Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * ▲ | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Aug 2021

A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm callSamantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5Does the active vocabulary in Great-tailed Grackles supports their range expansion? New study will find outRecommended by Jan Oliver Engler based on reviews by Guillermo Fandos and 2 anonymous reviewersAlarm calls are an important acoustic signal that can decide the life or death of an individual. Many birds are able to vary their alarm calls to provide more accurate information on e.g. urgency or even the type of a threatening predator. According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis, the habitat plays an important role too in how acoustic patterns get transmitted. This is of particular interest for range-expanding species that will face new environmental conditions along the leading edge. One could hypothesize that the alarm call repertoire of a species could increase in newly founded ranges to incorporate new habitats and threats individuals might face. Hence selection for a larger active vocabulary might be beneficial for new colonizers. Using the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a model species, Samantha Bowser from Arizona State University and Maggie MacPherson from Louisiana State University want to find out exactly that. The Great-Tailed Grackle is an appropriate species given its high vocal diversity. Also, the species consists of different subspecies that show range expansions along the northern range edge yet to a varying degree. Using vocal experiments and field recordings the researchers have a high potential to understand more about the acoustic adaptation hypothesis within a range dynamic process. Over the course of this assessment, the authors incorporated the comments made by two reviewers into a strong revision of their research plans. With that being said, the few additional comments made by one of the initial reviewers round up the current stage this interesting research project is in. To this end, I can only fully recommend the revised research plan and am much looking forward to the outcomes from the author’s experiments, modeling, and field data. With the suggestions being made at such an early stage I firmly believe that the final outcome will be highly interesting not only to an ornithological readership but to every ecologist and biogeographer interested in drivers of range dynamic processes. References Bowser, S., MacPherson, M. (2021). A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call. In principle recommendation by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5. Version 3 | A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call | Samantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson | <p>The acoustic adaptation hypothesis posits that animal sounds are influenced by the habitat properties that shape acoustic constraints (Ey and Fischer 2009, Morton 2015, Sueur and Farina 2015).Alarm calls are expected to signal important habitat... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Coexistence, Dispersal & Migration, Habitat selection, Landscape ecology | Jan Oliver Engler | Darius Stiels, Anonymous | 2020-12-01 18:11:02 | View |

10 Oct 2018

Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence dataSamuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea https://doi.org/10.1101/256586Combining epidemiological models with statistical inference can detect parasite interactionsRecommended by Dustin Brisson based on reviews by Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne and 1 anonymous reviewerThere are several important topics in the study of infectious diseases that have not been well explored due to technical difficulties. One such topic is pursued by Alizon et al. in “Modelling coinfections to detect within-host interactions from genotype combination prevalences” [1]. Both theory and several important examples have demonstrated that interactions among co-infecting strains can have outsized impacts on disease outcomes, transmission dynamics, and epidemiology. Unfortunately, empirical data on pathogen interactions and their outcomes is often correlational making results difficult to decipher. References [1] Alizon, S., Murall, C.L., Saulnier, E., & Sofonea, M.T. (2018). Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data. bioRxiv, 256586, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/256586 | Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data | Samuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea | <p>Parasite genetic diversity can provide information on disease transmission dynamics but most methods ignore the exact combinations of genotypes in infections. We introduce and validate a new method that combines explicit epidemiological modelli... |  | Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Statistical ecology | Dustin Brisson | Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne | 2018-02-01 09:23:26 | View |

12 Apr 2023

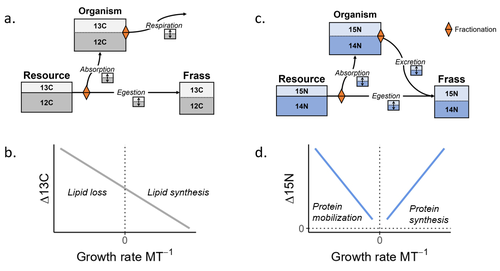

Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larvaSamuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573Refining our understanding how nutritional conditions affect 13C and 15N isotopic fractionation during ontogeny in a herbivorous insectRecommended by Gregor Kalinkat based on reviews by Anton Potapov and 1 anonymous reviewerUsing stable isotope fractionation to disentangle and understand the trophic positions of animals within the food webs they are embedded within has a long tradition in ecology (Post, 2002; Scheu, 2002). Recent years have seen increasing application of the method with several recent reviews summarizing past advancements in this field (e.g. Potapov et al., 2019; Quinby et al., 2020). In their new manuscript, Charberet and colleagues (2023) set out to refine our understanding of the processes that lead to nitrogen and carbon stable isotope fractionation by investigating how herbivorous insect larvae (specifically, the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis) respond to varying nutritional conditions (from starving to ad libitum feeding) in terms of stable isotopes enrichment. Though the underlying mechanisms have been experimentally investigated before in terrestrial invertebrates (e.g. in wolf spiders; Oelbermann & Scheu, 2002), the elegantly designed and adequately replicated experiments by Charberet and colleagues add new insights into this topic. Particularly, the authors provide support for the hypotheses that (A) 15N is disproportionately accumulated under fast growth rates (i.e. when fed ad libitum) and that (B) 13C is accumulated under low growth rates and starvation due to depletion of 13C-poor fat tissues. Applying this knowledge to field samples where feeding conditions are usually not known in detail is not straightforward, but the new findings could still help better interpretation of field data under specific conditions that make starvation for herbivores much more likely (e.g. droughts). Overall this study provides important methodological advancements for a better understanding of plant-herbivore interactions in a changing world. REFERENCES Charberet, S., Maria, A., Siaussat, D., Gounand, I., & Mathieu, J. (2023). Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573 Oelbermann, K., & Scheu, S. (2002). Stable Isotope Enrichment (δ 15N and δ 13C) in a Generalist Predator (Pardosa lugubris, Araneae: Lycosidae): Effects of Prey Quality. Oecologia, 130(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100813 Post, D. M. (2002). Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology, 83(3), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2 Potapov, A. M., Tiunov, A. V., & Scheu, S. (2019). Uncovering trophic positions and food resources of soil animals using bulk natural stable isotope composition. Biological Reviews, 94(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12434 Quinby, B. M., Creighton, J. C., & Flaherty, E. A. (2020). Stable isotope ecology in insects: A review. Ecological Entomology, 45(6), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12934 Scheu, S. (2002). The soil food web: Structure and perspectives. European Journal of Soil Biology, 38(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01117-7 | Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva | Samuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu | <p style="text-align: justify;">Isotopes are widely used in ecology to study food webs and physiology. The fractionation observed between trophic levels in nitrogen and carbon isotopes, explained by isotopic biochemical selectivity, is subject to ... |  | Experimental ecology, Food webs, Physiology | Gregor Kalinkat | 2022-11-16 15:23:31 | View | |

16 Oct 2018

Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus)Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4How empirical sciences may improve livestock welfare and help their managementRecommended by Marie Charpentier based on reviews by Alecia CARTER and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding how livestock management is a source of social stress and disturbances for cattle is an important question with potential applications for animal welfare programs and sustainable development. In their article, Sosa and colleagues [1] first propose to evaluate the effects of individual characteristics on dyadic social relationships and on the social dynamics of four groups of cattle. Using network analyses, the authors provide an interesting and complete picture of dyadic interactions among groupmates. Although shown elsewhere, the authors demonstrate that individuals that are close in age and close in rank form stronger dyadic associations than other pairs. Second, the authors take advantage of some transfers of animals between groups -for management purposes- to assess how these transfers affect the social dynamics of groupmates. Their central finding is that the identity of transferred animals is a key-point. In particular, removing offspring strongly destabilizes the social relationships of mothers while adding a bull into a group also profoundly impacts female-female social relationships, as social networks before and after transfer of these key-animals are completely different. In addition, individuals, especially the young ones, that are transferred without familiar conspecifics take more time to socialize with their new group members than individuals transferred with familiar groupmates, generating a potential source of stress. Interestingly, the authors end up their article with some thoughts on the implications of their findings for animal welfare and ethics. This study provides additional evidence that empirical science has a major role to play in providing recommendations regarding societal questions such as livestock management and animal wellbeing. References [1] Sosa, S., Pelé, M., Debergue, E., Kuntz, C., Keller, B., Robic, F., Siegwalt-Baudin, F., Richer, C., Ramos, A., & Sueur C. (2018). Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus). arXiv:1805.11553v4 [q-bio.PE] peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4 | Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus) | Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur | The sociality of cattle facilitates the maintenance of herd cohesion and synchronisation, making these species the ideal choice for domestication as livestock for humans. However, livestock populations are not self-regulated, and farmers transfer ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure | Marie Charpentier | 2018-05-30 14:05:39 | View | ||

14 Dec 2022

The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore dietSébastien Ibanez, Arnaud Foulquier, Charles Brun, Marie-Pascale Colace, Gabin Piton, Lionel Bernard, Christiane Gallet, Jean-Christophe Clément https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.04.497718Complex interactions between ecosystem productivity and herbivore diets lead to non-predicted effects on nutrient cyclingRecommended by Sébastien Barot based on reviews by Manuel Blouin and Tord Ranheim SveenThe authors present a study typical of the field of belowground-aboveground interactions [1]. This framework has been extremely fruitful since the beginning of 2000s [2]. It has also contributed to bridge the gap between soil ecology and the rest of ecology [3]. The study also pertains to the rich field on the impacts of herbivores on soil functioning [4]. The study more precisely tested during two years the effect on nutrient cycling of the interaction between the type of grassland (along a gradient of biomass productivity) and the diet of the community of insect herbivores (5 treatments manipulating the grasshopper community on 1 m2 plots, with a gradient from no grasshopper to grasshoppers either specialized on forbs or grasses). What seems extremely interesting is that the study is based on a rigorous hypothesis-testing approach. They compare the predictions of two frameworks: (1) The “productivity model” predicts that in productive ecosystems herbivores consume a high percentage of the net primary production thus accelerating nutrient cycling. (2) The “diet model” distinguishes herbivores consuming exploitative plants from those eating conservative plants. The former (later) type of herbivores favours conservative (exploitative) plants therefore decelerating (accelerating) nutrient cycling. Interestingly, the two frameworks have similar predictions (and symmetrically opposite predictions) in two cases out of four combinations between ecosystem productivities and types of diet (see Table 1). An other merit of the study is to combine in a rather comprehensive way all the necessary measurements to test these frameworks in combination: grasshopper diet, soil properties, characteristics of the soil microbial community, plant traits, vegetation survey and plant biomass. The results were in contradiction with the ‘‘diet model’’: microbial properties and nitrogen cycling did not depend on grasshopper diet. The productivity of the grasslands did impact nutrient cycling but not in the direction predicted by the “productivity model”: productive grasslands hosted exploitative plants that depleted N resources in the soil and microbes producing few extracellular enzymes, which led to a lower potential N mineralization and a deceleration of nutrient cycling. Because, the authors stuck to their original hypotheses (that were not confirmed), they were able to discuss in a very relevant way their results and to propose some interpretations, at least partially based on the time scales involved by the productivity and diet models. Beyond all the merits of this article, I think that two issues remain largely open in relation with the dynamics of the studied systems, and would deserve future research efforts. First, on the ‘‘short’’ term (up to several decades), can we predict how the communities of plants, soil microbes, and herbivores interact to drive the dynamics of the ecosystems? Second, at the evolutionary time scale, can we understand and predict the interactions between the evolution of plant, microbe and herbivore strategies and the consequences for the functioning of the grasslands? The two issues are difficult because of the multiple feedbacks involved. One way to go further would be to complement the empirical approach with models along existing research avenues [5, 6]. References [1] Ibanez S, Foulquier A, Brun C, Colace M-P, Piton G, Bernard L, Gallet C, Clément J-C (2022) The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore diet. bioRxiv, 2022.07.04.497718, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.04.497718 [2] Hooper, D. U., Bignell, D. E., Brown, V. K., Brussaard, L., Dangerfield, J. M., Wall, D. H., Wardle, D. A., Coleman, D. C., Giller, K. E., Lavelle, P., Van der Putten, W. H., De Ruiter, P. C., et al. 2000. Interactions between aboveground and belowground biodiversity in terretrial ecosystems: patterns, mechanisms, and feedbacks. BioScience, 50, 1049-1061. https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[1049:IBAABB]2.0.CO;2 [3] Barot, S., Blouin, M., Fontaine, S., Jouquet, P., Lata, J.-C., and Mathieu, J. 2007. A tale of four stories: soil ecology, theory, evolution and the publication system. PLoS ONE, 2, e1248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001248 [4] Bardgett, R. D., and Wardle, D. A. 2003. Herbivore-mediated linkages between aboveground and belowground communities. Ecology, 84, 2258-2268. https://doi.org/10.1890/02-0274 [5] Barot, S., Bornhofen, S., Loeuille, N., Perveen, N., Shahzad, T., and Fontaine, S. 2014. Nutrient enrichment and local competition influence the evolution of plant mineralization strategy, a modelling approach. J. Ecol., 102, 357-366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12200 [6] Schweitzer, J. A., Juric, I., van de Voorde, T. F. J., Clay, K., van der Putten, W. H., Bailey, J. K., and Fox, C. 2014. Are there evolutionary consequences of plant-soil feedbacks along soil gradients? Func. Ecol., 28, 55-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12201

| The contrasted impacts of grasshoppers on soil microbial activities in function of primary production and herbivore diet | Sébastien Ibanez, Arnaud Foulquier, Charles Brun, Marie-Pascale Colace, Gabin Piton, Lionel Bernard, Christiane Gallet, Jean-Christophe Clément | <p style="text-align: justify;">Herbivory can have contrasted impacts on soil microbes and nutrient cycling, which has stimulated the development of conceptual frameworks exploring the links between below- and aboveground processes. The "productiv... | Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory, Soil ecology, Terrestrial ecology | Sébastien Barot | 2022-07-14 09:06:13 | View | ||

19 Feb 2020

Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical treeSébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret https://doi.org/10.1101/351197Growth trajectories, better than organ-level functional traits, reveal intraspecific response to environmental variationRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz based on reviews by Georges Kunstler and François Munoz

Functional traits are “morpho-physio-phenological traits which impact fitness indirectly via their effects on growth, reproduction and survival” [1]. Most functional traits are defined at organ level, e.g. for leaves, roots and stems, and reflect key aspects of resource acquisition and resource use by organisms for their development and reproduction [2]. More rarely, some functional traits can be related to spatial development, such as vegetative height and lateral spread in plants. References [1] Violle, C., Navas, M. L., Vile, D., Kazakou, E., Fortunel, C., Hummel, I., & Garnier, E. (2007). Let the concept of trait be functional!. Oikos, 116(5), 882-892. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15559.x | Soil variation response is mediated by growth trajectories rather than functional traits in a widespread pioneer Neotropical tree | Sébastien Levionnois, Niklas Tysklind, Eric Nicolini, Bruno Ferry, Valérie Troispoux, Gilles Le Moguedec, Hélène Morel, Clément Stahl, Sabrina Coste, Henri Caron, Patrick Heuret | <p style="text-align: justify;">1- Trait-environment relationships have been described at the community level across tree species. However, whether interspecific trait-environment relationships are consistent at the intraspecific level is yet unkn... |  | Botany, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Habitat selection, Ontogeny, Tropical ecology | François Munoz | 2018-06-21 17:13:17 | View | |

12 Jan 2022

No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria MosquitoesSerge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542The search for sex pheromones in malaria mosquitoesRecommended by Niels Verhulst based on reviews by Marcelo Lorenzo and 1 anonymous reviewerPheromones are used by many insects to find the opposite sex for mating. Especially for nocturnal mosquitoes it seems logical that such pheromones exist as they can only partly rely on visual cues when flying at night. The males of many mosquito species form swarms and conspecific females fly into these swarms to mate. The two sibling species of malaria mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii coexist and both form swarms consisting of only one species. Although hybrids can be produced, these hybrids are rarely found in nature. In the study presented by Poda and colleagues (2022) it was tested if long-range sex pheromones exist in these two mosquito sibling species. In a previous study by Mozūraites et al. (2020), five compounds (acetoin, sulcatone, octanal, nonanal and decanal) were identified that induced male swarming and increase mating success. Interestingly these compounds are frequently found in nature and have been shown to play a role in sugar feeding or host finding of An. gambiae. In the recommended study performed by Poda et al. (2022) no evidence of long-range sex pheromones in A. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii was found. The discrepancy between the two studies is difficult to explain but some of the methods varied between studies. Mozūraites et al. (2020) for example, collected odours from mosquitoes in small 1l glass bottles, where swarming is questionable, while in the study of Poda et al. (2022) 50 x 40 x 40 cm cages were used and swarming observed, although most swarms are normally larger. On the other hand, some of the analytical techniques used in the Mozūraites et al. (2020) study were more sensitive while others were more sensitive in the Poda et al. (2022) study. Because it is difficult to prove that something does not exist, the authors nicely indicate that “an absence of evidence is not an evidence of absence” (Poda et al., 2022). Nevertheless, recently colonized species were tested in large cage setups where swarming was observed and various methods were used to try to detect sex pheromones. No attraction to the volatile blend from male swarms was detected in an olfactometer, no antenna-electrophysiological response of females to male swarm volatile compounds was detected and no specific male swarm volatile was identified. This study will open the discussion again if (sex) pheromones play a role in swarming and mating of malaria mosquitoes. Future studies should focus on sensitive real-time volatile analysis in mating swarms in large cages or field settings. In comparison to moths for example that are very sensitive to very specific pheromones and attract from a large distance, such a long-range specific pheromone does not seem to exist in these mosquito species. Acoustic and visual cues have been shown to be involved in mating (Diabate et al., 2003; Gibson and Russell, 2006) and especially at long distances, visual cues are probably important for the detection of these swarms. References Diabate A, Baldet T, Brengues C, Kengne P, Dabire KR, Simard F, Chandre F, Hougard JM, Hemingway J, Ouedraogo JB, Fontenille D (2003) Natural swarming behaviour of the molecular M form of Anopheles gambiae. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97, 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80110-4 Gibson G, Russell I (2006) Flying in Tune: Sexual Recognition in Mosquitoes. Current Biology, 16, 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.053 Mozūraitis, R., Hajkazemian, M., Zawada, J.W., Szymczak, J., Pålsson, K., Sekar, V., Biryukova, I., Friedländer, M.R., Koekemoer, L.L., Baird, J.K., Borg-Karlson, A.-K., Emami, S.N. (2020) Male swarming aggregation pheromones increase female attraction and mating success among multiple African malaria vector mosquito species. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1264-9 Poda, S.B., Buatois, B., Lapeyre, B., Dormont, L., Diabate, A., Gnankine, O., Dabire, R.K., Roux, O. (2022) No evidence for long-range male sex pheromones in two malaria mosquitoes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.05.187542, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542 | No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria Mosquitoes | Serge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Cues involved in mate seeking and recognition prevent hybridization and can be involved in speciation processes. In malaria mosquitoes, females of the two sibling species <em>Anopheles gambiae</em> s.s. and <em>An. ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Chemical ecology | Niels Verhulst | 2021-04-26 12:28:36 | View | |

13 Mar 2021

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalSevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6behDispersal: from “neutral” to a state- and context-dependent viewRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTraditionally, dispersal has often been seen as “random” or “neutral” as Lowe & McPeek (2014) have put it. This simplistic view is likely due to dispersal being intrinsically difficult to measure empirically as well as “random” dispersal being a convenient simplifying assumption in theoretical work. Clobert et al. (2009), and many others, have highlighted how misleading this assumption is. Rather, dispersal seems to be usually a complex reaction norm, depending both on internal as well as external factors. One such internal factor is the sex of the dispersing individual. A recent review of the theoretical literature (Li & Kokko 2019) shows that while ideas explaining sex-biased dispersal go back over 40 years this state-dependency of dispersal is far from comprehensively understood. Sevchik et al. (2021) tackle this challenge empirically in a bird species, the great-tailed grackle. In contrast to most bird species, where females disperse more than males, the authors report genetic evidence indicating male-biased dispersal. The authors argue that this difference can be explained by the great-tailed grackle’s social and mating-system. Dispersal is a central life-history trait (Bonte & Dahirel 2017) with major consequences for ecological and evolutionary processes and patterns. Therefore, studies like Sevchik et al. (2021) are valuable contributions for advancing our understanding of spatial ecology and evolution. Importantly, Sevchik et al. also lead to way to a more open and reproducible science of ecology and evolution. The authors are among the pioneers of preregistering research in their field and their way of doing research should serve as a model for others. References Bonte, D. & Dahirel, M. (2017) Dispersal: a central and independent trait in life history. Oikos 126: 472-479. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03801 Clobert, J., Le Galliard, J. F., Cote, J., Meylan, S. & Massot, M. (2009) Informed dispersal, heterogeneity in animal dispersal syndromes and the dynamics of spatially structured populations. Ecol. Lett.: 12, 197-209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01267.x Li, X.-Y. & Kokko, H. (2019) Sex-biased dispersal: a review of the theory. Biol. Rev. 94: 721-736. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12475 Lowe, W. H. & McPeek, M. A. (2014) Is dispersal neutral? Trends Ecol. Evol. 29: 444-450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.05.009 Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. & Lukas, D. (2021) Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. EcoEvoRxiv, osf.io/t6beh, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6beh | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D | <p>In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain closer to the place they hatched for their entire lives. Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have focused on the resource-defense ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-08-24 17:53:06 | View | |

24 Mar 2023

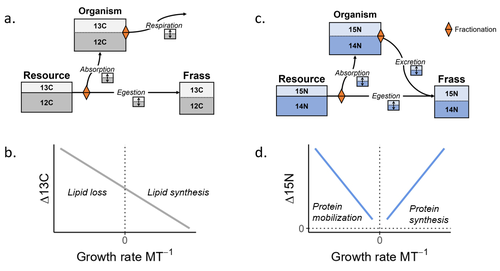

Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imageryShinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59DReview of machine learning uses for the analysis of images on wildlifeRecommended by Olivier Gimenez based on reviews by Falk Huettmann and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the field of ecology, there is a growing interest in machine (including deep) learning for processing and automatizing repetitive analyses on large amounts of images collected from camera traps, drones and smartphones, among others. These analyses include species or individual recognition and classification, counting or tracking individuals, detecting and classifying behavior. By saving countless times of manual work and tapping into massive amounts of data that keep accumulating with technological advances, machine learning is becoming an essential tool for ecologists. We refer to recent papers for more details on machine learning for ecology and evolution (Besson et al. 2022, Borowiec et al. 2022, Christin et al. 2019, Goodwin et al. 2022, Lamba et al. 2019, Nazir & Kaleem 2021, Perry et al. 2022, Picher & Hartig 2023, Tuia et al. 2022, Wäldchen & Mäder 2018). In their paper, Nakagawa et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of the literature on machine learning for wildlife imagery. Interestingly, the authors used a method unfamiliar to ecologists but well-established in medicine called rapid review, which has the advantage of being quickly completed compared to a fully comprehensive systematic review while being representative (Lagisz et al., 2022). Through a rigorous examination of more than 200 articles, the authors identified trends and gaps, and provided suggestions for future work. Listing all their findings would be counterproductive (you’d better read the paper), and I will focus on a few results that I have found striking, fully assuming a biased reading of the paper. First, Nakagawa et al. (2023) found that most articles used neural networks to analyze images, in general through collaboration with computer scientists. A challenge here is probably to think of teaching computer vision to the generations of ecologists to come (Cole et al. 2023). Second, the images were dominantly collected from camera traps, with an increase in the use of aerial images from drones/aircrafts that raise specific challenges. Third, the species concerned were mostly mammals and birds, suggesting that future applications should aim to mitigate this taxonomic bias, by including, e.g., invertebrate species. Fourth, most papers were written by authors affiliated with three countries (Australia, China, and the USA) while India and African countries provided lots of images, likely an example of scientific colonialism which should be tackled by e.g., capacity building and the involvement of local collaborators. Last, few studies shared their code and data, which obviously impedes reproducibility. Hopefully, with the journals’ policy of mandatory sharing of codes and data, this trend will be reversed. REFERENCES Besson M, Alison J, Bjerge K, Gorochowski TE, Høye TT, Jucker T, Mann HMR, Clements CF (2022) Towards the fully automated monitoring of ecological communities. Ecology Letters, 25, 2753–2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14123 Borowiec ML, Dikow RB, Frandsen PB, McKeeken A, Valentini G, White AE (2022) Deep learning as a tool for ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1640–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13901 Christin S, Hervet É, Lecomte N (2019) Applications for deep learning in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13256 Cole E, Stathatos S, Lütjens B, Sharma T, Kay J, Parham J, Kellenberger B, Beery S (2023) Teaching Computer Vision for Ecology. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.02211 Goodwin M, Halvorsen KT, Jiao L, Knausgård KM, Martin AH, Moyano M, Oomen RA, Rasmussen JH, Sørdalen TK, Thorbjørnsen SH (2022) Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: overview, applications, and outlook†. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255 Lagisz M, Vasilakopoulou K, Bridge C, Santamouris M, Nakagawa S (2022) Rapid systematic reviews for synthesizing research on built environment. Environmental Development, 43, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100730 Lamba A, Cassey P, Segaran RR, Koh LP (2019) Deep learning for environmental conservation. Current Biology, 29, R977–R982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.016 Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Francis R, Tam J, Li X, Elphinstone A, Jordan N, O’Brien J, Pitcher B, Sluys MV, Sowmya A, Kingsford R (2023) Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59D Nazir S, Kaleem M (2021) Advances in image acquisition and processing technologies transforming animal ecological studies. Ecological Informatics, 61, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101212 Perry GLW, Seidl R, Bellvé AM, Rammer W (2022) An Outlook for Deep Learning in Ecosystem Science. Ecosystems, 25, 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y Pichler M, Hartig F Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14061 Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, Risse B, Mathis A, Mathis MW, van Langevelde F, Burghardt T, Kays R, Klinck H, Wikelski M, Couzin ID, van Horn G, Crofoot MC, Stewart CV, Berger-Wolf T (2022) Perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. Nature Communications, 13, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27980-y Wäldchen J, Mäder P (2018) Machine learning for image-based species identification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13075 | Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery | Shinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford | <p>1. Machine (especially deep) learning algorithms are changing the way wildlife imagery is processed. They dramatically speed up the time to detect, count, classify animals and their behaviours. Yet, we currently have a very few systematic liter... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology | Olivier Gimenez | Anonymous | 2022-10-31 22:05:46 | View |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle