Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Apr 2023

Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical floraJulien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127Pollination-herbivory by weevils claiming for recognition: the Cinderella among pollinatorsRecommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Susan Kirmse, Carlos Eduardo Nunes and 2 anonymous reviewersSince Charles Darwin times, and probably earlier, naturalists have been eager to report the rarest pollinators being discovered, and this still happens even in recent times; e.g., increased evidence of lizards, cockroaches, crickets or earwigs as pollinators (Suetsugu 2018, Komamura et al. 2021, de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023), shifts to invasive animals as pollinators, including passerine birds and rats (Pattemore & Wilcove 2012), new amazing cases of mimicry in pollination, such as “bleeding” flowers that mimic wounded insects (Heiduk et al., 2023) or even the possibility that a tree frog is reported for the first time as a pollinator (de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023). This is in part due to a natural curiosity of humans about rarity, which pervades into scientific insight (Gaston 1994). Among pollinators, the apparent rarity of some interaction types is sometimes a symptom of a lack of enough inquiry. This seems to be the case of weevil pollination, given that these insects are widely recognized as herbivores, particularly those that use plant parts to nurse their breed and never were thought they could act also as mutualists, pollinating the species they infest. This is known as a case of brood site pollination mutualism (BSPM), which also involves an antagonistic counterpart (herbivory) to which plants should face. This is the focus of the manuscript (Haran et al. 2023) we are recommending here. There is wide treatment of this kind of pollination in textbooks, albeit focused on yucca-yucca moth and fig-fig wasp interactions due to their extreme specialization (Pellmyr 2003, Kjellberg et al. 2005), and more recently accompanied by Caryophyllaceae-moth relationship (Kephart et al. 2006). Here we find a detailed review that shows that the most diverse BSPM, in terms of number of plant and pollinator species involved, is that of weevils in the tropics. The mechanism of BSPM does not involve a unique morphological syndrome, as it is mostly functional and thus highly dependent on insect biology (Fenster & al. 2004), whereas the flower phenotypes are highly divergent among species. Probably, the inconspicuous nature of the interaction, and the overwhelming role of weevils as seed predators, even as pests, are among the causes of the neglection of weevils as pollinators, as it could be in part the case of ants as pollinators (de Vega et al. 2014). The paper by Haran et al (2023) comes to break this point. Thus, the rarity of weevil pollination in former reports is not a consequence of an anecdotical nature of this interaction, even for the BSPM, according to the number of cases the authors are reporting, both in terms of plant and pollinator species involved. This review has a classical narrative format which involves a long text describing the natural history behind the cases. It is timely and fills the gap for this important pollination interaction for biodiversity and also for economic implications for fruit production of some crops. Former reviews have addressed related topics on BSPM but focused on other pollinators, such as those mentioned above. Besides, the review put much effort into the animal side of the interaction, which is not common in the pollination literature. Admittedly, the authors focus on the detailed description of some paradigmatic cases, and thereafter suggest that these can be more frequently reported in the future, based on varied evidence from morphology, natural history, ecology, and distribution of alleged partners. This procedure was common during the development of anthecology, an almost missing term for floral ecology (Baker 1983), relying on accumulative evidence based on detailed observations and experiments on flowers and pollinators. Currently, a quantitative approach based on the tools of macroecological/macroevolutionary analyses is more frequent in reviews. However, this approach requires a high amount of information on the natural history of the partnership, which allows for sound hypothesis testing. By accumulating this information, this approach allows the authors to pose specific questions and hypotheses which can be tested, particularly on the efficiency of the systems and their specialization degree for both the plants and the weevils, apparently higher for the latter. This will guarantee that this paper will be frequently cited by floral ecologists and evolutionary biologists and be included among the plethora of floral syndromes already described, currently based on more explicit functional grounds (Fenster et al. 2004). In part, this is one of the reasons why the sections focused on future prospects is so large in the review. I foresee that this mutualistic/antagonistic relationship will provide excellent study cases for the relative weight of these contrary interactions among the same partners and its relationship with pollination specialization-generalization and patterns of diversification in the plants and/or the weevils. As new studies are coming, it is possible that BSPM by weevils appears more common in non-tropical biogeographical regions. In fact, other BSPM are not so uncommon in other regions (Prieto-Benítez et al. 2017). In the future, it would be desirable an appropriate testing of the actual effect of phylogenetic niche conservatism, using well known and appropriately selected BSPM cases and robust phylogenies of both partners in the mutualism. Phylogenetic niche conservatism is a central assumption by the authors to report as many cases as possible in their review, and for that they used taxonomic relatedness. As sequence data and derived phylogenies for large numbers of vascular plant species are becoming more frequent (Jin & Quian 2022), I would recommend the authors to perform a comparative analysis using this phylogenetic information. At least, they have included information on phylogenetic relatedness of weevils involved in BSPM which allow some inferences on the multiple origins of this interaction. This is a good start to explore the drivers of these multiple origins through the lens of comparative biology. References Baker HG (1983) An Outline of the History of Anthecology, or Pollination Biology. In: L Real (ed). Pollination Biology. Academic Press. de-Oliveira-Nogueira CH, Souza UF, Machado TM, Figueiredo-de-Andrade CA, Mónico AT, Sazima I, Sazima M, Toledo LF (2023). Between fruits, flowers and nectar: The extraordinary diet of the frog Xenohyla truncate. Food Webs 35: e00281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2023.e00281 Fenster CB W, Armbruster S, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD (2004). Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35: 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347 Gaston KJ (1994). What is rarity? In KJ Gaston (ed): Rarity. Population and Community Biology Series, vol 13. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0701-3_1 Haran J, Kergoat GJ, Bruno, de Medeiros AS (2023) Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora. hal. 03780127, version 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127 Heiduk A, Brake I, Shuttleworth A, Johnson SD (2023) ‘Bleeding’ flowers of Ceropegia gerrardii (Apocynaceae-Asclepiadoideae) mimic wounded insects to attract kleptoparasitic fly pollinators. New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18888 Jin, Y., & Qian, H. (2022). V. PhyloMaker2: An updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity, 44(4), 335-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.05.005 Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Hossaert-Mckey M, Rasplus JY (2005). Biology, ecology, and evolution of fig-pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). In: A. Raman et al (eds) Biology, ecology and evolution of gall-inducing arthropods 2, 539-572. Science Publishers, Enfield. Komamura R, Koyama K, Yamauchi T, Konno Y, Gu L (2021). Pollination contribution differs among insects visiting Cardiocrinum cordatum flowers. Forests 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040452 Pattemore DE, Wilcove DS (2012) Invasive rats and recent colonist birds partially compensate for the loss of endemic New Zealand pollinators. Proc. R. Soc. B 279: 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.2036 Pellmyr O (2003) Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 90: 35-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524 Prieto-Benítez S, Yela JL, Giménez-Benavides L (2017) Ten years of progress in the study of Hadena-Caryophyllaceae nursery pollination. A review in light of new Mediterranean data. Flora, 232, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2017.02.004 Suetsugu K (2019) Social wasps, crickets and cockroaches contribute to pollination of the holoparasitic plant Mitrastemon yamamotoi (Mitrastemonaceae) in southern Japan. Plant Biology 21 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12889 | Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora | Julien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros | <p style="text-align: justify;">In tropical environments, and especially tropical rainforests, a major part of pollination services is provided by diverse insect lineages. Unbeknownst to most, beetles, and more specifically hyperdiverse weevils (C... | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Pollination, Tropical ecology | Juan Arroyo | 2022-09-28 11:54:37 | View | ||

07 Aug 2019

Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species?Corina Logan, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Kelsey McCune, Dieter Lukas http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexforaging.htmlUnderstanding geographic range expansions in human-dominated landscapes: does behavioral flexibility modulate flexibility in foraging and social behavior?Recommended by Julia Astegiano and Esther Sebastián González and Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Pizza Ka Yee Chow and Esther Sebastián González

Which biological traits modulate species distribution has historically been and still is one of the core questions of the macroecology and biogeography agenda [1, 2]. As most of the Earth surface has been modified by human activities [3] understanding the strategies that allow species to inhabit human-dominated landscapes will be key to explain species geographic distribution in the Anthropocene. In this vein, Logan et al. [4] are working on a long-term and integrative project aimed to investigate how great-tailed grackles rapidly expanded their geographic range into North America [4]. Particularly, they want to determine which is the role of behavioral flexibility, i.e. an individual’s ability to modify its behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience [5], in rapid geographic range expansions. The authors are already working in a set of complementary questions described in pre-registrations that have already been recommended at PCI Ecology: (1) Do individuals with greater behavioral flexibility rely more on causal cognition [6]? (2) Which are the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility [7]? (3) Does the manipulation of behavioral flexibility affect exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity [8]? (4) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility [9]? References [1] Gaston K. J. (2003) The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. | Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? | Corina Logan, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Kelsey McCune, Dieter Lukas | This is one of the first studies planned for our long-term research on the role of behavioral flexibility in rapid geographic range expansions. Project background: Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change ba... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Julia Astegiano | 2018-10-23 00:47:03 | View | ||

20 Feb 2024

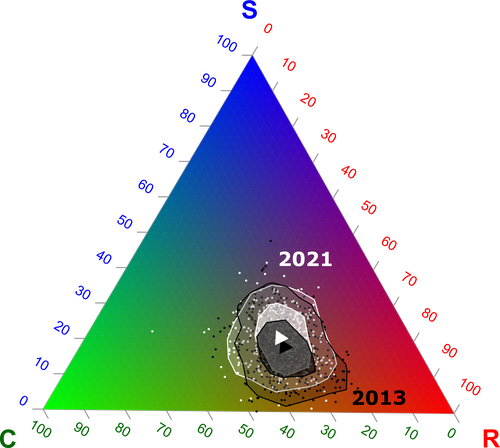

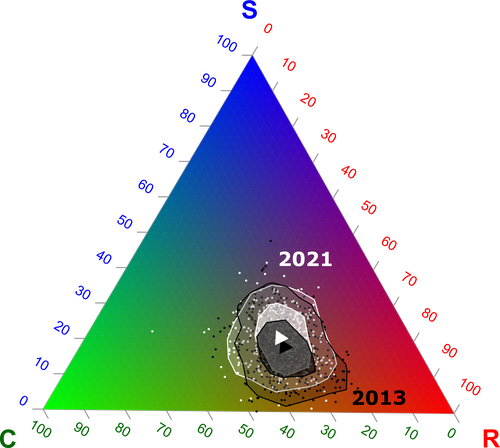

Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practicesIsis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956Unravelling plant diversity in agricultural field margins in France: plant species better adapted to climate change need other agricultures to persistRecommended by Julia Astegiano based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Clelia Sirami and Diego Gurvich

Agricultural field margin plants, often referred to as “spontaneous” species, are key for the stabilization of several social-ecological processes related to crop production such as pollination or pest control (Tamburini et al. 2020). Because of its beneficial function, increasing the diversity of field margin flora becomes as important as crop diversity in process-based agricultures such as agroecology. Contrary, supply-dependent intensive agricultures produce monocultures and homogenized environments that might benefit their productivity, which generally includes the control or elimination of the field margin flora (Emmerson et al. 2016, Aligner 2018). Considering that different agricultural practices are produced by (and produce) different territories (Moore 2020) and that they are also been shaped by current climate change, we urgently need to understand how agricultural intensification constrains the potential of territories to develop agriculture more resilient to such change (Altieri et al., 2015). Thus, studies unraveling how agricultural practices' effects on agricultural field margin flora interact with those of climate change is of main importance, as plant strategies better adapted to such social-ecological processes may differ. References Alignier, A., 2018. Two decades of change in a field margin vegetation metacommunity as a result of field margin structure and management practice changes. Agric., Ecosyst. & Environ., 251, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.013 Altieri, M.A., Nicholls, C.I., Henao, A., Lana, M.A., 2015. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 869–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0285-2 Emmerson, M., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Batary, P., Berendse, F., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Guerrero, I., Bommarco, R., Eggers, S., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Weisser, W., Clement, L. & Bengtsson, J. (2016). How agricultural intensification affects biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Adv. Ecol. Res. 55, 43-97. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2016.08.005 Grime, J. P., 1977. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. The American Naturalist, 111(982), 1169–1194. https://doi.org/10.1086/283244 Grime, J. P., 1988. The C-S-R model of primary plant strategies—Origins, implications and tests. In L. D. Gottlieb & S. K. Jain, Plant Evolutionary Biology (pp. 371–393). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1207-6_14 Moore, J., 2020. El capitalismo en la trama de la vida (Capitalism in The Web of Life). Traficantes de sueños, Madrid, Spain. Poinas, I., Fried, G., Henckel, L., & Meynard, C. N., 2023. Agricultural drivers of field margin plant communities are scale-dependent. Bas. App. Ecol. 72, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2023.08.003 Poinas, I., Meynard, C. N., Fried, G., 2024. Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices, bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.03.530956 Tamburini, G., Bommarco, R., Wanger, T.C., Kremen, C., Van Der Heijden, M.G., Liebman, M., Hallin, S., 2020. Agricultural diversification promotes multiple ecosystem services without compromising yield. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba1715. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1715 | Functional trade-offs: exploring the temporal response of field margin plant communities to climate change and agricultural practices | Isis Poinas, Christine N Meynard, Guillaume Fried | <p style="text-align: justify;">Over the past decades, agricultural intensification and climate change have led to vegetation shifts. However, functional trade-offs linking traits responding to climate and farming practices are rarely analyzed, es... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Climate change, Community ecology | Julia Astegiano | 2023-03-04 15:40:35 | View | |

12 May 2020

On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendationsDavid Murray-Stoker https://doi.org/10.1101/611939A stronger statistical test of stream restoration experimentsRecommended by Karl Cottenie based on reviews by Eric Harvey and Mariana Perez RochaThe metacommunity framework acknowledges that local sites are connected to other sites through dispersal, and that these connectivity patterns can influence local dynamics [1]. This framework is slowly moving from a framework that guides fundamental research to being actively applied in for instance a conservation context (e.g. [2]). Swan and Brown [3,4] analyzed the results of a suite of experimental manipulations in headwater and mainstem streams on invertebrate community structure in the context of the metacommunity concept. This was an important contribution to conservation ecology. References [1] Leibold, M. A., Holyoak, M., Mouquet, N. et al. (2004). The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi‐scale community ecology. Ecology letters, 7(7), 601-613. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x | On the efficacy of restoration in stream networks: comments, critiques, and prospective recommendations | David Murray-Stoker | <p>Swan and Brown (2017) recently addressed the effects of restoration on stream communities under the meta-community framework. Using a combination of headwater and mainstem streams, Swan and Brown (2017) evaluated how position within a stream ne... |  | Community ecology, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Karl Cottenie | 2019-09-21 22:12:57 | View | |

01 Apr 2019

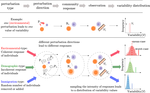

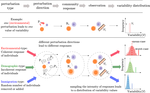

The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patternsJean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman https://doi.org/10.1101/431296Diversity-Stability and the Structure of PerturbationsRecommended by Kevin Cazelles and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer

In his 1972 paper “Will a Large Complex System Be Stable?” [1], May challenges the idea that large communities are more stable than small ones. This was the beginning of a fundamental debate that still structures an entire research area in ecology: the diversity-stability debate [2]. The most salient strength of May’s work was to use a mathematical argument to refute an idea based on the observations that simple communities are less stable than large ones. Using the formalism of dynamical systems and a major results on the distribution of the eigen values for random matrices, May demonstrated that the addition of random interactions destabilizes ecological communities and thus, rich communities with a higher number of interactions should be less stable. But May also noted that his mathematical argument holds true only if ecological interactions are randomly distributed and thus concluded that this must not be true! This is how the contradiction between mathematics and empirical observations led to new developments in the study of ecological networks. References [1] May, Robert M (1972). Will a Large Complex System Be Stable? Nature 238, 413–414. doi: 10.1038/238413a0 | The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patterns | Jean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman | <p>Empirical knowledge of ecosystem stability and diversity-stability relationships is mostly based on the analysis of temporal variability of population and ecosystem properties. Variability, however, often depends on external factors that act as... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Kevin Cazelles | 2018-10-02 14:01:03 | View | |

06 Jan 2021

Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech populationCathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio https://doi.org/10.1101/645747The complexity of predicting mortality in treesRecommended by Lucía DeSoto based on reviews by Lisa Hülsmann and 2 anonymous reviewersOne of the main issues of forest ecosystems is rising tree mortality as a result of extreme weather events (Franklin et al., 1987). Eventually, tree mortality reduces forest biomass (Allen et al., 2010), although its effect on forest ecosystem fluxes seems not lasting too long (Anderegg et al., 2016). This controversy about the negative consequences of tree mortality is joined to the debate about the drivers triggering and the mechanisms accelerating tree decline. For instance, there is still room for discussion about carbon starvation or hydraulic failure determining the decay processes (Sevanto et al., 2014) or about the importance of mortality sources (Reichstein et al., 2013). Therefore, understanding and predicting tree mortality has become one of the challenges for forest ecologists in the last decade, doubling the rate of articles published on the topic (*). Although predicting the responses of ecosystems to environmental change based on the traits of species may seem a simplistic conception of ecosystem functioning (Sutherland et al., 2013), identifying those traits that are involved in the proneness of a tree to die would help to predict how forests will respond to climate threatens. (*) Number (and percentage) of articles found in Web of Sciences after searching (December the 10th, 2020) “tree mortality”: from 163 (0.006%) in 2010 to 412 (0.013%) in 2020. References Allen et al. (2010). A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. Forest ecology and management, 259(4), 660-684. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2009.09.001 | Comparing statistical and mechanistic models to identify the drivers of mortality within a rear-edge beech population | Cathleen Petit-Cailleux, Hendrik Davi, François Lefevre, Christophe Hurson, Joseph Garrigue, Jean-André Magdalou, Elodie Magnanou and Sylvie Oddou-Muratorio | <p>Since several studies have been reporting an increase in the decline of forests, a major issue in ecology is to better understand and predict tree mortality. The interactions between the different factors and the physiological processes giving ... |  | Climate change, Physiology, Population ecology | Lucía DeSoto | 2019-05-24 11:37:38 | View | |

14 Dec 2018

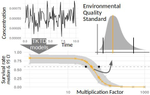

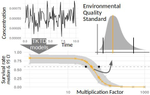

Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics modelsVirgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles https://doi.org/10.1101/356469Addressing uncertainty in Environmental Risk Assessment using mechanistic toxicological models coupled with Bayesian inferenceRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Andreas Focks and 2 anonymous reviewersEnvironmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a strategic conceptual framework to characterize the nature and magnitude of risks, to humans and biodiversity, of the release of chemical contaminants in the environment. Several measures have been suggested to enhance the science and application of ERA, including the identification and acknowledgment of uncertainties that potentially influence the outcome of risk assessments, and the appropriate consideration of temporal scale and its linkage to assessment endpoints [1]. References [1] Dale, V. H., Biddinger, G. R., Newman, M. C., Oris, J. T., Suter, G. W., Thompson, T., ... & Chapman, P. M. (2008). Enhancing the ecological risk assessment process. Integrated environmental assessment and management, 4(3), 306-313. doi: 10.1897/IEAM_2007-066.1 | Recommendations to address uncertainties in environmental risk assessment using toxicokinetics-toxicodynamics models | Virgile Baudrot and Sandrine Charles | <p>Providing reliable environmental quality standards (EQS) is a challenging issue for environmental risk assessment (ERA). These EQS are derived from toxicity endpoints estimated from dose-response models to identify and characterize the environm... |  | Chemical ecology, Ecotoxicology, Experimental ecology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2018-06-27 21:33:30 | View | |

13 Jul 2023

Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predatorsLoïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552Indirect effects of parasitism include increased profitability of prey to optimal foragersRecommended by Luis Schiesari based on reviews by Thierry DE MEEUS and Eglantine Mathieu-BégnéEven though all living organisms are, at the same time, involved in host-parasite interactions and embedded in complex food webs, the indirect effects of parasitism are only beginning to be unveiled. Prosnier et al. investigated the direct and indirect effects of parasitism making use of a very interesting biological system comprising the freshwater zooplankton Daphnia magna and its highly specific parasite, the iridovirus DIV-1 (Daphnia-iridescent virus 1). Daphnia are typically semitransparent, but once infected develop a white phenotype with a characteristic iridescent shine due to the enlargement of white fat cells. In a combination of infection trials and comparison of white and non-white phenotypes collected in natural ponds, the authors demonstrated increased mortality and reduced lifetime fitness in infected Daphnia. Furthermore, white phenotypes had lower mobility, increased reflectance, larger body sizes and higher protein content than non-white phenotypes. As a consequence, total energy content was effectively doubled in white Daphnia when compared to non-white broodless Daphnia. Next the authors conducted foraging trials with Daphnia predators Notonecta (the backswimmer) and Phoxinus (the European minnow). Focusing on Notonecta, unchanged search time and increased handling time were more than compensated by the increased energy content of white Daphnia. White Daphnia were 24% more profitable and consistently preferred by Notonecta, as the optimal foraging theory would predict. The authors argue that menu decisions of optimal foragers in the field might be different, however, as the prevalence – and therefore availability - of white phenotypes in natural populations is very low. The study therefore contributes to our understanding of the trophic context of parasitism. One shortcoming of the study is that the authors rely exclusively on phenotypic signs for determining infection. On their side, DIV-1 is currently known to be highly specific to Daphnia, their study site is well within DIV-1 distributional range, and the symptoms of infection are very conspicuous. Furthermore, the infection trial – in which non-white Daphnia were exposed to white Daphnia homogenates - effectively caused several lethal and sublethal effects associated with DIV-1 infection, including iridescence. However, the infection trial also demonstrated that part of the exposed individuals developed intermediate traits while still keeping the non-white, non-iridescent phenotype. Thus, there may be more subtleties to the association of DIV-1 infection of Daphnia with ecological and evolutionary consequences, such as costs to resistance or covert infection, that the authors acknowledge, and that would be benefitted by coupling experimental and observational studies with the determination of actual infection and viral loads. References Prosnier L., N. Loeuille, F.D. Hulot, D. Renault, C. Piscart, B. Bicocchi, M, Deparis, M. Lam, & V. Médoc. (2023). Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators. BioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.08.479552 | Parasites make hosts more profitable but less available to predators | Loïc Prosnier, Nicolas Loeuille, Florence D. Hulot, David Renault, Christophe Piscart, Baptiste Bicocchi, Muriel Deparis, Matthieu Lam, Vincent Médoc | <p>Parasites are omnipresent, and their eco-evolutionary significance has aroused much interest from scientists. Parasites may affect their hosts in many ways by altering host density, vulnerability to predation, and energy content, thus modifying... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Epidemiology, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Life history, Parasitology, Statistical ecology | Luis Schiesari | 2022-05-20 10:15:41 | View | |

18 Dec 2019

Validating morphological condition indices and their relationship with reproductive success in great-tailed gracklesJennifer M. Berens, Corina J. Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Kelsey B. McCune https://github.com/corinalogan/grackles/blob/master/Files/Preregistrations/gcondition.RmdAre condition indices positively related to each other and to fitness?: a test with gracklesRecommended by Marcos Mendez based on reviews by Javier Seoane and Isabel López-RullReproductive succes, as a surrogate of individual fitness, depends both on extrinsic and intrinsic factors [1]. Among the intrinsic factors, resource level or health are considered important potential drivers of fitness but exceedingly difficult to measure directly. Thus, a host of proxies have been suggested, known as condition indices [2]. The question arises whether all condition indices consistently measure the same "inner state" of individuals and whether all of them similarly correlate to individual fitness. In this preregistration, Berens and colleagues aim to answer this question for two common condition indices, fat score and scaled mass index (Fig. 1), using great-tailed grackles as a model system. Although this question is not new, it has not been satisfactorily solved and both reviewers found merit in the attempt to clarify this matter. References [1] Roff, D. A. (2001). Life history evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford. | Validating morphological condition indices and their relationship with reproductive success in great-tailed grackles | Jennifer M. Berens, Corina J. Logan, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Kelsey B. McCune | Morphological variation among individuals has the potential to influence multiple life history characteristics such as dispersal, migration, reproductive fitness, and survival (Wilder, Raubenheimer, and Simpson (2016)). Theoretically, individuals ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology, Demography, Morphometrics, Preregistrations, Zoology | Marcos Mendez | 2019-08-05 20:05:56 | View | ||

16 Oct 2018

Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus)Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4How empirical sciences may improve livestock welfare and help their managementRecommended by Marie Charpentier based on reviews by Alecia CARTER and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding how livestock management is a source of social stress and disturbances for cattle is an important question with potential applications for animal welfare programs and sustainable development. In their article, Sosa and colleagues [1] first propose to evaluate the effects of individual characteristics on dyadic social relationships and on the social dynamics of four groups of cattle. Using network analyses, the authors provide an interesting and complete picture of dyadic interactions among groupmates. Although shown elsewhere, the authors demonstrate that individuals that are close in age and close in rank form stronger dyadic associations than other pairs. Second, the authors take advantage of some transfers of animals between groups -for management purposes- to assess how these transfers affect the social dynamics of groupmates. Their central finding is that the identity of transferred animals is a key-point. In particular, removing offspring strongly destabilizes the social relationships of mothers while adding a bull into a group also profoundly impacts female-female social relationships, as social networks before and after transfer of these key-animals are completely different. In addition, individuals, especially the young ones, that are transferred without familiar conspecifics take more time to socialize with their new group members than individuals transferred with familiar groupmates, generating a potential source of stress. Interestingly, the authors end up their article with some thoughts on the implications of their findings for animal welfare and ethics. This study provides additional evidence that empirical science has a major role to play in providing recommendations regarding societal questions such as livestock management and animal wellbeing. References [1] Sosa, S., Pelé, M., Debergue, E., Kuntz, C., Keller, B., Robic, F., Siegwalt-Baudin, F., Richer, C., Ramos, A., & Sueur C. (2018). Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus). arXiv:1805.11553v4 [q-bio.PE] peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4 | Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus) | Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur | The sociality of cattle facilitates the maintenance of herd cohesion and synchronisation, making these species the ideal choice for domestication as livestock for humans. However, livestock populations are not self-regulated, and farmers transfer ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure | Marie Charpentier | 2018-05-30 14:05:39 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle