonies only 1.5km apart) flexibility of the foraging behaviour, additionally suggesting a possible influence of fisheries activities in the surroundings of the colonies. This study thus both underlines the power of the non-invasive metabarcoding approach on faeces, and the important results such analysis can deliver for conservation, pointing a potential for diet flexibility that may be essential for the resilience of this iconic yet endangered species. References Ando H, Mukai H, Komura T, Dewi T, Ando M, Isagi Y (2020) Methodological trends and perspectives of animal dietary studies by noninvasive fecal DNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 2, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.117 Cury PM, Boyd IL, Bonhommeau S, Anker-Nilssen T, Crawford RJM, Furness RW, Mills JA, Murphy EJ, Österblom H, Paleczny M, Piatt JF, Roux J-P, Shannon L, Sydeman WJ (2011) Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion—One-Third for the Birds. Science, 334, 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212928 Deagle BE, Thomas AC, McInnes JC, Clarke LJ, Vesterinen EJ, Clare EL, Kartzinel TR, Eveson JP (2019) Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 28, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14734 Heithaus MR, Frid A, Wirsing AJ, Worm B (2008) Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.003 McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347, 1255641. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641 McInnes JC, Jarman SN, Lea M-A, Raymond B, Deagle BE, Phillips RA, Catry P, Stanworth A, Weimerskirch H, Kusch A, Gras M, Cherel Y, Maschette D, Alderman R (2017) DNA Metabarcoding as a Marine Conservation and Management Tool: A Circumpolar Examination of Fishery Discards in the Diet of Threatened Albatrosses. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00277 Querejeta M, Lefort M-C, Bretagnolle V, Boyer S (2021) Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). bioRxiv, 2020.10.30.360289, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289 Votier SC, Sherley RB (2017) Seabirds. Current Biology, 27, R448–R450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.042 | Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica) | Marina Querejeta, Marie-Caroline Lefort, Vincent Bretagnolle, Stéphane Boyer | <p style="text-align: justify;">As top predators, seabirds can be indirectly impacted by climate variability and commercial fishing activities through changes in marine communities. However, high mobility and foraging behaviour enables seabirds to... |  | Conservation biology, Food webs, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Sophie Arnaud-Haond | 2020-10-30 20:14:50 | View | |

06 Mar 2020

The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategiesCharlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux https://doi.org/10.1101/790634The importance of spatio-temporal dynamics on MPA's designRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Ana S. L. Rodrigues and 1 anonymous reviewerMarine protected areas (MPA) have arisen as the main approach for conservation of marine species. Fishes, marine mammals and birds can be conservation targets that justify the implementation of these areas. However, MPAs undergo many of the problems faced by their terrestrial equivalent. One of the major concerns is that these conservation areas are spatially constrained, by logistic reasons, and many times these constraints caused that key areas for the species (reproductive sites, refugees, migration) fall outside the limits, making conservation efforts even more difficult. Lambert et al. [1] evaluate at what point the Bay of Biscay MPA contains key ecological areas for several emblematic species. The evaluation incorporated a spatio-temporal dimension. To evaluate these ideas, authors evaluate two population descriptors: aggregation and persistence of several species of cetaceans and seabirds. References [1] Lambert, C., Dorémus, G. and V. Ridoux (2020) The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies. bioRxiv, 790634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/790634 | The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies | Charlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux | <p>The main type of zonal conservation approaches corresponds to Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are spatially defined and generally static entities aiming at the protection of some target populations by the implementation of a management pla... |  | Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Species distributions | Sergio Estay | 2019-10-03 08:47:17 | View | |

23 Oct 2023

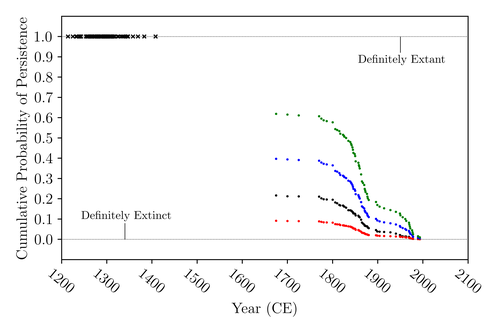

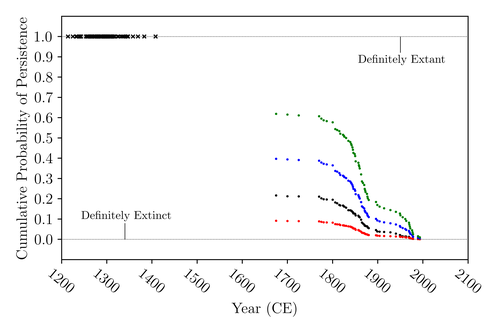

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

14 Jun 2024

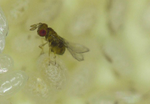

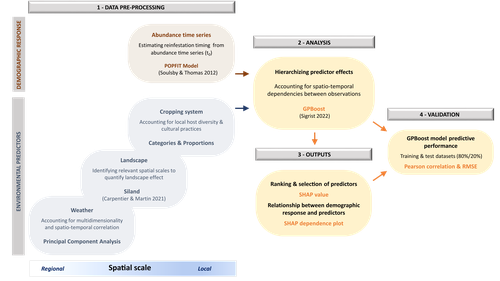

Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of Bactrocera dorsalis population growth in Senegalese orchardsCécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.10.566583Uncovering the ecology in big-data by hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effectsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Jianqiang SunAlong with the generalization of open-access practices, large, heterogeneous datasets are becoming increasingly available to ecologists (Farley et al. 2018). While such data offer exciting opportunities for unveiling original patterns and trends, they also raise new challenges regarding how to extract relevant information and actually improve our knowledge of complex ecological systems, beyond purely descriptive correlations (Dietze 2017, Farley et al. 2018). In this work, Caumette et al. (2024) develop an original ecoinformatics approach to relate multi-scale environmental factors to the temporal dynamics of a major pest in mango orchards. Their method relies on the recent tree-boosting method GPBoost (Sigrist 2022) to hierarchize the influence of environmental factors of heterogeneous nature (e.g., orchard composition and management; landscape structure; climate) on the emergence date of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. As boosting methods allows the analysis of high-dimensional data, they are particularly adapted to the exploration of such datasets, to uncover unexpected, potentially complex dependencies between ecological dynamics and multiple environmental factors (Farley et al. 2018). In this article, Caumette et al. (2024) make a special effort to guide the reader step by step through their complex analysis pipeline to make it broadly understandable to the average ecologist, which is no small feat. I particularly welcome this commitment, as making new, cutting-edge analytical methods accessible to a large community of science practitioners with varying degrees of statistical or programming expertise is a major challenge for the future of quantitative ecology. The main result of Caumette et al. (2024) is that temperature and humidity conditions both at the local and regional scales are the main predictors of B. dorsalis emergence date, while orchard management practices seem to have relatively little influence. This suggests that favourable climatic conditions may allow the persistence of small populations of B. dorsalis over the dry season, which may then act as a propagule source for early re-infestations. However, as the authors explain, the resulting regression model is not designed for predictive purposes and should not at this stage be used for decision-making in pest management. Its main interest rather resides in identifying potential key factors favoring early infestations of B. dorsalis, and help focusing future experimental field studies on the most relevant levers for integrated pest management in mango orchards. In a wider perspective, this work also provides a convincing proof-of-concept for the use of boosting methods to identify the most influential factors in large, multivariate datasets in a variety of ecological systems. It is also crucial to keep in mind that the current exponential growth in high-throughput environmental data (Lucivero 2020) could quickly come into conflict with the need to reduce the environmental footprint of research (Mariette et al. 2022). In this context, robust and accessible methods for extracting and exploiting all the information available in already existing datasets might prove essential to a sustainable pursuit of science. References Dietze MC. 2017. Ecological Forecasting. Princeton University Press Mariette J, Blanchard O, Berné O, Aumont O, Carrey J, Ligozat A-L, Lellouch E, Roche P-E, Guennebaud G, Thanwerdas J, Bardou P, Salin G, Maigne E, Servan S, Ben-Ari T 2022. An open-source tool to assess the carbon footprint of research. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ac84a4 | Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of *Bactrocera dorsalis* population growth in Senegalese orchards | Cécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier | <p>Implementing integrated pest management programs to limit agricultural pest damage requires an understanding of the interactions between the environmental variability and population demographic processes. However, identifying key environmental ... |  | Demography, Landscape ecology, Statistical ecology | Elodie Vercken | 2023-12-11 17:02:08 | View | |

28 Jun 2024

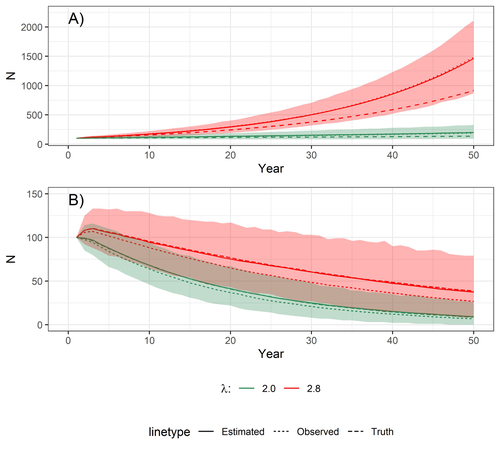

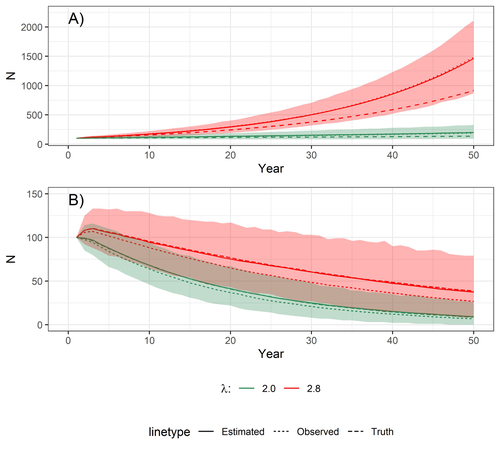

Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity: case study on the arboreal-nesting red kite (Milvus milvus)Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Brady J. Mattsson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.01.569571Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young: you may count too many or too few...Recommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by Steffen Oppel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Steffen Oppel and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most species are hard to observe, and different methods are required to estimate demographic parameters such as the number of young individuals produced (one measure of breeding success) and survival. In the former case, and in particular for birds of prey, it often relies upon direct observations of breeding pairs on their nests. Two problems can then occur, that some young are missed and therefore the breeding success is underestimated (“false negatives”), but it is also possible that because for example of the nest structure or vegetation surrounding the nest, more young birds than in fact are present are counted (“false positives”). Sollmann et al. (2024) address this problem by using data where the truth is known as each nest was also accessed after climbing the tree, and a hierarchical model accounting for both undercounts and overcounts. Finally, they assess the impact of this correction on projected population size using simulations. This paper is a solid contribution to the panoply of methods and models that are available for monitoring populations, and has potential applications for many species for which both false positives and false negatives can be a problem. The results on the projected population sizes – showing that for growing populations correcting for bias can lead to large differences in population sizes after a few decades – may seem counterintuitive as population growth rate of long-lived species such as birds of prey is not very sensitive to a change in breeding success (as compared to adult survival). However, one should just be reminded that a small difference in population growth rate may translate to a large difference after many years – for example a growth rate of 1.05 after 50 years mean than population size is multiplied by 11.5, whereas a growth of 1.03 after 50 years mean a multiplication by 4.4, more than twice less individuals. Small differences may matter a lot if they are sustained, and a key aspect of management is to ensure that they are. Of course, management actions having an impact on survival may be more effective, but they might be harder to achieve than for example ensuring that birds of prey breed successfully. References Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Mattsson Brady J. 2024. Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity. bioRxiv, v. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.01.569571

| Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity: case study on the arboreal-nesting red kite (*Milvus milvus*) | Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Brady J. Mattsson | <p style="text-align: justify;">Counting the number of young in a brood from a distance is common practice, for example in tree-nesting birds. These counts can, however, suffer from over and undercounting, which can lead to biased estimates of fec... |  | Demography, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2023-12-11 08:52:22 | View | |

18 Mar 2019

Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasiteAmalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2592114Limited dispersal in a vector on territorial hostsRecommended by Adele Mennerat based on reviews by Shelly Lachish and 1 anonymous reviewerParasitism requires parasites and hosts to meet and is therefore conditioned by their respective dispersal abilities. While dispersal has been studied in a number of wild vertebrates (including in relation to infection risk), we still have poor knowledge of the movements of their parasites. Yet we know that many parasites, and in particular vectors transmitting pathogens from host to host, possess the ability to move actively during at least part of their lives. References | Evaluating functional dispersal and its eco-epidemiological implications in a nest ectoparasite | Amalia Rataud, Marlène Dupraz, Céline Toty, Thomas Blanchon, Marion Vittecoq, Rémi Choquet, Karen D. McCoy | <p>Functional dispersal (between-site movement, with or without subsequent reproduction) is a key trait acting on the ecological and evolutionary trajectories of a species, with potential cascading effects on other members of the local community. ... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Epidemiology, Parasitology, Population ecology | Adele Mennerat | 2018-11-05 11:44:58 | View | |

12 Jan 2024

Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonisAlexius Folk, Adele Mennerat https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695Marking invertebrates using RFID tagsRecommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Simon Blanchet and 1 anonymous reviewer

Guiding and monitoring the efficiency of conservation efforts needs robust scientific background information, of which one key element is estimating wildlife abundance and its spatial and temporal variation. As raw counts are by nature incomplete counts of a population, correcting for detectability is required (Clobert, 1995; Turlure et al., 2018). This can be done with Capture-Mark-Recapture protocols (Iijima, 2020). Techniques for marking individuals are diverse, e.g. writing on butterfly wings, banding birds, or using natural specific patterns in the individual’s body such as leopard fur or whale tail. Advancement in technology opens new opportunities for developing marking techniques, including strategies to limit mark identification errors (Burchill & Pavlic, 2019), and for using active marks that can transmit data remotely or be read automatically. The details of such methodological developments frequently remain unpublished, the method being briefly described in studies that use it. For a few years, there has been however a renewed interest in proper publishing of methods for ecology and evolution. This study by Folk & Mennerat (2023) fits in this context, offering a nice example of detailed description and testing of a method to mark salmon ectoparasites using RFID tags. Such tags are extremely small, yet easy to use, even with automatic recording procedure. The study provides a very good basis protocol that should help researchers working for small species, in particular invertebrates. The study is complemented by a video illustrating the placement of the tag so the reader who would like to replicate the procedure can get a very precise idea of it. References Burchill, A. T., & Pavlic, T. P. (2019). Dude, where’s my mark? Creating robust animal identification schemes informed by communication theory. Animal Behaviour, 154, 203–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2019.05.013 Clobert, J. (1995). Capture-recapture and evolutionary ecology: A difficult wedding ? Journal of Applied Statistics, 22(5–6), 989–1008. Folk, A., & Mennerat, A. (2023). Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse Lepeophtheirus salmonis (p. 2023.08.31.555695). bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.31.555695 Iijima, H. (2020). A Review of Wildlife Abundance Estimation Models: Comparison of Models for Correct Application. Mammal Study, 45(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.3106/ms2019-0082 Turlure, C., Pe’er, G., Baguette, M., & Schtickzelle, N. (2018). A simplified mark–release–recapture protocol to improve the cost effectiveness of repeated population size quantification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(3), 645–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12900 | Methods for tagging an ectoparasite, the salmon louse *Lepeophtheirus salmonis* | Alexius Folk, Adele Mennerat | <p style="text-align: justify;">Monitoring individuals within populations is a cornerstone in evolutionary ecology, yet individual tracking of invertebrates and particularly parasitic organisms remains rare. To address this gap, we describe here a... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Marine ecology, Parasitology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | 2023-09-04 15:25:08 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle