Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades

Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne

https://doi.org/10.1101/722140

Tell me what you’ve eaten, I’ll tell you how much you’ll eat (and be eaten)

Recommended by Sara Magalhães and Raul Costa-Pereira based on reviews by Bastien Castagneyrol and 1 anonymous reviewer

Tritrophic interactions have a central role in ecological theory and applications [1-3]. Particularly, systems comprised of plants, herbivores and predators have historically received wide attention given their ubiquity and economic importance [4]. Although ecologists have long aimed to understand the forces that govern alternating ecological effects at successive trophic levels [5], several key open questions remain (at least partially) unanswered [6]. In particular, the analysis of complex food webs has questioned whether ecosystems can be viewed as a series of trophic chains [7,8]. Moreover, whether systems are mostly controlled by top-down (trophic cascades) or bottom-up processes remains an open question [6].

Traditionally, studies have addressed how species diversity at different food chain compartments affect the strength and direction of trophic cascades [9]. For example, many studies have tested whether biological control was more efficient with more than one species of natural enemies [10-12]. Much less attention has been given to the role of within-species variation in shaping trophic cascades [13]. In particular, whereas the impact of trait variation within species of plants or predators on successive trophic levels has been recently addressed [14,15], the impact of intraspecific herbivore variation is in its infancy (but see [16]). This is at odds with the resurgent acknowledgment of the importance of individual variation for several ecological processes operating at higher levels of biological organization [17].

Sources of variation within species can come in many flavours. In herbivores, striking ecological variation can be found among populations occurring on different host plants, which become genetically differentiated, thus forming host races [18,19]. Curiously, the impact of variation across host races on the strength of trophic cascades has, to date, not been explored. This is the gap that the manuscript by Sentis and colleagues [20] fills. They experimentally studied a curious tri-trophic system where the primary consumer, pea aphids, specializes in different plant hosts, creating intraspecific variation across biotypes. Interestingly, there is also ecological variation across lineages from the same biotype. The authors set up experimental food chains, where pea aphids from different lineages and biotypes were placed in their universal legume host (broad bean plants) and then exposed to a voracious but charming predator, ladybugs. The full factorial design of this experiment allowed the authors to measure vertical effects of intraspecific variation in herbivores on both plant productivity (top-down) and predator individual growth (bottom-up).

The results nicely uncover the mechanisms by which intraspecific differences in herbivores precipitates vertical modulation in food chains. Herbivore lineage and host-plant specialization shaped the strength of trophic cascades, but curiously these effects were not modulated by density-dependence. Further, ladybugs consuming pea aphids from different lineages and biotypes grew at distinct rates, revealing bottom-up effects of intraspecific variation in herbivores.

These findings are novel and exciting for several reasons. First, they show how intraspecific variation in intermediate food chain compartments can simultaneously reverberate both top-down and bottom-up effects. Second, they bring an evolutionary facet to the understanding of trophic cascades, providing valuable insights on how genetically differentiated populations play particular ecological roles in food webs. Finally, Sentis and colleagues’ findings [20] have critical implications well beyond their study systems. From an applied perspective, they provide an evident instance on how consumers’ evolutionary specialization matters for their role in ecosystems processes (e.g. plant biomass production, predator conversion rate), which has key consequences for biological control initiatives and invasive species management. From a conceptual standpoint, their results ignite the still neglected value of intraspecific variation (driven by evolution) in modulating the functioning of food webs, which is a promising avenue for future theoretical and empirical studies.

References

[1] Price, P. W., Bouton, C. E., Gross, P., McPheron, B. A., Thompson, J. N., & Weis, A. E. (1980). Interactions among three trophic levels: influence of plants on interactions between insect herbivores and natural enemies. Annual review of Ecology and Systematics, 11(1), 41-65. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.11.110180.000353

[2] Olff, H., Brown, V.K. & Drent, R.H. (1999). Herbivores: between plants and predators. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

[3] Tscharntke, T. & Hawkins, B.A. (2002). Multitrophic level interactions. Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511542190

[4] Agrawal, A. A. (2000). Mechanisms, ecological consequences and agricultural implications of tri-trophic interactions. Current opinion in plant biology, 3(4), 329-335. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00089-3

[5] Pace, M. L., Cole, J. J., Carpenter, S. R., & Kitchell, J. F. (1999). Trophic cascades revealed in diverse ecosystems. Trends in ecology & evolution, 14(12), 483-488. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(99)01723-1

[6] Abdala‐Roberts, L., Puentes, A., Finke, D. L., Marquis, R. J., Montserrat, M., Poelman, E. H., ... & Mooney, K. (2019). Tri‐trophic interactions: bridging species, communities and ecosystems. Ecology letters, 22(12), 2151-2167. doi: 10.1111/ele.13392

[7] Polis, G.A. & Winemiller, K.O. (1996). Food webs. Integration of patterns and dynamics. Chapmann & Hall, New York. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-7007-3

[8] Torres‐Campos, I., Magalhães, S., Moya‐Laraño, J., & Montserrat, M. (2020). The return of the trophic chain: Fundamental vs. realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web. Functional Ecology, 34(2), 521-533. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13470

[9] Polis, G. A., Sears, A. L., Huxel, G. R., Strong, D. R., & Maron, J. (2000). When is a trophic cascade a trophic cascade?. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 15(11), 473-475. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(00)01971-6

[10] Sih, A., Englund, G., & Wooster, D. (1998). Emergent impacts of multiple predators on prey. Trends in ecology & evolution, 13(9), 350-355. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01437-2

[11] Diehl, E., Sereda, E., Wolters, V., & Birkhofer, K. (2013). Effects of predator specialization, host plant and climate on biological control of aphids by natural enemies: a meta‐analysis. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50(1), 262-270. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12032

[12] Snyder, W. E. (2019). Give predators a complement: conserving natural enemy biodiversity to improve biocontrol. Biological control, 135, 73-82. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2019.04.017

[13] Des Roches, S., Post, D. M., Turley, N. E., Bailey, J. K., Hendry, A. P., Kinnison, M. T., ... & Palkovacs, E. P. (2018). The ecological importance of intraspecific variation. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2(1), 57-64. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0402-5

[14] Bustos‐Segura, C., Poelman, E. H., Reichelt, M., Gershenzon, J., & Gols, R. (2017). Intraspecific chemical diversity among neighbouring plants correlates positively with plant size and herbivore load but negatively with herbivore damage. Ecology Letters, 20(1), 87-97. doi: 10.1111/ele.12713

[15] Start, D., & Gilbert, B. (2017). Predator personality structures prey communities and trophic cascades. Ecology letters, 20(3), 366-374. doi: 10.1111/ele.12735

[16] Turcotte, M. M., Reznick, D. N., & Daniel Hare, J. (2013). Experimental test of an eco-evolutionary dynamic feedback loop between evolution and population density in the green peach aphid. The American Naturalist, 181(S1), S46-S57. doi: 10.1086/668078

[17] Bolnick, D. I., Amarasekare, P., Araújo, M. S., Bürger, R., Levine, J. M., Novak, M., ... & Vasseur, D. A. (2011). Why intraspecific trait variation matters in community ecology. Trends in ecology & evolution, 26(4), 183-192. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.01.009

[18] Drès, M., & Mallet, J. (2002). Host races in plant–feeding insects and their importance in sympatric speciation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 357(1420), 471-492. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1059

[19] Magalhães, S., Forbes, M. R., Skoracka, A., Osakabe, M., Chevillon, C., & McCoy, K. D. (2007). Host race formation in the Acari. Experimental and Applied Acarology, 42(4), 225-238. doi: 10.1007/s10493-007-9091-0

[20] Sentis, A., Bertram, R., Dardenne, N., Simon, J.-C., Magro, A., Pujol, B., Danchin, E. and J.-L. Hemptinne (2020) Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades. bioRxiv, 722140, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/722140

| Intraspecific difference among herbivore lineages and their host-plant specialization drive the strength of trophic cascades | Arnaud Sentis, Raphaël Bertram, Nathalie Dardenne, Jean-Christophe Simon, Alexandra Magro, Benoit Pujol, Etienne Danchin and Jean-Louis Hemptinne | <p>Trophic cascades, the indirect effect of predators on non-adjacent lower trophic levels, are important drivers of the structure and dynamics of ecological communities. However, the influence of intraspecific trait variation on the strength of t... |  | Community ecology, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Food webs, Population ecology | Sara Magalhães | | 2019-08-02 09:11:03 | View |

Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands

Catherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137

Resolving herbivore influences under climate variability

Recommended by Jennifer Krumins based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers

We know that herbivory can have profound influences on plant communities with respect to their distribution and productivity (recently reviewed by Jia et al. 2018). However, the degree to which these effects are realized belowground in the rhizosphere is far less understood. Indeed, many independent studies and synthesis find that the environmental context can be more important than the direct effects of herbivore activity and its removal of plant biomass (Andriuzzi and Wall 2017, Schrama et al. 2013). In spite of dedicated attention, generalizable conclusions remain a bit elusive (Sitters and Venterink 2015). Picon-Cochard and colleagues (2021) help address this research conundrum in an elegant analysis that demonstrates the interaction between long-term cattle grazing and climatic variability on primary production aboveground and belowground.

Over the course of two years, Picon-Cochard et al. (2021) measured above and belowground net primary productivity in French grasslands that had been subject to ten years of managed cattle grazing. When they compared these data with climatic trends, they find an interesting interaction among grazing intensity and climatic factors influencing plant growth. In short, and as expected, plants allocate more resources to root growth in dry years and more to above ground biomass in wet and cooler years. However, this study reveals the degree to which this is affected by cattle grazing. Grazed grasslands support warmer and dryer soils creating feedback that further and significantly promotes root growth over green biomass production.

The implications of this work to understanding the capacity of grassland soils to store carbon is profound. This study addresses one brief moment in time of the long trajectory of this grazed ecosystem. The legacy of grazing does not appear to influence soil ecosystem functioning with respect to root growth except within the environmental context, in this case, climate. This supports the notion that long-term research in animal husbandry and grazing effects on landscapes is deeded. It is my hope that this study is one of many that can be used to synthesize many different data sets and build a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of grazing and herd management within the context of a changing climate. Herbivory has a profound influence upon ecosystem health and the distribution of plant communities (Speed and Austrheim 2017), global carbon storage (Chen and Frank 2020) and nutrient cycling (Sitters et al. 2020). The analysis and results presented by Picon-Cochard (2021) help to resolve the mechanisms that underly these complex effects and ultimately make projections for the future.

References

Andriuzzi WS, Wall DH. 2017. Responses of belowground communities to large aboveground herbivores: Meta‐analysis reveals biome‐dependent patterns and critical research gaps. Global Change Biology 23:3857-3868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13675

Chen J, Frank DA. 2020. Herbivores stimulate respiration from labile and recalcitrant soil carbon pools in grasslands of Yellowstone National Park. Land Degradation & Development 31:2620-2634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3656

Jia S, Wang X, Yuan Z, Lin F, Ye J, Hao Z, Luskin MS. 2018. Global signal of top-down control of terrestrial plant communities by herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6237-6242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707984115

Picon-Cochard C, Vassal N, Martin R, Herfurth D, Note P, Louault F. 2021. Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands. bioRxiv, 2020.08.23.263137, version 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137

Schrama M, Veen GC, Bakker EL, Ruifrok JL, Bakker JP, Olff H. 2013. An integrated perspective to explain nitrogen mineralization in grazed ecosystems. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15:32-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2012.12.001

Sitters J, Venterink HO. 2015. The need for a novel integrative theory on feedbacks between herbivores, plants and soil nutrient cycling. Plant and Soil 396:421-426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2679-y

Sitters J, Wubs EJ, Bakker ES, Crowther TW, Adler PB, Bagchi S, Bakker JD, Biederman L, Borer ET, Cleland EE. 2020. Nutrient availability controls the impact of mammalian herbivores on soil carbon and nitrogen pools in grasslands. Global Change Biology 26:2060-2071. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15023

Speed JD, Austrheim G. 2017. The importance of herbivore density and management as determinants of the distribution of rare plant species. Biological Conservation 205:77-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.030

| Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands | Catherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault | <p>Background and Aims: Understanding how direct and indirect changes in climatic conditions, management, and species composition affect root production and root traits is of prime importance for the delivery of carbon sequestration services of gr... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning | Jennifer Krumins | | 2020-08-30 19:27:30 | View |

Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs

Pierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault

https://doi.org/10.1101/276592

New insights into the role of nutrient cycling in food web dynamics

Recommended by Samraat Pawar based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the factors that govern the relationship between structure, stability and functioning of food webs has been a central problem in ecology for many decades. Historically, apart from microbial and soil food webs, the role of nutrient cycling has largely been ignored in theoretical and empirical food web studies. A prime example of this is the widespread use of Lotka-Volterra type models in theoretical studies; these models per se are not designed to capture the effect of nutrients being released back into the system by interacting populations. Thus overall, we still lack a general understanding of how nutrient cycling affects food web dynamics.

A new study by Quévreux, Barot and Thébault [1] tackles this problem by building a new food web model. This model features some important biological details: trophic interactions and vital rates constrained by species' body masses (using Ecological Metabolic Theory), adaptive foraging, and stoichiometric rules to ensure meaningful conversion between carbon and nutrient flows. The authors analyze the model through detailed simulations combined with thorough sensitivity analyses of model assumptions and parametrizations (including of allometric scaling relationships). I am happy to recommend this preprint because of the novelty of the work and it's technical quality.

The study yields interesting and novel findings. Overall, nutrient cycling does have a strong effect on community dynamics. Nutrient recycling is driven mostly by consumers at low mineral nutrient inputs, and by primary producers at high inputs. The extra nutrients made available through recycling increases species' persistence at low nutrient input levels, but decreases persistence at higher input levels by increasing population oscillations (a new, nuanced perspective on the classical "paradox of enrichment"). Also, for the same level of nutrient input, food webs with nutrient recycling show more fluctuations in primary producer biomass (and less at higher trophic levels) than those without recycling, with this effect weakening in more complex food webs.

Overall, these results provide new insights, suggesting that nutrient cycling may enhance the positive effects of species richness on ecosystem stability, and point at interesting new directions for future theoretical and empirical studies.

References

[1] Quévreux, P., Barot, S. and E. Thébault (2020) Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs. bioRxiv, 276592, ver. 7 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/276592

| Interplay between the paradox of enrichment and nutrient cycling in food webs | Pierre Quévreux, Sébastien Barot and Élisa Thébault | <p>Nutrient cycling is fundamental to ecosystem functioning. Despite recent major advances in the understanding of complex food web dynamics, food web models have so far generally ignored nutrient cycling. However, nutrient cycling is expected to ... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Samraat Pawar | | 2018-11-03 21:47:37 | View |

Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa)

Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier

https://doi.org/10.1101/557066

Urban past predicts contemporary genetic structure in city rats

Recommended by Michelle DiLeo based on reviews by Torsti Schulz, ? and 1 anonymous reviewer

Urban areas are expanding worldwide, and have become a dominant part of the landscape for many species. Urbanization can fragment pre-existing populations of vulnerable species leading to population declines and the loss of connectivity. On the other hand, expansion of urban areas can also facilitate the spread of human commensals including pests. Knowledge of the features of cityscapes that facilitate gene flow and maintain diversity of pests is thus key to their management and eradication.

Cities are complex mosaics of natural and manmade surfaces, and habitat quality is not only influenced by physical aspects of the cityscape but also by socioeconomic factors and human behaviour. Constant development means that cities also change rapidly in time; contemporary urban life reflects only a snapshot of the environmental conditions faced by populations. It thus remains a challenge to identify the features that actually drive ecology and evolution of populations in cities [1]. While several studies have highlighted strong urban clines in genetic structure and adaption [2], few have considered the influence of factors beyond physical aspects of the cityscape or historical processes.

In this paper, Stragier et al. [3] sought to identify the current and past features of the cityscape and socioeconomic factors that shape genetic structure and diversity of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar, Senegal. The authors painstakingly digitized historical maps of Dakar from the time of European settlement in 1862 to present. The authors found that the main spatial genetic cline was best explained by historical cityscape features, with higher apparent gene flow and genetic diversity in areas that were connected earlier to initial European settlements. Beyond the main trend of spatial genetic structure, they found further evidence that current features of the cityscape were important. Specifically, areas with low vegetation and poor housing conditions were found to support large, genetically diverse populations. The authors demonstrate that their results are reproducible using several statistical approaches, including modeling that explicitly accounts for spatial autocorrelation.

The work of Stragier et al. [3] thus highlights that populations of city-dwelling species are the product of both past and present cityscapes. Going forward, urban evolutionary ecologists should consider that despite the potential for rapid evolution in urban landscapes, the signal of a species’ colonization can remain for generations.

References

[1] Rivkin, L. R., Santangelo, J. S., Alberti, M. et al. (2019). A roadmap for urban evolutionary ecology. Evolutionary Applications, 12(3), 384-398. doi: 10.1111/eva.12734

[2] Miles, L. S., Rivkin, L. R., Johnson, M. T., Munshi‐South, J. and Verrelli, B. C. (2019). Gene flow and genetic drift in urban environments. Molecular ecology, 28(18), 4138-4151. doi: 10.1111/mec.15221

[3] Stragier, C., Piry, S., Loiseau, A., Kane, M., Sow, A., Niang, Y., Diallo, M., Ndiaye, A., Gauthier, P., Borderon, M., Granjon, L., Brouat, C. and Berthier, K. (2020). Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa). bioRxiv, 557066, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/557066

| Interplay between historical and current features of the cityscape in shaping the genetic structure of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in Dakar (Senegal, West Africa) | Claire Stragier, Sylvain Piry, Anne Loiseau, Mamadou Kane, Aliou Sow, Youssoupha Niang, Mamoudou Diallo, Arame Ndiaye, Philippe Gauthier, Marion Borderon, Laurent Granjon, Carine Brouat, Karine Berthier | <p>Population genetic approaches may be used to investigate dispersal patterns of species living in highly urbanized environment in order to improve management strategies for biodiversity conservation or pest control. However, in such environment,... |  | Biological invasions, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology | Michelle DiLeo | | 2019-02-22 08:36:13 | View |

Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources

Thibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999

Biodiversity databases are ever more numerous, but can they be used reliably for Species Distribution Modelling?

Recommended by Nicolas Schtickzelle based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

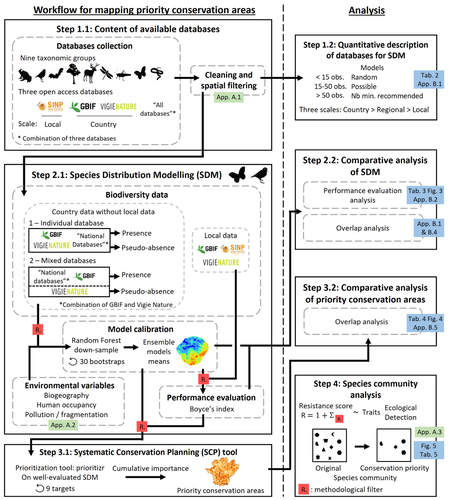

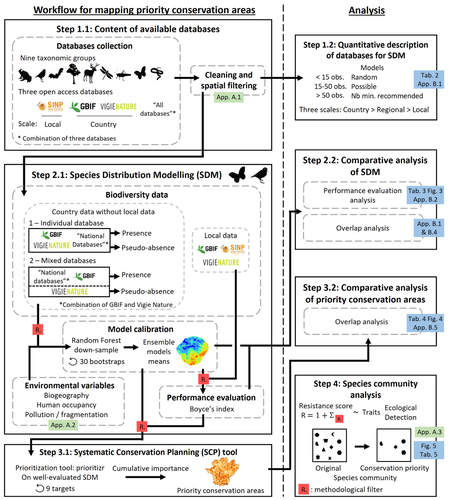

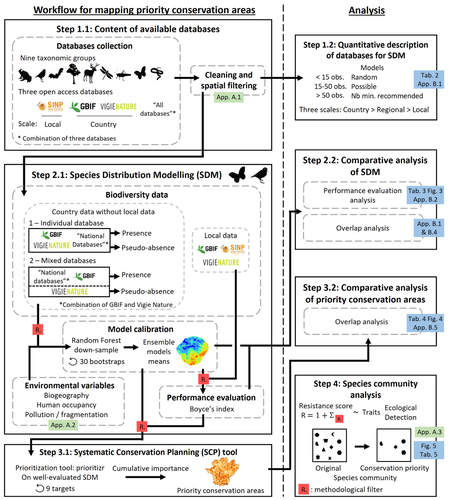

Proposing efficient guidelines for biodiversity conservation often requires the use of forecasting tools. Species Distribution Models (SDM) are more and more used to predict how the distribution of a species will react to environmental change, including any large-scale management actions that could be implemented. Their use is also boosted by the increase of publicly available biodiversity databases[1]. The now famous aphorism by George Box "All models are wrong but some are useful"[2] very well summarizes that the outcome of a model must be adjusted to, and will depend on, the data that are used to parameterize it. The question of the reliability of using biodiversity databases to parameterize biodiversity models such as SDM –but the question would also apply to other kinds of biodiversity models, e.g. Population Viability Analysis models[3]– is key to determine the confidence that can be placed in model predictions. This point is often overlooked by some categories of biodiversity conservation stakeholders, in particular the fact that some data were collected using controlled protocols while others are opportunistic.

In this study[4], the authors use a collection of databases covering a range of species as well as of geographic scales in France and using different data collection and validation approaches as a case study to evaluate the impact of data quality when performing Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA). Among their conclusions, the fact that a large-scale database (what they call the “country” level) is necessary to reliably parameterize SDM. Besides this and other conclusions of their study, which are likely to be in part specific to their case study –unfortunately for its conservation, biodiversity is complex and varies a lot–, the merit of this work lies in the approach used to test the impact of data on model predictions.

References

1. Feng, X. et al. A review of the heterogeneous landscape of biodiversity databases: Opportunities and challenges for a synthesized biodiversity knowledge base. Global Ecology and Biogeography 31, 1242–1260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13497

2. Box, G. E. P. Robustness in the Strategy of Scientific Model Building. in Robustness in Statistics (eds. Launer, R. L. & Wilkinson, G. N.) 201–236 (Academic Press, 1979). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-438150-6.50018-2.

3. Beissinger, S. R. & McCullough, D. R. Population Viability Analysis. (The University of Chicago Press, 2002).

4. Ferraille, T., Kerbiriou, C., Bigard, C., Claireau, F. & Thompson, J. D. (2023) Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.09.539999

| Integrating biodiversity assessments into local conservation planning: the importance of assessing suitable data sources | Thibaut Ferraille, Christian Kerbiriou, Charlotte Bigard, Fabien Claireau, John D. Thompson | <p>Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of land-use planning is a fundamental tool to minimize environmental impacts of artificialization. In this context, Systematic Conservation Planning (SCP) tools based on Species Distribution Models (SDM)... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Nicolas Schtickzelle | | 2023-05-11 09:41:05 | View |

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey

Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247

Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamics

Recommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data.

In the study conducted by Sidous et al. (2024), they used a large database on the abundance of spotted hyenas and their prey in Zimbabwe and Multivariate Autoregressive State-Space Models to calculate hyena and prey population densities and trends over a 60-year span. The researchers took advantage of abrupt fluctuations in elephant carcass availability that produced alternating periods of high and low carrion availability related to changing management strategies (i.e., elephant culling and water supply).

Interestingly, their analyses reveal a coupling of predator and prey densities over time, but they do not detect an effect of carcass availability on predator and prey dynamics. However, the density of prey and hyena was partially driven by the different temporal periods, suggesting some subtle effects of carrion availability on population trends. While it is acknowledged that other variables likely impact the population dynamics of hyenas and their prey, this is the first attempt to understand the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey interactions across an extensive temporal scale. I hope this helps to establish a new research line on the effect of large carrion pulses, as this is currently largely understudied, even though the occurrence of carrion pulses, such as mass mortality events, is expected to increase over time (Fey et al. 2015).

References

Courchamp, F. et al. 2000. Rabbits killing birds: modelling the hyperpredation process. J. Anim. Ecol. 69: 154-164.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2000.00383.x

Fey, S. B. et al. 2015. Recent shifts in the occurrence, cause, and magnitude of animal mass mortality events. PNAS 112: 1083-1088.

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1414894112

Mellard, J. P. et al. 2021. Effect of scavenging on predation in a food web. Ecol. Evol. 11: 6742- 6765.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7525

Moleón, M. et al. 2014. Inter-specific interactions linking predation and scavenging in terrestrial vertebrate assemblages. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 89: 1042-1054.

https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12097

Roth, J. 2003. Variability in marine resources affects arctic fox population dynamics. J. Anim. Ecol. 72: 668-676.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00739.x

Sebastián-González, E. et al. 2023. The underestimated role of carrion in diet studies. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 32: 1302-1310.

https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13707

Sidous, M. et al. 2024. Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on 1 the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology.

https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247

| Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predation

Alex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol

https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042317

Tree diversity is associated with reduced herbivory in urban forest

Recommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Ian Pearse based on reviews by Ian Pearse and Freerk Molleman

Urban ecology, the study of ecological systems in our increasingly urbanized world, is crucial to planning and redesigning cities to enhance ecosystem services (Kremer et al. 2016), human health and well-being and further conservation goals (Dallimer et al. 2012). Urban trees are a crucial component of urban streets and parks that provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration (Fung and Jim 2019), improve air quality (Lai and Kontokosta 2019), help control storm water (Johnson and Handel 2016), and conserve wildlife (Herrmann et al. 2012; de Andrade et al. 2020).

Ideally, management of urban forests strikes a balance between maintaining the health of urban trees while retaining those organisms, such as herbivores, that connect a tree to the urban ecosystem. Herbivory by arthropods can substantially affect tree growth and reproduction (Whittaker and Warrington 1985), and so understanding factors that influence herbivory in urban forests is important to effective management. At the same time, herbivorous arthropods are important as key components of urban bird diets (Airola and Greco 2019) and provide a backyard glimpse at forest ecosystems in an increasingly built environment (Pearse 2019). Maintenance of arthropod predators may be one way to retain arthropods in urban forests while keeping detrimental outbreaks of herbivores in check. In “Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbors and predation” Stemmelen and colleagues (Stemmelen et al. 2020) use a clever sampling design to show that insect herbivory decreases as the diversity of neighboring trees increased. By placing artificial larvae out on trees, they provide evidence that increased predation in higher diversity urban forest patches might drive patterns in herbivory. The paper also demonstrates the importance of tree species identity in determining leaf herbivory.

The implications of this research for urban foresters is that deliberately planting diverse urban forests will help manage insect herbivores and should thus improve tree health. Potential knock-on effects could be seen for the ecosystem services provided by urban forests. While it might be tempting to simply plant more of the species that are subject to low current rates of herbivory, other research on the long-term vulnerability of monocultures to attack by specialist pathogens and herbivores (Tooker and Frank 2012) cautions against such an approach. Furthermore, the importance of urban forest insects to birds, including migrating birds, argues for managing urban forests more holistically (Greco and Airola 2018).

Stemmelen et al. (2020) used an observational approach focused on urban forests in Montreal, Canada in their research. Their findings suggest follow-up research focused on a broader cross-section of urban forests across latitudes, as well as experimental research. Experiments could, for example, exclude avian predators with netting (e.g. (Marquis and Whelan 1994)) to evaluate the relative importance of birds to managing urban insects on trees, as well as the flip side of that equation, the important to birds of insects on urban trees.

In summary, Stemmelen and colleague’s manuscript illustrates clever sampling and use of observational data to infer broader ecological patterns. It is worth reading to better understand the role of diversity in driving plant-insect community interactions and given the implications of the findings for sustainable long-term management of urban forests.

References

Airola, D. and Greco, S. (2019). Birds and oaks in California’s urban forest. Int. Oaks, 30, 109–116.

de Andrade, A.C., Medeiros, S. and Chiarello, A.G. (2020). City sloths and marmosets in Atlantic forest fragments with contrasting levels of anthropogenic disturbance. Mammal Res., 65, 481–491. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13364-020-00492-0

Dallimer, M., Irvine, K.N., Skinner, A.M.J., Davies, Z.G., Rouquette, J.R., Maltby, L.L., et al. (2012). Biodiversity and the Feel-Good Factor: Understanding Associations between Self-Reported Human Well-being and Species Richness. Bioscience, 62, 47–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.9

Fung, C.K.W. and Jim, C.Y. (2019). Microclimatic resilience of subtropical woodlands and urban-forest benefits. Urban For. Urban Green., 42, 100–112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.05.014

Greco, S.E. and Airola, D.A. (2018). The importance of native valley oaks (Quercus lobata) as stopover habitat for migratory songbirds in urban Sacramento, California, USA. Urban For. Urban Green., 29, 303–311. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.01.005

Herrmann, D.L., Pearse, I.S. and Baty, J.H. (2012). Drivers of specialist herbivore diversity across 10 cities. Landsc. Urban Plan., 108, 123–130. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.08.007

Johnson, L.R. and Handel, S.N. (2016). Restoration treatments in urban park forests drive long-term changes in vegetation trajectories. Ecol. Appl., 26, 940–956. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/14-2063

Kremer, P., Hamstead, Z., Haase, D., McPhearson, T., Frantzeskaki, N., Andersson, E., et al. (2016). Key insights for the future of urban ecosystem services research. Ecol. Soc., 21: 29. doi: http://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08445-210229

Lai, Y. and Kontokosta, C.E. (2019). The impact of urban street tree species on air quality and respiratory illness: A spatial analysis of large-scale, high-resolution urban data. Heal. Place, 56, 80–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.01.016

Marquis, R.J. and Whelan, C.J. (1994). Insectivorous birds increase growth of white oak through consumption of leaf-chewing insects. Ecology, 75, 2007–2014. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1941605

Pearse, I.S. (2019). Insect herbivores on urban native oak trees. Int. Oaks, 30, 101–108.

Stemmelen, A., Paquette, A., Benot, M.-L., Kadiri, Y., Jactel, H. and Castagneyrol, B. (2020) Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predation. bioRxiv, 2020.04.15.042317, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042317

Tooker, J. F., and Frank, S. D. (2012). Genotypically diverse cultivar mixtures for insect pest management and increased crop yields. J. Appl. Ecol., 49(5), 974-985. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02173.x

Whittaker, J.B. and Warrington, S. (1985). An experimental field study of different levels of insect herbivory induced By Formica rufa predation on Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) III. Effects on Tree Growth. J. Appl. Ecol., 22, 797. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2403230

| Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predation | Alex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol | <p>Insect herbivory is an important component of forest ecosystems functioning and can affect tree growth and survival. Tree diversity is known to influence insect herbivory in natural forest, with most studies reporting a decrease in herbivory wi... |  | Biodiversity, Biological control, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | | 2020-04-20 13:49:36 | View |

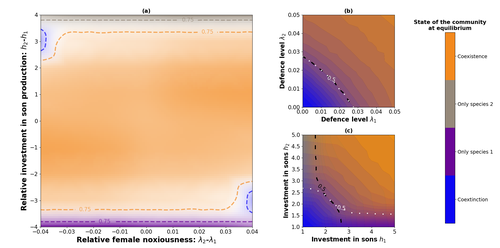

Mullerian and Batesian mimicry can influence population and community dynamics

Recommended by Amanda Franklin based on reviews by Jesus Bellver and 1 anonymous reviewer

Mimicry between species has long attracted the attention of scientists. Over a century ago, Bates first proposed that palatable species should gain a benefit by resembling unpalatable species (Bates 1862). Not long after, Müller suggested that there could also be a mutual advantage for two unpalatable species to mimic one another to reduce predator error (Müller 1879). These forms of mimicry, Batesian and Müllerian, are now widely studied, providing broad insights into behaviour, ecology and evolution.

Numerous taxa, including both invertebrates and vertebrates, show examples of Batesian or Müllerian mimicry. Bees and wasps provide a particularly interesting case due to the differences in defence between females and males of the same species. While both males and females may display warning colours, only females can sting and inject venom to cause pain and allow escape from predators. Therefore, males are palatable mimics and can resemble females of their own species or females of another species (dual sex-limited mimicry). This asymmetry in defence could have impacts on both population structure and community assembly, yet research into mimicry largely focuses on systems without sex differences.

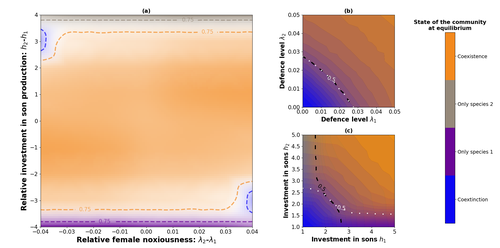

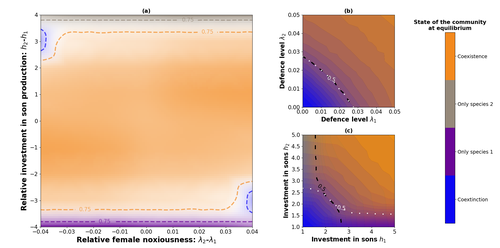

Here, Boutin and colleagues (2023) use a differential equations model to explore the effect of mimicry on population structure and community assembly for sex-limited defended species. Specifically, they address three questions, 1) how do female noxiousness and sex-ratio influence the extinction risk of a single species?; 2) what is the effect of mimicry on species co-existence? and 3) how does dual sex-limited mimicry influence species co-existence? Their results reveal contexts in which populations with undefended males can persist, the benefit of Müllerian mimicry for species coexistence and that dual sex-limited mimicry can have a destabilising impact on species coexistence.

The results not only contribute to our understanding of how mimicry is maintained in natural systems but also demonstrate how changes in relative abundance or population structure of one species could impact another species. Further insight into the population and community dynamics of insects is particularly important given the current population declines (Goulson 2019; Seibold et al 2019).

References

Bates, H. W. 1862. Contributions to the insect fauna of the Amazon Valley, Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23:495- 566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x

Boutin, M., Costa, M., Fontaine, C., Perrard, A., Llaurens, V. 2022 Influence of sex-limited mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153

Goulson, D. 2019. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Curr. Biol. 29: R967-R971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.069

Müller, F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia; a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Roy. Entom. Roc. 1879:20-29.

Seibold, S., Gossner, M. M., Simons, N. K., Blüthgen, N., Müller, J., Ambarlı, D., ... & Weisser, W. W. 2019. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature, 574: 671-674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1684-3

| Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach | Maxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens | <p style="text-align: justify;">Positive ecological interactions, such as mutualism, can play a role in community structure and species co-existence. A well-documented case of mutualistic interaction is Mullerian mimicry, the convergence of colour... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism | Amanda Franklin | | 2022-10-25 19:11:55 | View |

Assessing bat-vehicle collision risks using acoustic 3D tracking

Recommended by Gloriana Chaverri based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ? based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ?

The loss of biodiversity is an issue of great concern, especially if the extinction of species or the loss of a large number of individuals within populations results in a loss of critical ecosystem services. We know that the most important threat to most species is habitat loss and degradation (Keil et al., 2015; Pimm et al., 2014); the latter can be caused by multiple anthropogenic activities, including pollution, introduction of invasive species and fragmentation (Brook et al., 2008; Scanes, 2018). Roads are a major cause of habitat fragmentation, isolating previously connected populations and being a direct source of mortality for animals that attempt to cross them (Spellberg, 1998).

While most studies have focused on the effect of roads on larger mammals (Bartonička et al., 2018; Litvaitis and Tash, 2008), in recent years many researchers have grown increasingly concerned about the risk of collision between bats and vehicles (Fensome and Mathews, 2016). For example, a recent publication by Medinas et al. (2021) found 509 bat casualties along a 51-km-long transect during a period of 3 years. Their study provides extremely valuable information to asses which factors primarily drive bat mortality on roads, yet it required a substantial investment of time coupled with the difficulty of detecting bat carcasses. Other studies have used acoustic monitoring as a proxy to gauge risk of collision based on estimates of bat density along roads (reviewed in Fensome and Mathews 2016); while the results of such studies are valuable, the number of passes recorded does not necessarily equal collision risk, as many species may simply avoid crossing the roads. Understanding the risk of collisions is of vital importance for adequate planning of road construction, particularly for key sites that harbor threatened bat species or unusually large populations, especially if these are already greatly impacted by other anthropogenic activities (e.g. wind turbines; Kunz et al. 2007) or unusually deadly pathogens (e.g. white-nose syndrome; Blehert et al. 2009).

The study by Roemer et al. (2020) titled “Influence of local landscape and time of year on bat-road collision risks”, is a welcome addition to our understanding of bat collision risk as it employs a more accurate assessment of bat collision risk based on acoustic monitoring and tracking of flight paths. The goal of the study of Roemer and collaborators, which was conducted at 66 study sites in the Mediterranean region, is to provide an assessment of collision risk based on bat activity near roads. They collected a substantial amount of information for several species: more than 30,000 estimated flight trajectories for 21+ species, including Barbastella barbastellus, Myotis spp., Plecotus sp., Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, Miniopterus schreibersii, Pipistrellus spp., Nyctalus leisleri, and others. They assess risk based on estimates of 1) species abundance from acoustic monitoring, 2) direction of flight paths along roads, and 3) bat-vehicle co-occurrence.

Their findings suggest that risk is habitat, species, guild, and season-specific. Roads within forested habitats posed the largest threats for most species, particularly since most flights within these habitats occurred at the zone of collision risk. They also found that bats typically fly parallel to the road axis regardless of habitat type, which they argue supports the idea that bats may use roads as corridors. The results of their study, as expected, also show that the majority of bat passes were detected during summer or autumn, depending on species, yet they provide novel findings of an increase in risky behaviors during autumn, when the number of passes at the zone of collision risk increased significantly. Their results also suggest that mid-range echolocators, a classification that is based on call design and parameters (Frey-Ehrenbold et al., 2013), had a larger portion of flights in the zone at risk, thus potentially making them more susceptible than short and long-range echolocators to collisions with vehicles.

The methods employed by Roemer et al. (2020) could further help us determine how roads pose species and site-specific threats in a diversity of places without the need to invest a significant amount of time locating bat carcasses. Their findings are also important as they could provide valuable information for deciding where new roads should be constructed, particularly if the most vulnerable species are abundant, perhaps due to the presence of important roost sites. They also show how habitats near larger roads could increase threats, providing an important first step for recommendations regarding road construction and maintenance. As pointed out by one reviewer, one possible limitation of the study is that the results are not supported by the identification of carcasses. For example, does an increase in the number of identified flights at the zone of risk really translate into an increase in the number of collisions? Regardless of the latter, the paper’s methods and results are very valuable and provide an important step towards developing additional tools to assess bat-vehicle collision risks.

References

[1] Bartonička T, Andrášik R, Duľa M, Sedoník J, Bíl M (2018) Identification of local factors causing clustering of animal-vehicle collisions. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 82, 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21467

[2] Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, Coleman JTH, Darling SR, Gargas A, Niver R, Okoniewski JC, Rudd RJ, Stone WB (2009) Bat White-Nose Syndrome: An Emerging Fungal Pathogen? Science, 323, 227–227. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1163874

[3] Brook BW, Sodhi NS, Bradshaw CJA (2008) Synergies among extinction drivers under global change. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.03.011

[4] Fensome AG, Mathews F (2016) Roads and bats: a meta-analysis and review of the evidence on vehicle collisions and barrier effects. Mammal Review, 46, 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/mam.12072

[5] Frey‐Ehrenbold A, Bontadina F, Arlettaz R, Obrist MK (2013) Landscape connectivity, habitat structure and activity of bat guilds in farmland-dominated matrices. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50, 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12034

[6] Keil P, Storch D, Jetz W (2015) On the decline of biodiversity due to area loss. Nature Communications, 6, 8837. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9837

[7] Kunz TH, Arnett EB, Erickson WP, Hoar AR, Johnson GD, Larkin RP, Strickland MD, Thresher RW, Tuttle MD (2007) Ecological impacts of wind energy development on bats: questions, research needs, and hypotheses. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 5, 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[315:EIOWED]2.0.CO;2

[8] Litvaitis JA, Tash JP (2008) An Approach Toward Understanding Wildlife-Vehicle Collisions. Environmental Management, 42, 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9108-4

[9] Medinas D, Marques JT, Costa P, Santos S, Rebelo H, Barbosa AM, Mira A (2021) Spatiotemporal persistence of bat roadkill hotspots in response to dynamics of habitat suitability and activity patterns. Journal of Environmental Management, 277, 111412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111412

[10] Pimm SL, Jenkins CN, Abell R, Brooks TM, Gittleman JL, Joppa LN, Raven PH, Roberts CM, Sexton JO (2014) The biodiversity of species and their rates of extinction, distribution, and protection. Science, 344. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1246752

[11] Roemer C, Coulon A, Disca T, Bas Y (2020) Influence of local landscape and time of year on bat-road collision risks. bioRxiv, 2020.07.15.204115, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.204115

[12] Scanes CG (2018) Chapter 19 - Human Activity and Habitat Loss: Destruction, Fragmentation, and Degradation. In: Animals and Human Society (eds Scanes CG, Toukhsati SR), pp. 451–482. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805247-1.00026-5

[13] Spellerberg I (1998) Ecological effects of roads and traffic: a literature review. Global Ecology & Biogeography Letters, 7, 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-822x.1998.00308.x

| Influence of local landscape and time of year on bat-road collision risks | Charlotte Roemer, Aurélie Coulon, Thierry Disca, and Yves Bas | <p>Roads impact bat populations through habitat loss and collisions. High quality habitats particularly increase bat mortalities on roads, yet many questions remain concerning how local landscape features may influence bat behaviour and lead to hi... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Human impact, Landscape ecology | Gloriana Chaverri | | 2020-07-20 10:56:29 | View |

Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences

Anna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan

https://doi.org/10.1101/387456

Upscaling the neighborhood: how to get species diversity, abundance and range distributions from local presence/absence data

Recommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer

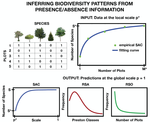

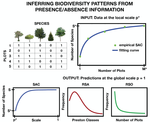

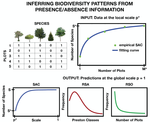

How do you estimate the biodiversity of a whole community, or the distribution of abundances and ranges of its species, from presence/absence data in scattered samples?

It all starts with the collector's dilemma: if you double the number of samples, you will not get double the number of species, since you will find many of the same common species, and only a few new rare ones.

This non-additivity has prompted many ecologists to study the Species-Area Relationship. A common theoretical approach has been to connect this spatial pattern to the overall distribution of how common or rare a species can be. At least since Fisher's celebrated log-series [1], ecologists have been trying to, first, infer the shape of the Species Abundance Distribution, and then, use it to predict how many species should be found in a given area or a given number of samples. This has found many applications, from microbial communities to tropical forests, from estimating the number of yet-unknown species to predicting how much biodiversity may be lost if a fraction of the habitat is removed.

In this elegant work, Tovo et al. [2] propose a method that starts only from presence/absence data over a number of samples, and provides the community's diversity, as well as its abundance and range size distributions. This method is simple, analytically explicit, and accurate: the authors test it on the classic Pasoh and Barro Colorado Island tropical forest datasets, and on simulated data. They make a very laudable effort in both explaining its theoretical underpinnings, and proposing a straightforward step-by-step guide to applying it to data.

The core of Tovo et al's method is a simple property: the scale invariance of the Negative Binomial (NB) distribution. Subsampling from a NB gives another NB, where a single parameter has changed. Therefore, if the Species Abundance Distribution is close enough to some NB (which is flexible enough to accommodate all the data here), we can estimate how this parameter changes when going from (1) a single sample to (2) all the available samples, and from there, extrapolate to (3) the entire community.

This principle was first applied by the authors in a previous study [3] that required abundance data in the samples, rather than just presence/absence. Given that binary occurrence data is far more available in a variety of empirical settings, this extension is worthwhile (including its new predictions on range size distributions), and it deserves to be widely known and tested.

ADDITIONAL COMMENTS

1) To explain the novelty of the authors' contribution, it is useful to look at competing techniques.

Some ""parametric"" approaches try to infer the whole-community Species Abundance Distribution (SAD) by guessing its functional form (Gaussian, power-law, log-series...) and fitting its parameters from sampled data. The issue is that this distribution shape may not remain in the same family as we increase the sampling effort or area, so the regression problem may not be well-defined. This is where the Negative Binomial's scale invariance is useful.

Other ""non-parametric"" approaches have renounced guessing the whole SAD: they simply try to approximate of its tail of rare species, by looking at how many species are found in only one (or a few) samples. From this, they derive an estimate of biodiversity that is agnostic to the rest of the SAD. Tovo et al. [2] show the issue with these approaches: they extrapolate from the properties of individual samples to the whole community, but do not properly account for the bias introduced by the amount of sampling (the intermediate scale (2) in the summary above).

2) The main condition for all such approaches to work is well-mixedness: each sample should be sufficiently like a lot drawn from the same skewed lottery. As long as that condition applies, finding the best approach is a theoretical matter of probabilities and combinatorics that may, in time, be given a definite answer.

The authors also show that ""well-mixed"" is not as restrictive as it sounds: the method works both on real data (which is never perfectly mixed) and on simulations where species are even more spatially clustered than the empirical data. In addition, the Negative Binomial's scale invariance entails that, if it works well enough at some spatial scale, it will also work at all higher scales (until one reaches the edges of the sufficiently-well-mixed community)

3) One may ask: why the Negative Binomial as a Species Abundance Distribution?

If one wishes for some dynamical explanation, the Negative Binomial can be derived from neutral birth and death process with immigration, as shown by the authors in [3]. But to be applied to data, it should only be able to approximate the empirical distribution well enough (at all relevant scales). Depending on one's taste, this type of probabilistic approaches can be interpreted as:

- purely phenomenological, describing only the observational process of sampling from an existing state of affairs, not the ecological processes that gave rise to that state.

- a null model, from which everything in practice is expected to deviate to some extent.

- or a way to capture the statistical forces that tend to induce stable relationships between different patterns (as long as no ecological process opposes them strongly enough).

References

[1] Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S., & Williams, C. B. (1943). The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 42-58. doi: 10.2307/1411

[2] Tovo, A., Formentin, M., Suweis, S., Stivanello, S., Azaele, S., & Maritan, A. (2019). Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences. bioRxiv, 387456, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. doi: 10.1101/387456

[3] Tovo, A., Suweis, S., Formentin, M., Favretti, M., Volkov, I., Banavar, J. R., Azaele, S., & Maritan, A. (2017). Upscaling species richness and abundances in tropical forests. Science Advances, 3(10), e1701438. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701438

| Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences | Anna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan | <p>Biodiversity provides support for life, vital provisions, regulating services and has positive cultural impacts. It is therefore important to have accurate methods to measure biodiversity, in order to safeguard it when we discover it to be thre... |  | Macroecology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | | 2018-08-09 16:44:09 | View |

based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Jean-François Arnoldi, Wojciech Uszko and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ?

based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ?

based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer

based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer