Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

29 Jan 2020

Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stabilityArnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya https://doi.org/10.1101/589895On the importance of stoichiometric constraints for understanding global change effects on food web dynamicsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe constraints associated with the mass balance of chemical elements (i.e. stoichiometric constraints) are critical to our understanding of ecological interactions, as outlined by the ecological stoichiometry theory [1]. Species in ecosystems differ in their elemental composition as well as in their level of elemental homeostasis [2], which can determine the outcome of interactions such as herbivory or decomposition on species coexistence and ecosystem functioning [3, 4]. References [1] Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J. (2017). Ecological Stoichiometry, The Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. doi: 10.1515/9781400885695 | Stoichiometric constraints modulate the effects of temperature and nutrients on biomass distribution and community stability | Arnaud Sentis, Bart Haegeman, and José M. Montoya | <p>Temperature and nutrients are two of the most important drivers of global change. Both can modify the elemental composition (i.e. stoichiometry) of primary producers and consumers. Yet their combined effect on the stoichiometry, dynamics, and s... |  | Climate change, Community ecology, Food webs, Theoretical ecology, Thermal ecology | Elisa Thebault | 2019-08-08 12:20:08 | View | |

21 Oct 2020

Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate changeJames Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.26.117200Uncertain predictions of species responses to perturbations lead to underestimate changes at ecosystem level in diverse systemsRecommended by Elisa Thebault based on reviews by Carlos Melian and 1 anonymous reviewerDifferent sources of uncertainty are known to affect our ability to predict ecological dynamics (Petchey et al. 2015). However, the consequences of uncertainty on prediction biases have been less investigated, especially when predictions are scaled up to higher levels of organisation as is commonly done in ecology for instance. The study of Orr et al. (2020) addresses this issue. It shows that, in complex systems, the uncertainty of unbiased predictions at a lower level of organisation (e.g. species level) leads to a bias towards underestimation of change at higher level of organisation (e.g. ecosystem level). This bias is strengthened by larger uncertainty and by higher dimensionality of the system. References Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, Kinzig AP, Daily GC, Loreau M, Grace JB, Larigauderie A, Srivastava DS, Naeem S (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature, 486, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148 | Why scaling up uncertain predictions to higher levels of organisation will underestimate change | James Orr, Jeremy Piggott, Andrew Jackson, Jean-François Arnoldi | <p>Uncertainty is an irreducible part of predictive science, causing us to over- or underestimate the magnitude of change that a system of interest will face. In a reductionist approach, we may use predictions at the level of individual system com... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Theoretical ecology | Elisa Thebault | Anonymous | 2020-06-02 15:41:12 | View |

26 May 2021

Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunitiesCamille Saade, Sonia Kéfi, Claire Gougat-Barbera, Benjamin Rosenbaum, and Emanuel A. Fronhofer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.03.409524Unity makes strength: clustered extinctions have stronger, longer-lasting effects on metacommunities dynamicsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Frederik De LaenderIn this article, Saade et al. (2021) investigate how the rate of local extinctions and their spatial distribution affect recolonization dynamics in metacommunities. They use an elegant combination of microcosm experiments with metacommunities of freshwater ciliates and mathematical modelling mirroring their experimental system. Their main findings are (i) that local patch extinctions increase both local (α-) and inter-patch (β-) diversity in a transient way during the recolonization process, (ii) that these effects depend more on the spatial distribution of extinctions (dispersed or clustered) than on their amount, and (iii) that they may spread regionally. A major strength of this study is that it highlights the importance of considering the spatial structure explicitly. Recent work on ecological networks has shown repeatedly that network structure affects the propagation of pathogens (Badham and Stocker 2010), invaders (Morel-Journel et al. 2019), or perturbation events (Gilarranz et al. 2017). Here, the spatial structure of the metacommunity is a regular grid of patches, but the distribution of extinction events may be either regularly dispersed (i.e., extinct patches are distributed evenly over the grid and are all surrounded by non-extinct patches only) or clustered (all extinct patches are neighbours). This has a direct effect on the neighbourhood of perturbed patches, and because perturbations have mostly local effects, their recovery dynamics are dominated by the composition of this immediate neighbourhood. In landscapes with dispersed extinctions, the neighbourhood of a perturbed patch is not affected by the amount of extinctions, and neither is its recovery time. In contrast, in landscapes with clustered extinctions, the amount of extinctions affects the depth of the perturbed area, which takes longer to recover when it is larger. Interestingly, the spatial distribution of extinctions here is functionally equivalent to differences in connectivity between perturbed and unperturbed patches, which results in contrasted “rescue recovery” and “mixing recovery” regimes as described by Zelnick et al. (2019).

Levins R (1969) Some Demographic and Genetic Consequences of Environmental Heterogeneity for Biological Control1. Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America, 15, 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/besa/15.3.237 Ruokolainen L (2013) Spatio-Temporal Environmental Correlation and Population Variability in Simple Metacommunities. PLOS ONE, 8, e72325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072325 Saade C, Kefi S, Gougat-Barbera C, Rosenbaum B, Fronhofer EA (2021) Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunities. bioRxiv, 2020.12.03.409524, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.03.409524 | Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunities | Camille Saade, Sonia Kéfi, Claire Gougat-Barbera, Benjamin Rosenbaum, and Emanuel A. Fronhofer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human activities lead more and more to the disturbance of plant and animal communities with local extinctions as a consequence. While these negative effects are clearly visible at a local scale, it is less clear how... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Elodie Vercken | 2020-12-08 15:55:20 | View | |

06 May 2022

Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in TunisiaAsma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665Even the current climate change winners could end up being losersRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Matt Hill, Philippe Louapre, José Hodar and Corentin IltisClimate change is accelerating (IPCC 2022), and so applies ever stronger selective pressures on biodiversity (Segan et al. 2016). Possible responses include range shifts or adaptations to new climatic conditions (Bellard et al. 2012), but there is still much uncertainty about the extent of most species' adaptive capacities and the impact of extreme climatic events. Battisti A, Stastny M, Netherer S, Robinet C, Schopf A, Roques A, Larsson S (2005) Expansion of Geographic Range in the Pine Processionary Moth Caused by Increased Winter Temperatures. Ecological Applications, 15, 2084–2096. https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1903 Bellard C, Bertelsmeier C, Leadley P, Thuiller W, Courchamp F (2012) Impacts of climate change on the future of biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 15, 365–377. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01736.x Bourougaaoui A, Ben Jamâa ML, Robinet C (2021) Has North Africa turned too warm for a Mediterranean forest pest because of climate change? Climatic Change, 165, 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-021-03077-1 Bourougaaoui A, Robinet C, Jamaa MLB, Laparie M (2022) Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia. bioRxiv, 2021.08.17.456665, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.08.17.456665 IPCC. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. In Press. Segan DB, Murray KA, Watson JEM (2016) A global assessment of current and future biodiversity vulnerability to habitat loss–climate change interactions. Global Ecology and Conservation, 5, 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2015.11.002 Verner D (2013) Tunisia in a Changing Climate : Assessment and Actions for Increased Resilience and Development. World Bank, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-9857-9 | Effects of climate warming on the pine processionary moth at the southern edge of its range: a retrospective analysis on egg survival in Tunisia | Asma Bourougaaoui, Christelle Robinet, Mohamed Lahbib Ben Jamâa, Mathieu Laparie | <p style="text-align: justify;">In recent years, ectotherm species have largely been impacted by extreme climate events, essentially heatwaves. In Tunisia, the pine processionary moth (PPM), <em>Thaumetopoea pityocampa</em>, is a highly damaging p... |  | Climate change, Dispersal & Migration, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology, Thermal ecology, Zoology | Elodie Vercken | 2021-08-19 11:03:13 | View | |

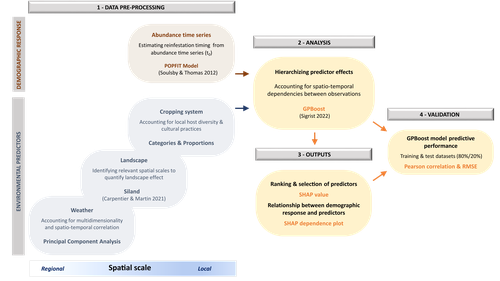

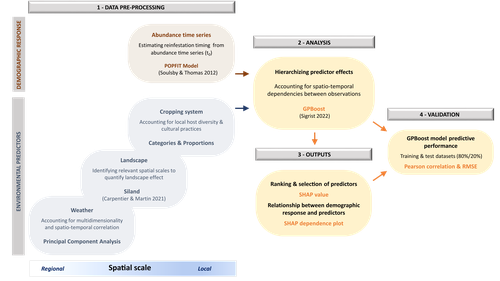

14 Jun 2024

Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of Bactrocera dorsalis population growth in Senegalese orchardsCécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.10.566583Uncovering the ecology in big-data by hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effectsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Jianqiang SunAlong with the generalization of open-access practices, large, heterogeneous datasets are becoming increasingly available to ecologists (Farley et al. 2018). While such data offer exciting opportunities for unveiling original patterns and trends, they also raise new challenges regarding how to extract relevant information and actually improve our knowledge of complex ecological systems, beyond purely descriptive correlations (Dietze 2017, Farley et al. 2018). In this work, Caumette et al. (2024) develop an original ecoinformatics approach to relate multi-scale environmental factors to the temporal dynamics of a major pest in mango orchards. Their method relies on the recent tree-boosting method GPBoost (Sigrist 2022) to hierarchize the influence of environmental factors of heterogeneous nature (e.g., orchard composition and management; landscape structure; climate) on the emergence date of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. As boosting methods allows the analysis of high-dimensional data, they are particularly adapted to the exploration of such datasets, to uncover unexpected, potentially complex dependencies between ecological dynamics and multiple environmental factors (Farley et al. 2018). In this article, Caumette et al. (2024) make a special effort to guide the reader step by step through their complex analysis pipeline to make it broadly understandable to the average ecologist, which is no small feat. I particularly welcome this commitment, as making new, cutting-edge analytical methods accessible to a large community of science practitioners with varying degrees of statistical or programming expertise is a major challenge for the future of quantitative ecology. The main result of Caumette et al. (2024) is that temperature and humidity conditions both at the local and regional scales are the main predictors of B. dorsalis emergence date, while orchard management practices seem to have relatively little influence. This suggests that favourable climatic conditions may allow the persistence of small populations of B. dorsalis over the dry season, which may then act as a propagule source for early re-infestations. However, as the authors explain, the resulting regression model is not designed for predictive purposes and should not at this stage be used for decision-making in pest management. Its main interest rather resides in identifying potential key factors favoring early infestations of B. dorsalis, and help focusing future experimental field studies on the most relevant levers for integrated pest management in mango orchards. In a wider perspective, this work also provides a convincing proof-of-concept for the use of boosting methods to identify the most influential factors in large, multivariate datasets in a variety of ecological systems. It is also crucial to keep in mind that the current exponential growth in high-throughput environmental data (Lucivero 2020) could quickly come into conflict with the need to reduce the environmental footprint of research (Mariette et al. 2022). In this context, robust and accessible methods for extracting and exploiting all the information available in already existing datasets might prove essential to a sustainable pursuit of science. References Dietze MC. 2017. Ecological Forecasting. Princeton University Press Mariette J, Blanchard O, Berné O, Aumont O, Carrey J, Ligozat A-L, Lellouch E, Roche P-E, Guennebaud G, Thanwerdas J, Bardou P, Salin G, Maigne E, Servan S, Ben-Ari T 2022. An open-source tool to assess the carbon footprint of research. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ac84a4 | Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of *Bactrocera dorsalis* population growth in Senegalese orchards | Cécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier | <p>Implementing integrated pest management programs to limit agricultural pest damage requires an understanding of the interactions between the environmental variability and population demographic processes. However, identifying key environmental ... |  | Demography, Landscape ecology, Statistical ecology | Elodie Vercken | 2023-12-11 17:02:08 | View | |

31 Jan 2019

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesAaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_causal.htmlFrom cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroecological patternsRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding the distribution of species on earth is one of the fundamental challenges in ecology and evolution. For a long time, this challenge has mainly been addressed from a correlative point of view with a focus on abiotic factors determining a species abiotic niche (classical bioenvelope models; [1]). It is only recently that researchers have realized that behaviour and especially plasticity in behaviour may play a central role in determining species ranges and their dynamics [e.g., 2-5]. Blaisdell et al. propose to take this even one step further and to analyse how behavioural flexibility and possibly associated causal cognition impacts range dynamics. References | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Kelsey McCune, Corina Logan | This PREREGISTRATION has undergone one round of peer reviews. We have now revised the preregistration and addressed reviewer comments. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2018-08-20 11:09:48 | View | ||

13 Mar 2021

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalSevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6behDispersal: from “neutral” to a state- and context-dependent viewRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTraditionally, dispersal has often been seen as “random” or “neutral” as Lowe & McPeek (2014) have put it. This simplistic view is likely due to dispersal being intrinsically difficult to measure empirically as well as “random” dispersal being a convenient simplifying assumption in theoretical work. Clobert et al. (2009), and many others, have highlighted how misleading this assumption is. Rather, dispersal seems to be usually a complex reaction norm, depending both on internal as well as external factors. One such internal factor is the sex of the dispersing individual. A recent review of the theoretical literature (Li & Kokko 2019) shows that while ideas explaining sex-biased dispersal go back over 40 years this state-dependency of dispersal is far from comprehensively understood. Sevchik et al. (2021) tackle this challenge empirically in a bird species, the great-tailed grackle. In contrast to most bird species, where females disperse more than males, the authors report genetic evidence indicating male-biased dispersal. The authors argue that this difference can be explained by the great-tailed grackle’s social and mating-system. Dispersal is a central life-history trait (Bonte & Dahirel 2017) with major consequences for ecological and evolutionary processes and patterns. Therefore, studies like Sevchik et al. (2021) are valuable contributions for advancing our understanding of spatial ecology and evolution. Importantly, Sevchik et al. also lead to way to a more open and reproducible science of ecology and evolution. The authors are among the pioneers of preregistering research in their field and their way of doing research should serve as a model for others. References Bonte, D. & Dahirel, M. (2017) Dispersal: a central and independent trait in life history. Oikos 126: 472-479. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03801 Clobert, J., Le Galliard, J. F., Cote, J., Meylan, S. & Massot, M. (2009) Informed dispersal, heterogeneity in animal dispersal syndromes and the dynamics of spatially structured populations. Ecol. Lett.: 12, 197-209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01267.x Li, X.-Y. & Kokko, H. (2019) Sex-biased dispersal: a review of the theory. Biol. Rev. 94: 721-736. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12475 Lowe, W. H. & McPeek, M. A. (2014) Is dispersal neutral? Trends Ecol. Evol. 29: 444-450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.05.009 Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. & Lukas, D. (2021) Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. EcoEvoRxiv, osf.io/t6beh, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6beh | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D | <p>In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain closer to the place they hatched for their entire lives. Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have focused on the resource-defense ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-08-24 17:53:06 | View | |

30 Mar 2021

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesBlaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6sFrom cognition to range dynamics – and from preregistration to peer-reviewed preprintRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by Laure Cauchard and 1 anonymous reviewerIn 2018 Blaisdell and colleagues set out to study how causal cognition may impact large scale macroecological patterns, more specifically range dynamics, in the great-tailed grackle (Fronhofer 2019). This line of research is at the forefront of current thought in macroecology, a field that has started to recognize the importance of animal behaviour more generally (see e.g. Keith and Bull (2017)). Importantly, the authors were pioneering the use of preregistrations in ecology and evolution with the aim of improving the quality of academic research. Now, nearly 3 years later, it is thanks to their endeavour of making research better that we learn that the authors are “[...] unable to speculate about the potential role of causal cognition in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range.” (Blaisdell et al. 2021; page 2). Is this a success or a failure? Every reader will have to find an answer to this question individually and there will certainly be variation in these answers as becomes clear from the referees’ comments. In my opinion, this is a success story of a more stringent and transparent approach to doing research which will help us move forward, both methodologically and conceptually. References Fronhofer (2019) From cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroe- Keith, S. A. and Bull, J. W. (2017) Animal culture impacts species' capacity to realise climate-driven range shifts. Ecography, 40: 296-304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02481 Blaisdell, A., Seitz, B., Rowney, C., Folsom, M., MacPherson, M., Deffner, D., and Logan, C. J. (2021) Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles. PsyArXiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6s | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Blaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ | <p>Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geo... | Preregistrations | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-11-27 09:49:55 | View | ||

31 Oct 2022

Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing dataAdam L. Mahood, Maxwell Benjamin Joseph, Anna Spiers, Michael J. Koontz, Nayani Ilangakoon, Kylen Solvik, Nathan Quarderer, Joe McGlinchy, Victoria Scholl, Lise St. Denis, Chelsea Nagy, Anna Braswell, Matthew W. Rossi, Lauren Herwehe, Leah wasser, Megan Elizabeth Cattau, Virginia Iglesias, Fangfang Yao, Stefan Leyk, Jennifer Balch https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/kehqzPreventing misuse of high-resolution remote sensing dataRecommended by Eric Goberville based on reviews by Jane Wyngaard and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jane Wyngaard and 1 anonymous reviewer

To observe, characterise, identify, understand, predict... This is the approach that researchers follow every day. This sequence is tirelessly repeated as the biological model, the targeted ecosystem and/or the experimental, environmental or modelling conditions change. This way of proceeding is essential in a world of rapid change in response to the frenetic pace of intensifying pressures and forcings that impact ecosystems. To better understand our Earth and the dynamics of its components, to map ecosystems and diversity patterns, and to identify changes, humanity had to demonstrate inventiveness and defy gravity. Gustave Hermite and Georges Besançon were the first to launch aloft balloons equipped with radio transmitters, making possible the transmission of meteorological data to observers in real time [1]. The development of aviation in the middle of the 20th century constituted a real leap forward for the frequent acquisition of aerial observations, leading to a significant improvement in weather forecasting models. The need for systematic collection of data as holistic as possible – an essential component for the observation of complex biological systems - has resulted in pushing the limits of technological prowess. The conquest of space and the concurrent development of satellite observations has largely contributed to the collection of a considerable mass of data, placing our Earth under the "macroscope" - a concept introduced to ecology in the early 1970s by Howard T. Odum (see [2]), and therefore allowing researchers to move towards a better understanding of ecological systems, deterministic and stochastic patterns … with the ultimate goal of improving management actions [2,3]. Satellite observations have been carried out for nearly five decades now [3] and have greatly contributed to a better qualitative and quantitative understanding of the functioning of our planet, its diversity, its climate... and to a better anticipation of possible future changes (e.g., [4-7]). This access to rich and complex sources of information, for which both spatial and temporal resolutions are increasingly fine, results in the implementation of increasingly complex computation-based analyses, in order to meet the need for a better understanding of ecological mechanisms and processes, and their possible changes. Steven Levitt stated that "Data is one of the most powerful mechanisms for telling stories". This is so true … Data should not be used as a guide to thinking and a critical judgment at each stage of the data exploitation process should not be neglected. This is what Mahood et al. [8] rightly remind us in their article "Ten simple rules for working with high-resolution remote sensing data" in which they provide the fundamentals to consider when working with data of this nature, a still underutilized resource in several topics, such as conservation biology [3]. In this unconventional article, presented in a pedagogical way, the authors remind different generations of readers how satellite data should be handled and processed. The authors aim to make the readers aware of the most frequent pitfalls encouraging them to use data adapted to their original question, the most suitable tools/methods/procedures, to avoid methodological overkill, and to ensure both ethical use of data and transparency in the research process. While access to high-resolution data is increasingly easy thanks to the implementation of dedicated platforms [4], and because of the development of easy-to-use processing software and pipelines, it is important to take the time to recall some of the essential rules and guidelines for managing them, from new users with little or no experience who will find in this article the recommendations, resources and advice necessary to start exploiting remote sensing data, to more experienced researchers. References [1] Jeannet P, Philipona R, and Richner H (2016). 8 Swiss upper-air balloon soundings since 1902. In: Willemse S, Furger M (2016) From weather observations to atmospheric and climate sciences in Switzerland: Celebrating 100 years of the Swiss Society for Meteorology. vdf Hochschulverlag AG. [2] Odum HT (2007) Environment, Power, and Society for the Twenty-First Century: The Hierarchy of Energy. Columbia University Press. [3] Boyle SA, Kennedy CM, Torres J, Colman K, Pérez-Estigarribia PE, Sancha NU de la (2014) High-Resolution Satellite Imagery Is an Important yet Underutilized Resource in Conservation Biology. PLOS ONE, 9, e86908. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086908 [4] Le Traon P-Y, Antoine D, Bentamy A, Bonekamp H, Breivik LA, Chapron B, Corlett G, Dibarboure G, DiGiacomo P, Donlon C, Faugère Y, Font J, Girard-Ardhuin F, Gohin F, Johannessen JA, Kamachi M, Lagerloef G, Lambin J, Larnicol G, Le Borgne P, Leuliette E, Lindstrom E, Martin MJ, Maturi E, Miller L, Mingsen L, Morrow R, Reul N, Rio MH, Roquet H, Santoleri R, Wilkin J (2015) Use of satellite observations for operational oceanography: recent achievements and future prospects. Journal of Operational Oceanography, 8, s12–s27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1755876X.2015.1022050 [5] Turner W, Rondinini C, Pettorelli N, Mora B, Leidner AK, Szantoi Z, Buchanan G, Dech S, Dwyer J, Herold M, Koh LP, Leimgruber P, Taubenboeck H, Wegmann M, Wikelski M, Woodcock C (2015) Free and open-access satellite data are key to biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 182, 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.048 [6] Melet A, Teatini P, Le Cozannet G, Jamet C, Conversi A, Benveniste J, Almar R (2020) Earth Observations for Monitoring Marine Coastal Hazards and Their Drivers. Surveys in Geophysics, 41, 1489–1534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10712-020-09594-5 [7] Zhao Q, Yu L, Du Z, Peng D, Hao P, Zhang Y, Gong P (2022) An Overview of the Applications of Earth Observation Satellite Data: Impacts and Future Trends. Remote Sensing, 14, 1863. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs14081863 [8] Mahood AL, Joseph MB, Spiers A, Koontz MJ, Ilangakoon N, Solvik K, Quarderer N, McGlinchy J, Scholl V, Denis LS, Nagy C, Braswell A, Rossi MW, Herwehe L, Wasser L, Cattau ME, Iglesias V, Yao F, Leyk S, Balch J (2021) Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing data. OSFpreprints, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/kehqz | Ten simple rules for working with high resolution remote sensing data | Adam L. Mahood, Maxwell Benjamin Joseph, Anna Spiers, Michael J. Koontz, Nayani Ilangakoon, Kylen Solvik, Nathan Quarderer, Joe McGlinchy, Victoria Scholl, Lise St. Denis, Chelsea Nagy, Anna Braswell, Matthew W. Rossi, Lauren Herwehe, Leah wasser,... | <p>Researchers in Earth and environmental science can extract incredible value from high-resolution (sub-meter, sub-hourly or hyper-spectral) remote sensing data, but these data can be difficult to use. Correct, appropriate and competent use of su... |  | Biogeography, Landscape ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Eric Goberville | 2021-10-19 21:41:22 | View | |

03 Jan 2024

Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation : should we go fractal?Fabien Laroche https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.29.501974Spatial patterns and autocorrelation challenges in ecological conservationRecommended by Eric Goberville based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and Charles J Marsh based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and Charles J Marsh

“Pattern, like beauty, is to some extent in the eye of the beholder” (Grant 1977 in Wiens, 1989) Ecologists are immersed in unraveling the complex spatial patterns that govern species diversity, driven by both practical and theoretical imperatives (Rahbek, 2005; Wang et al., 2019). This dual focus necessitates a practical imperative for strategic biodiversity conservation, requiring a nuanced understanding of locations with peak species richness and dynamic shifts in species assemblages (Chase et al., 2020). Simultaneously, there is a theoretical interest in using diversity patterns as empirical testing grounds for theories explaining factors influencing diversity disparities and the associated increase in species turnover correlated with inter-site distance (Condit et al., 2002).

McGill (2010), in his paper "Matters of Scale", highlights the scale-dependent nature of ecology, aligning with the recognition that spatial autocorrelation is inherent in biogeographical data and often correlated with sample size (Rahbek, 2005). Spatial autocorrelation, often underestimated in ecological studies (Dormann, 2007), occurs when proximate locations exhibit similarities in ecological attributes (Tobler, 1970; Getis, 2010), introducing a latent bias that compromises the robustness of ecological findings (Dormann, 2007; Dormann et al., 2007). This phenomenon serves as both an asset, providing valuable information for inferring processes from patterns (Palma et al. 1999), and a challenge, imposing limitations on hypothesis testing and prediction (Dormann et al., 2007 and references therein). Various factors contribute to spatial autocorrelation, with three primary contributors (Dormann et al., 2007; Legendre, 1993; Legendre and Fortin, 1989; Legendre and Legendre, 2012): (i) distance-related effects in biological processes, (ii) misrepresentation of non-linear relationships between the environment and species as linear and (iii) the oversight of a crucial spatially structured environmental determinant in the statistical model, leading to spatial structuring in the response (Dormann et al., 2007).

Recognising the pivotal role of spatial heterogeneity in ecological theories (Wang et al., 2019), it becomes imperative to discern and address the limitations introduced by spatial autocorrelation (Legendre, 1993). McGill (2011) emphasises that the ultimate goal of biodiversity pattern studies should be to develop a quantitative predictive theory useful for conservation. The spatial dimension's importance in study planning, determining the system's scale, appropriate quadrat size, and spacing between sampling stations, is paramount (Fortin, 1999a,b). Responses to these considerations are intricately linked with study objectives and insights from pre-sampling campaigns, underscoring the need for a nuanced and rigorous approach (Delmelle, 2021).

Understanding statistical techniques and nested sampling designs is crucial to answering fundamental ecological questions (Dormann et al., 2007; McDonald, 2012). In addressing spatial autocorrelation challenges, ecologists must recognize the limitations of many standard statistical methods in ecological studies (Dale and Fortin, 2002; Legendre and Fortin, 1989; Steel et al., 2013). In the initial phases of description or hypothesis generation, ecologists should proactively acknowledge the spatial structure in their data and conduct tests for spatial autocorrelation (for a comprehensive description, see Legendre and Fortin, 1989): various tools, including correlograms, spectral analysis, the Mantel test, and clustering methods, facilitate the assessment and description of spatial structures. The partial Mantel test enables the study of causal models with space as an explanatory variable. Techniques for mapping ecological variables, such as interpolation, trend surface analysis, and constrained clustering, yield maps providing valuable insights into the spatial dynamics of ecological systems.

This refined consideration of spatial autocorrelation emerges as an imperative in ecological research, fostering a deeper and more precise understanding of the intricate interplay between species diversity, spatial patterns, and the inherent limitations imposed by spatial autocorrelation (Legendre et al., 2002). This not only contributes significantly to the scientific discourse in ecology but also aligns with McGill's vision of developing predictive theories for effective conservation (Bacaro et al., 2016; McGill, 2011).

In this study by Fabien Laroche (2023), titled “Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation: should we go fractal?” the primary focus was on addressing the challenges associated with estimating the autocorrelation range of species distribution across spatial scales. The study aimed to explore alternative sampling designs, with a particular focus on the application of fractal designs—self-similar designs with well-identified scales. The overarching goal was to evaluate whether fractal designs could offer a more efficient compromise compared to traditional hybrid designs, which involve mixing random sampling points with a systematic grid.

Virtual ecology provides a way to test whether sampling designs can accurately detect or quantify effects of interest before implementing them in the field. Beyond the question of assessing the power of empirical designs, a virtual ecology analysis contributes to clearly formulating the set of questions associated with a design. However, only a few virtual studies have focused on efficient designs to accurately estimate the autocorrelation range of biodiversity variables. In this study, the statistical framework of optimal design of experiments was employed—a methodology often used in building and comparing designs of temporal or spatiotemporal biodiversity surveys but rarely applied to the specific problem of quantifying spatial autocorrelation.

Key findings from the study shed light on optimal sampling strategies, with a notable dependence on the feasible grid mesh size over the study area in relation to expected autocorrelation range values. The results demonstrated that the efficiency of designs varied based on the specific effect under study. Fractal designs, however, exhibited superior performance, particularly when assessing the effect of a monotonic environmental gradient across space.

In conclusion, the study provides valuable insights into the potential benefits of incorporating fractal designs in biodiversity studies, offering a nuanced and efficient approach to estimate spatial autocorrelation. These findings contribute significantly to the ongoing scientific discourse in ecology, providing practical considerations for improving sampling designs in biodiversity assessments.

References

Bacaro, G., Altobelli, A., Cameletti, M., Ciccarelli, D., Martellos, S., Palmer, M.W., Ricotta, C., Rocchini, D., Scheiner, S.M., Tordoni, E., Chiarucci, A., 2016. Incorporating spatial autocorrelation in rarefaction methods: Implications for ecologists and conservation biologists. Ecological Indicators 69, 233-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2016.04.026

Chase, J.M., Jeliazkov, A., Ladouceur, E., Viana, D.S., 2020. Biodiversity conservation through the lens of metacommunity ecology. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1469, 86-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14378

Condit, R., Pitman, N., Leigh, E.G., Chave, J., Terborgh, J., Foster, R.B., Núñez, P., Aguilar, S., Valencia, R., Villa, G., Muller-Landau, H.C., Losos, E., Hubbell, S.P., 2002. Beta-Diversity in Tropical Forest Trees. Science 295, 666-669. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1066854

Dale, M.R.T., Fortin, M.-J., 2002. Spatial autocorrelation and statistical tests in ecology. Écoscience 9, 162-167. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.2002.11682702

Delmelle, E.M., 2021. Spatial Sampling, in: Fischer, M.M., Nijkamp, P. (Eds.), Handbook of Regional Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1829-1844.

Dormann, C.F., 2007. Effects of incorporating spatial autocorrelation into the analysis of species distribution data. Global Ecology & Biogeography 16, 129-128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00279.x

Dormann, C.F., McPherson, J.M., Araújo, M.B., Bivand, R., Bolliger, J., Carl, G., Davies, R.G., Hirzel, A., Jetz, W., Kissling, W.D., Kühn, I., Ohlemüler, R., Peres-Neto, P.R., Reineking, B., Schröder, B., Schurr, F.M., Wilson, R., 2007. Methods to account for spatial autocorrelation in the analysis of species distributional data: a review. Ecography 33, 609-628. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05171.x

Fortin, M.-J., 1999a. Effects of quadrat size and data measurement on the detection of boundaries. Journal of Vegetation Science 10, 43-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3237159

Fortin, M.-J., 1999b. Effects of sampling unit resolution on the estimation of spatial autocorrelation. Écoscience 6, 636-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/11956860.1999.11682547

Getis, A., 2010. Spatial Autocorrelation, in: Fischer, M.M., Getis, A. (Eds.), Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 255-278.

Laroche, F., 2023. Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation: should we go fractal? bioRxiv, 2022.07.29.501974, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.29.501974

Legendre, P., 1993. Spatial Autocorrelation: Trouble or New Paradigm? Ecology 74, 1659-1673. https://doi.org/10.2307/1939924

Legendre, P., Dale, M.R.T., Fortin, M.-J., Gurevitch, J., Hohn, M., Myers, D., 2002. The consequences of spatial structure for the design and analysis of ecological field surveys. Ecography 25, 601-615. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0587.2002.250508.x

Legendre, P., Fortin, M.J., 1989. Spatial pattern and ecological analysis. Vegetatio 80, 107-138. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00048036

Legendre, P., Legendre, L., 2012. Numerical Ecology, Third Edition ed. Elsevier, The Netherlands.

McDonald, T., 2012. Spatial sampling designs for long-term ecological monitoring, in: Cooper, A.B., Gitzen, R.A., Licht, D.S., Millspaugh, J.J. (Eds.), Design and Analysis of Long-term Ecological Monitoring Studies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 101-125.

McGill, B.J., 2010. Matters of Scale. Science 328, 575-576. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188528

McGill, B.J., 2011. Linking biodiversity patterns by autocorrelated random sampling. American Journal of Botany 98, 481-502. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1000509

Rahbek, C., 2005. The role of spatial scale and the perception of large-scale species-richness patterns. Ecology Letters 8, 224-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00701.x

Steel, E.A., Kennedy, M.C., Cunningham, P.G., Stanovick, J.S., 2013. Applied statistics in ecology: common pitfalls and simple solutions. Ecosphere 4, art115. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES13-00160.1

Tobler, W.R., 1970. A Computer Movie Simulating Urban Growth in the Detroit Region. Economic Geography 46, 234-240. https://doi.org/10.2307/143141

Wang, S., Lamy, T., Hallett, L.M., Loreau, M., 2019. Stability and synchrony across ecological hierarchies in heterogeneous metacommunities: linking theory to data. Ecography 42, 1200-1211. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04290

Wiens, J.A., 1989. The ecology of bird communities. Cambridge University Press.

| Efficient sampling designs to assess biodiversity spatial autocorrelation : should we go fractal? | Fabien Laroche | <p>Quantifying the autocorrelation range of species distribution in space is necessary for applied ecological questions, like implementing protected area networks or monitoring programs. However, the power of spatial sampling designs to estimate t... |  | Biodiversity, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Statistical ecology | Eric Goberville | 2023-04-21 10:54:29 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle