Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

12 Mar 2023

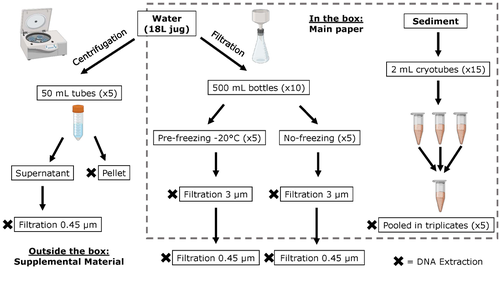

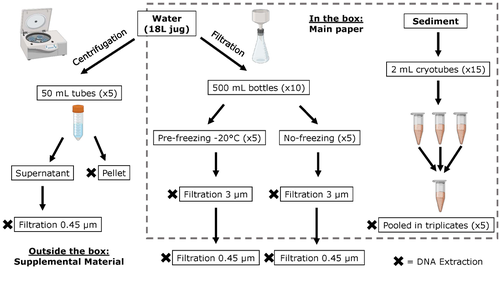

Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities.Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388Processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters from coastal lagoonsRecommended by Claudia Piccini based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Rutger De WitCoastal lagoons are among the most productive natural ecosystems on Earth. These relatively closed basins are important habitats and nursery for endemic and endangered species and are extremely vulnerable to nutrient input from the surrounding catchment; therefore, they are highly susceptible to anthropogenic influence, pollution and invasion (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). In general, coastal lagoons exhibit great spatial and temporal variability in their physicochemical water characteristics due to the sporadic mixing of freshwater with marine influx. One of the alternatives for monitoring communities or target species in aquatic ecosystems is the environmental DNA (eDNA), since overcomes some limitations from traditional methods and enables the investigation of multiple species from a single sample (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). In coastal lagoons, where the water turbidity is highly variable, there is a major challenge for monitoring the eDNA because filtering turbid water to obtain the eDNA is problematic (filters get rapidly clogged, there is organic and inorganic matter accumulation, etc.). The study by Turba et al. (2023) analyzes different ways of dealing with eDNA sampling and processing in turbid waters and sediments of coastal lagoons, and offers guidelines to obtain unbiased results from the subsequent sequencing using 12S (fish) and 16S (Bacteria and Archaea) universal primers. They analyzed the effect on taxa detection of: i) freezing or not prior to filtering; ii) freezing prior to centrifugation to obtain a sample pellet; and iii) using frozen sediment samples as a proxy of what happens in the water. The authors propose these different alternatives (freeze, do not freeze, sediment sampling) because they consider that they are the easiest to carry out. They found that freezing before filtering using a 3 µm pore size filter had no effects on community composition for either primer, and therefore it is a worthwhile approach for comparison of fish, bacteria and archaea in this kind of system. However, significantly different bacterial community composition was found for sediment compared to water samples. Also, in sediment samples the replicates showed to be more heterogeneous, so the authors suggest increasing the number of replicates when using sediment samples. Something that could be a concern with the study is that the rarefaction curves based on sequencing effort for each protocol did not saturate in any case, this being especially evident in sediment samples. The authors were aware of this, used the slopes obtained from each curve as a measure of comparison between samples and considering that the sequencing depth did not meet their expectations, they managed to achieve their goal and to determine which protocol is the most promising for eDNA monitoring in coastal lagoons. Although there are details that could be adjusted in relation to this item, I consider that the approach is promising for this type of turbid system. References Pérez-Ruzafa A, Campillo S, Fernández-Palacios JM, García-Lacunza A, García-Oliva M, Ibañez H, Navarro-Martínez PC, Pérez-Marcos M, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Quispe-Becerra JI, Sala-Mirete A, Sánchez O, Marcos C (2019) Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00026 Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 Turba R, Thai GH, Jacobs DK (2023) Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.495388, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388 | Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. | Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are an important habitat for endemic and threatened species in California that have suffered impacts from urbanization and increased drought. Environmental DNA has been promoted as a way to aid in th... |  | Biodiversity, Community genetics, Conservation biology, Freshwater ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Claudia Piccini | David Murray-Stoker | 2022-06-20 20:31:51 | View |

20 Feb 2019

Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in SenegalNathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat https://doi.org/10.1101/442160Are all the roads leading to Rome?Recommended by Simon Blanchet based on reviews by Nadia Aubin-Horth and 1 anonymous reviewerIdentifying the factors which favour the establishment and spread of non-native species in novel environments is one of the keys to predict - and hence prevent or control - biological invasions. This includes biological factors (i.e. factors associated with the invasive species themselves), and one of the prevailing hypotheses is that some species traits may explain their impressive success to establish and spread in novel environments [1]. In animals, most research studies have focused on traits associated with fecundity, age at maturity, level of affiliation to humans or dispersal ability for instance. The “composite picture” of the perfect (i.e. successful) invader that has gradually emerged is a small-bodied animal strongly affiliated to human activities with high fecundity, high dispersal ability and a super high level of plasticity. Of course, the story is not that simple, and actually a perfect invader sometimes – if not often- takes another form… Carrying on to identify what makes a species a successful invader or not is hence still an important research axis with major implications. References [1] Jeschke, J. M., & Strayer, D. L. (2006). Determinants of vertebrate invasion success in Europe and North America. Global Change Biology, 12(9), 1608-1619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01213.x | Differential immune gene expression associated with contemporary range expansion of two invasive rodents in Senegal | Nathalie Charbonnel, Maxime Galan, Caroline Tatard, Anne Loiseau, Christophe Diagne, Ambroise Dalecky, Hugues Parrinello, Stephanie Rialle, Dany Severac and Carine Brouat | <p>Background: Biological invasions are major anthropogenic changes associated with threats to biodiversity and health. What determines the successful establishment of introduced populations still remains unsolved. Here we explore the appealing as... |  | Biological invasions, Eco-immunology & Immunity, Population ecology | Simon Blanchet | 2018-10-14 12:21:52 | View | |

28 Mar 2019

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snailKatja Leicht, Otto Seppälä https://doi.org/10.1101/449777Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snailsRecommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentisAmongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor. References [1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704 | Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail | Katja Leicht, Otto Seppälä | <p>Global climate change imposes a serious threat to natural populations of many species. Estimates of the effects of climate change‐mediated environmental stresses are, however, often based only on their direct effects on organisms, and neglect t... |  | Climate change | vincent calcagno | 2018-10-22 22:19:22 | View | |

30 May 2024

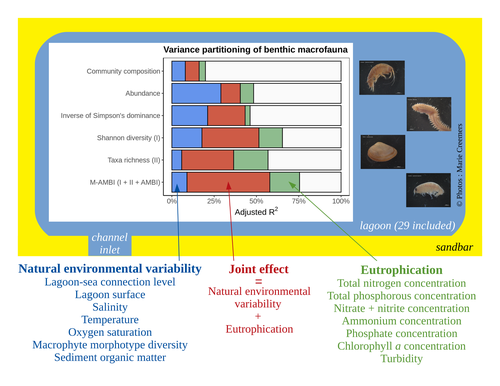

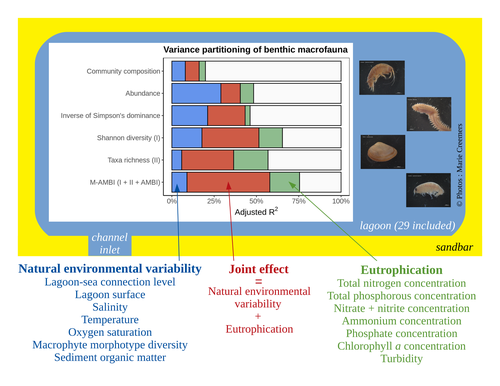

Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoonsAuriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.18.504439Untangling Eutrophication Effects on Coastal Lagoon EcosystemsRecommended by Nathalie Niquil based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright based on reviews by Kaylee P. Smit, Matthew J. Pruden and Kendyl Wright

Disentangling the effects on ecosystem structure and functioning of natural and human-induced impacts in transitional waters is a great challenge in coast ecology. This is due to the observation that the ecosystems of transitional waters are naturally dynamic systems with characteristics of stressed systems. For example, the benthic communities present low species richness and high abundance of species with a high tolerance to variations, e.g., salinity. This general observation is known as the paradigm of the “Transitional Waters Quality Paradox” (Zaldívar et al., 2008) derived from the previously described “Estuarine Quality Paradox” (Elliott and Quintino, 2007). In Jones et al. (2024) “Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons”, a great diversity of lagoons is analyzed to disentangle the effects of eutrophication from those of natural environmental variability on benthic macroinvertebrates and understanding the links between environmental variables affecting benthic macroinvertebrates. These authors use a very elegant set of numerical approaches, including correlograms, linear models and variance partitioning. They apply this suite to a dataset of macrobenthic invertebrate abundances and environmental variables from 29 Mediterranean coastal lagoons in France. Through this suite of analyses, they demonstrate the strong complexity of the mechanisms interplaying in a situation of eutrophication on lagoon macrobenthos. The mechanisms involved are direct, like toxicity, or indirect, for example, through modifications of the sediment's biogeochemistry. Such a result on the different interactions involved is very important in the context of the search for indicators to define ecosystem status. Improving the definition of metrics is essential in environmental management decisions. References Elliott, M. and Quintino, V. (2007) The estuarine quality paradox, environmental homeostasis and the difficulty of detecting anthropogenic stress in naturally stressed areas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 54, 640–645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.02.003 Zaldívar, J. (2008). Eutrophication in transitional waters: an overview. https://doi.org/10.1285/I18252273V2N1P1 | Disentangling the effects of eutrophication and natural variability on macrobenthic communities across French coastal lagoons | Auriane G. Jones, Gauthier Schaal, Aurélien Boyé, Marie Creemers, Valérie Derolez, Nicolas Desroy, Annie Fiandrino, Théophile L. Mouton, Monique Simier, Niamh Smith, Vincent Ouisse | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are transitional ecosystems that host a unique diversity of species and support many ecosystem services. Owing to their position at the interface between land and sea, they are also subject to increa... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Marine ecology | Nathalie Niquil | Matthew J. Pruden | 2023-09-08 11:26:01 | View |

01 Mar 2022

Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiringTimothée Poisot https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2How to evaluate and interpret the contribution of species turnover and interaction rewiring when comparing ecological networks?Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus and 1 anonymous reviewer

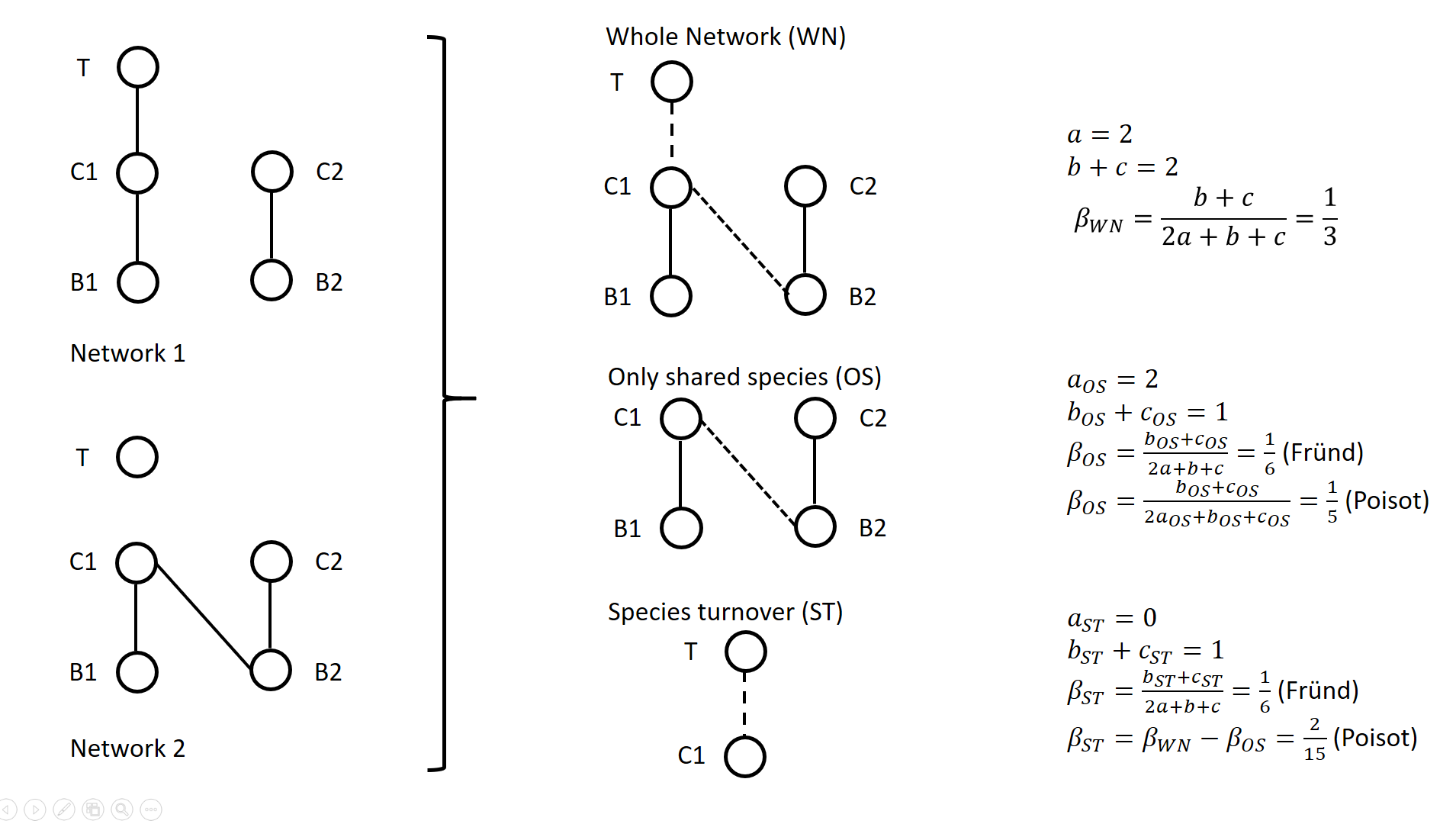

A network includes a set of vertices or nodes (e.g., species in an interaction network), and a set of edges or links (e.g., interactions between species). Whether and how networks vary in space and/or time are questions often addressed in ecological research. Two ecological networks can differ in several extents: in that species are different in the two networks and establish new interactions (species turnover), or in that species that are present in both networks establish different interactions in the two networks (rewiring). The ecological meaning of changes in network structure is quite different according to whether species turnover or interaction rewiring plays a greater role. Therefore, much attention has been devoted in recent years on quantifying and interpreting the relative changes in network structure due to species turnover and/or rewiring. Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to partition the global variation in structure between networks, \( \beta_{WN} \) (WN = Whole Network) into two terms: \( \beta_{OS} \) (OS = Only Shared species) and \( \beta_{ST} \) (ST = Species Turnover), such as \( \beta_{WN} = \beta_{OS} + \beta_{ST} \). The calculation lays on enumerating the interactions between species that are common or not to two networks, as illustrated on Figure 1 for a simple case. Specifically, Poisot et al. (2012) proposed to use a Sorensen type measure of network dissimilarity, i.e., \( \beta_{WN} = \frac{a+b+c}{(2a+b+c)/2} -1=\frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} \) , where \( a \) is the number of interactions shared between the networks, while \( b \) and \( c \) are interaction numbers unique to one and the other network, respectively. \( \beta_{OS} \) is calculated based on the same formula, but only for the subnetworks including the species common to the two networks, in the form \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a_{OS}+b_{OS}+c_{OS}} \) (e.g., Fig. 1). \( \beta_{ST} \) is deduced by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and represents in essence a "dissimilarity in interaction structure introduced by dissimilarity in species composition" (Poisot et al. 2012).

Figure 1. Ecological networks exemplified in Fründ (2021) and discussed in Poisot (2022). a is the number of shared links (continuous lines in right figures), while b+c is the number of edges unique to one or the other network (dashed lines in right figures). Alternatively, Fründ (2021) proposed to define \( \beta_{OS} = \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}}{2a+b+c} \) and \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} \), where \( b_{ST}=b-b_{OS} \) and \( c_{ST}=c-c_{OS} \) , so that the components \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) have the same denominator. In this way, Fründ (2021) partitioned the count of unique \( b+c=b_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST} \) interactions, so that \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) sums to \( \frac{b_{OS}+c_{OS}+b_{ST}+c_{ST}}{2a+b+c} = \frac{b+c}{2a+b+c} = \beta_{WN} \). Fründ (2021) advocated that this partition allows a more sensible comparison of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \), in terms of the number of links that contribute to each component. For instance, let us consider the networks 1 and 2 in Figure 1 (left panel) such as \( a_{OS}=2 \) (continuous lines in right panel), \( b_{ST} + c_{ST} = 1 \) and \( b_{OS} + c_{OS} = 1 \) (dashed lines in right panel), and thereby \( a = 2 \), \( b+c=2 \), \( \beta_{WN} = 1/3 \). Fründ (2021) measured \( \beta_{OS}=\beta_{ST}=1/6 \) and argued that it is appropriate insofar as it reflects that the number of unique links in the OS and ST components contributing to network dissimilarity (dashed lines) are actually equal. Conversely, the formula of Poisot et al. (2012) yields \( \beta_{OS}=1/5 \), hence \( \beta_{ST} = \frac{1}{3}-\frac{1}{5}=\frac{2}{15}<\beta_{OS} \). Fründ (2021) thus argued that the method of Poisot tends to underestimate the contribution of species turnover. To clarify and avoid misinterpretation of the calculation of \( \beta_{OS} \) and \( \beta_{ST} \) in Poisot et al. (2012), Poisot (2022) provides a new, in-depth mathematical analysis of the decomposition of \( \beta_{WN} \). Poisot et al. (2012) quantify in \( \beta_{OS} \) the actual contribution of rewiring in network structure for the subweb of common species. Poisot (2022) thus argues that \( \beta_{OS} \) relates only to the probability of rewiring in the subweb, while the definition of \( \beta_{OS} \) by Fründ (2021) is relative to the count of interactions in the global network (considered in denominator), and is thereby dependent on both rewiring probability and species turnover. Poisot (2022) further clarifies the interpretation of \( \beta_{ST} \). \( \beta_{ST} \) is obtained by subtracting \( \beta_{OS} \) from \( \beta_{WN} \) and thus represents the influence of species turnover in terms of the relative architectures of the global networks and of the subwebs of shared species. Coming back to the example of Fig.1., the Poisot et al. (2012) formula posits that \( \frac{\beta_{ST}}{\beta_{WN}}=\frac{2/15}{1/3}=2/5 \), meaning that species turnover contributes two-fifths of change in network structure, while rewiring in the subweb of common species contributed three fifths. Conversely, the approach of Fründ (2021) does not compare the architectures of global networks and of the subwebs of shared species, but considers the relative contribution of unique links to network dissimilarity in terms of species turnover and rewiring. Poisot (2022) concludes that the partition proposed in Fründ (2021) does not allow unambiguous ecological interpretation of rewiring. He provides guidelines for proper interpretation of the decomposition proposed in Poisot et al. (2012). References Fründ J (2021) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: how to partition rewiring and species turnover components. Ecosphere, 12, e03653. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3653 Poisot T, Canard E, Mouillot D, Mouquet N, Gravel D (2012) The dissimilarity of species interaction networks. Ecology Letters, 15, 1353–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12002 Poisot T (2022) Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring. EcoEvoRxiv Preprints, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/gxhu2 | Dissimilarity of species interaction networks: quantifying the effect of turnover and rewiring | Timothée Poisot | <p style="text-align: justify;">Despite having established its usefulness in the last ten years, the decomposition of ecological networks in components allowing to measure their β-diversity retains some methodological ambiguities. Notably, how to ... |  | Biodiversity, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2021-07-31 00:18:41 | View | |

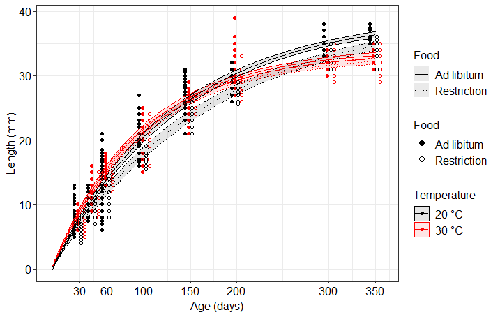

17 May 2023

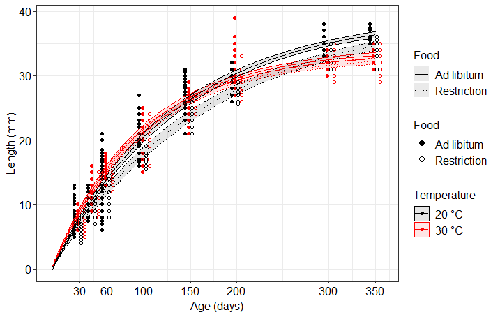

Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectothermsSimon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3Effect of food conditions on the Temperature-Size RuleRecommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Wolf Blanckenhorn and Wilco VerberkTemperature-size rule (TSR) is a phenomenon of plastic changes in body size in response to temperature, originally observed in more than 80% of ectothermic organisms representing various groups (Atkinson 1994). In particular, ectotherms were observed to grow faster and reach smaller size at higher temperature and grow slower and achieve larger size at lower temperature. This response has fired the imagination of researchers since its invention, due to its counterintuitive pattern from an evolutionary perspective (Berrigan and Charnov 1994). The main question to be resolved is: why do organisms grow fast and achieve smaller sizes under more favourable conditions (= relatively higher temperature), while they grow longer and achieve larger sizes under less favourable conditions (relatively lower temperature), if larger size means higher fitness, while longer development may be risky? This evolutionary conundrum still awaits an ultimate explanation (Angilletta Jr et al. 2004; Angilletta and Dunham 2003; Verberk et al. 2021). Although theoretical modelling has shown that such a growth pattern can be achieved as a response to temperature alone, with a specific combination of energetic parameters and external mortality (Kozłowski et al. 2004), it has been suggested that other temperature-dependent environmental variables may be the actual drivers of this pattern. One of the most frequently invoked variable is the relative oxygen availability in the environment (e.g., Atkinson et al. 2006; Audzijonyte et al. 2019; Verberk et al. 2021; Woods 1999), which decreases with temperature increase. Importantly, this effect is more pronounced in aquatic systems (Forster et al. 2012). However, other temperature-dependent parameters are also being examined in the context of their possible effect on TSR induction and strength. Food availability is among the interfering factors in this regard. In aquatic systems, nutritional conditions are generally better at higher temperature, while a range of relatively mild thermal conditions is considered. However, there are no conclusive results so far on how nutritional conditions affect the plastic body size response to acute temperature changes. A study by Bazin et al. (2023) examined this particular issue, the effects of food and temperature on TSR, in medaka fish. An important value of the study was to relate the patterns found to fitness. This is a rare and highly desirable approach since evolutionary significance of any results cannot be reliably interpreted unless shown as expressed in light of fitness. The authors compared the body size of fish kept at 20°C and 30°C under conditions of food abundance or food restriction. The results showed that the TSR (smaller body size at 30°C compared to 20°C) was observed in both food treatments, but the effect was delayed during fish development under food restriction. Regarding the relevance to fitness, increased temperature resulted in more eggs laid but higher mortality, while food restriction increased survival but decreased the number of eggs laid in both thermal treatments. Overall, food restriction seemed to have a more severe effect on development at 20°C than at 30°C, contrary to the authors’ expectations. I found this result particularly interesting. One possible interpretation, also suggested by the authors, is that the relative oxygen availability, which was not controlled for in this study, could have affected this pattern. According to theoretical predictions confirmed in quite many empirical studies so far, oxygen restriction is more severe at higher temperatures. Perhaps for these particular two thermal treatments and in the case of the particular species studied, this restriction was more severe for organismal performance than the food restriction. This result is an example that all three variables, temperature, food and oxygen, should be taken into account in future studies if the interrelationship between them is to be understood in the context of TSR. It also shows that the reasons for growing smaller in warm may be different from those for growing larger in cold, as suggested, directly or indirectly, in some previous studies (Hessen et al. 2010; Leiva et al. 2019). Since medaka fish represent predatory vertebrates, the results of the study contribute to the issue of global warming effect on food webs, as the authors rightly point out. This is an important issue because the general decrease in the size or organisms in the aquatic environment with global warming is a fact (e.g., Daufresne et al. 2009), while the question of how this might affect entire communities is not trivial to resolve (Ohlberger 2013). REFERENCES Angilletta Jr, M. J., T. D. Steury & M. W. Sears, 2004. Temperature, growth rate, and body size in ectotherms: fitting pieces of a life–history puzzle. Integrative and Comparative Biology 44:498-509. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.498 Angilletta, M. J. & A. E. Dunham, 2003. The temperature-size rule in ectotherms: Simple evolutionary explanations may not be general. American Naturalist 162(3):332-342. https://doi.org/10.1086/377187 Atkinson, D., 1994. Temperature and organism size – a biological law for ectotherms. Advances in Ecological Research 25:1-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2504(08)60212-3 Atkinson, D., S. A. Morley & R. N. Hughes, 2006. From cells to colonies: at what levels of body organization does the 'temperature-size rule' apply? Evolution & Development 8(2):202-214 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-142X.2006.00090.x Audzijonyte, A., D. R. Barneche, A. R. Baudron, J. Belmaker, T. D. Clark, C. T. Marshall, J. R. Morrongiello & I. van Rijn, 2019. Is oxygen limitation in warming waters a valid mechanism to explain decreased body sizes in aquatic ectotherms? Global Ecology and Biogeography 28(2):64-77 https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12847 Bazin, S., Hemmer-Brepson, C., Logez, M., Sentis, A. & Daufresne, M. 2023. Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms. HAL, ver.3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03738584v3 Berrigan, D. & E. L. Charnov, 1994. Reaction norms for age and size at maturity in response to temperature – a puzzle for life historians. Oikos 70:474-478. https://doi.org/10.2307/3545787 Daufresne, M., K. Lengfellner & U. Sommer, 2009. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106(31):12788-93 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902080106 Forster, J., A. G. Hirst & D. Atkinson, 2012. Warming-induced reductions in body size are greater in aquatic than terrestrial species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(47):19310-19314. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1210460109 Hessen, D. O., P. D. Jeyasingh, M. Neiman & L. J. Weider, 2010. Genome streamlining and the elemental costs of growth. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25(2):75-80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.08.004 Kozłowski, J., M. Czarnoleski & M. Dańko, 2004. Can optimal resource allocation models explain why ectotherms grow larger in cold? Integrative and Comparative Biology 44(6):480-493. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/44.6.480 Leiva, F. P., P. Calosi & W. C. E. P. Verberk, 2019. Scaling of thermal tolerance with body mass and genome size in ectotherms: a comparison between water- and air-breathers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374:20190035. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2019.0035 Ohlberger, J., 2013. Climate warming and ectotherm body szie - from individual physiology to community ecology. Functional Ecology 27:991-1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12098 Verberk, W. C. E. P., D. Atkinson, K. N. Hoefnagel, A. G. Hirst, C. R. Horne & H. Siepel, 2021. Shrinking body sizes in response to warming: explanations for the temperature-size rule with special emphasis on the role of oxygen. Biological Reviews 96:247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12653 Woods, H. A., 1999. Egg-mass size and cell size: effects of temperature on oxygen distribution. American Zoologist 39:244-252. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/39.2.244 | Distinct impacts of food restriction and warming on life history traits affect population fitness in vertebrate ectotherms | Simon Bazin, Claire Hemmer-Brepson, Maxime Logez, Arnaud Sentis, Martin Daufresne | <p>The reduction of body size with warming has been proposed as the third universal response to global warming, besides geographical and phenological shifts. Observed body size shifts in ectotherms are mostly attributed to the temperature size rul... |  | Climate change, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2022-07-27 09:28:29 | View | |

06 Dec 2019

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslandsNatasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2543768The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradientRecommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure. References [1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press. | Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands | Natasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol | <p>For plant-pollinator interactions to occur, the flowering of plants and the flying period of pollinators (i.e. their phenologies) have to overlap. Yet, few models make use of this principle to predict interactions and fewer still are able to co... |  | Interaction networks, Pollination, Statistical ecology | Anna Eklöf | 2019-01-18 19:02:13 | View | |

06 Oct 2020

Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range?Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gspaceuse.htmlExplore and move: a key to success in a changing world?Recommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Joe Nocera, Marion Nicolaus and Laure CauchardChanges in the spatial range of many species are one of the major consequences of the profound alteration of environmental conditions due to human activities. Some species expand, sometimes spectacularly during invasions; others decline; some shift. Because these changes result in local biodiversity loss (whether local species go extinct or are replaced by colonizing ones), understanding the factors driving spatial range dynamics appears crucial to predict biodiversity dynamics. Identifying the factors that shape individual movement is a main step towards such understanding. The study described in this preregistration (McCune et al. 2020) falls within this context by testing possible links between individual exploration behaviour and movements related to daily space use in an avian study model currently rapidly expanding, the great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus). Movement and exploration: which direction(s) for the link between exploration and dispersal? Evolutionary and conservation perspectives References Badayev, A. V., Martin, T. E and Etges, W. J. 1996. Habitat sampling and habitat selection by female wild turkeys: ecological correlates and reproductive consequences. Auk 113: 636-646. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/4088984 | Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range? | Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) are rapidly expanding their geographic range (Wehtje 2003). Range expansion could be facilitated by consistent behavioural differences between individuals on the range edge and those in other parts of th... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Blandine Doligez | 2019-09-30 19:27:40 | View | |

31 Jan 2019

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesAaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_causal.htmlFrom cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroecological patternsRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the distribution of species on earth is one of the fundamental challenges in ecology and evolution. For a long time, this challenge has mainly been addressed from a correlative point of view with a focus on abiotic factors determining a species abiotic niche (classical bioenvelope models; [1]). It is only recently that researchers have realized that behaviour and especially plasticity in behaviour may play a central role in determining species ranges and their dynamics [e.g., 2-5]. Blaisdell et al. propose to take this even one step further and to analyse how behavioural flexibility and possibly associated causal cognition impacts range dynamics. References | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan | This PREREGISTRATION has undergone one round of peer reviews. We have now revised the preregistration and addressed reviewer comments. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2018-08-20 11:09:48 | View | ||

30 Mar 2021

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesBlaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6sFrom cognition to range dynamics – and from preregistration to peer-reviewed preprintRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by Laure Cauchard and 1 anonymous reviewerIn 2018 Blaisdell and colleagues set out to study how causal cognition may impact large scale macroecological patterns, more specifically range dynamics, in the great-tailed grackle (Fronhofer 2019). This line of research is at the forefront of current thought in macroecology, a field that has started to recognize the importance of animal behaviour more generally (see e.g. Keith and Bull (2017)). Importantly, the authors were pioneering the use of preregistrations in ecology and evolution with the aim of improving the quality of academic research. Now, nearly 3 years later, it is thanks to their endeavour of making research better that we learn that the authors are “[...] unable to speculate about the potential role of causal cognition in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range.” (Blaisdell et al. 2021; page 2). Is this a success or a failure? Every reader will have to find an answer to this question individually and there will certainly be variation in these answers as becomes clear from the referees’ comments. In my opinion, this is a success story of a more stringent and transparent approach to doing research which will help us move forward, both methodologically and conceptually. References Fronhofer (2019) From cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroe- Keith, S. A. and Bull, J. W. (2017) Animal culture impacts species' capacity to realise climate-driven range shifts. Ecography, 40: 296-304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02481 Blaisdell, A., Seitz, B., Rowney, C., Folsom, M., MacPherson, M., Deffner, D., and Logan, C. J. (2021) Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles. PsyArXiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6s | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Blaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ | <p>Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geo... | Preregistrations | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-11-27 09:49:55 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle