Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

28 Dec 2022

Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouseCharlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512An experimental approach for understanding how terrestrial isopods respond to environmental stressorsRecommended by Aniruddha Belsare based on reviews by Aaron Yilmaz and Michael Morris based on reviews by Aaron Yilmaz and Michael Morris

In this article, the authors discuss the results of their study investigating the effects of heat stress and moisture stress on a terrestrial isopod Armadilldium vulgare, the common woodlouse [1]. Specifically, the authors have assessed how increased temperature or decreased moisture affects life history traits (such as growth, survival, and reproduction) as well as physiological traits (immune cell parameters and \( beta \)-galactosidase activity). This article quantitatively evaluates the effects of the two stressors on woodlouse. Terrestrial isopods like woodlouse are sensitive to thermal and moisture stress [2; 3] and are therefore good models to test hypotheses in global change biology and for monitoring ecosystem health. An important feature of this study is the combination of experimental, laboratory, and analytical techniques. Experiments were conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory by modulating temperature and moisture, life history and physiological traits were measured/analyzed and then tested using models. Both stressors had negative impacts on survival and reproduction of woodlouse, and result in premature ageing. Although thermal stress did not affect survival, it slowed woodlouse growth. Moisture stress did not have a detectable effect on woodlouse growth but decreased survival and reproductive success. An important insight from this study is that effects of heat and moisture stressors on woodlouse are not necessarily linear, and experimental approaches can be used to better elucidate the mechanisms and understand how these organisms respond to environmental stress. This article is timely given the increasing attention on biological monitoring and ecosystem health. References: [1] Depeux C, Branger A, Moulignier T, Moreau J, Lemaître J-F, Dechaume-Moncharmont F-X, Laverre T, Pauhlac H, Gaillard J-M, Beltran-Bech S (2022) Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse. bioRxiv, 2022.09.26.509512., ver. 3 peer-reviewd and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512 [2] Warburg MR, Linsenmair KE, Bercovitz K (1984) The effect of climate on the distribution and abundance of isopods. In: Sutton SL, Holdich DM, editors. The Biology of Terrestrial Isopods. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 339–367. [3] Hassall M, Helden A, Goldson A, Grant A (2005) Ecotypic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity in reproductive traits of Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda: Oniscidea). Oecologia 143: 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1772-3 | Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse | Charlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech | <p>We tested independently the influences of increasing temperature and decreasing moisture on life history and physiological traits in the arthropod <em>Armadillidium vulgare</em>. Both increasing temperature and decreasing moisture led individua... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Life history, Physiology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Aniruddha Belsare | 2022-09-28 13:13:47 | View | |

06 Dec 2019

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslandsNatasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2543768The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradientRecommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure. References [1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press. | Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands | Natasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol | <p>For plant-pollinator interactions to occur, the flowering of plants and the flying period of pollinators (i.e. their phenologies) have to overlap. Yet, few models make use of this principle to predict interactions and fewer still are able to co... |  | Interaction networks, Pollination, Statistical ecology | Anna Eklöf | 2019-01-18 19:02:13 | View | |

05 Apr 2022

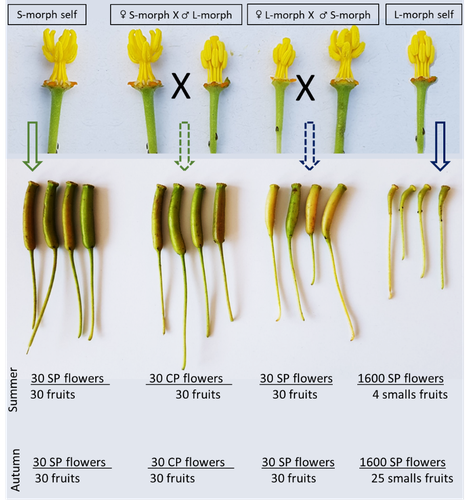

Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetalaLuis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457Water primerose (Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala) auto- and allogamy: an ecological perspectiveRecommended by Antoine Vernay based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewer

Invasive plant species are widely studied by the ecologist community, especially in wetlands. Indeed, alien plants are considered one of the major threats to wetland biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019). Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G.L.Nesom & Kartesz, 2000 (Lgh) is one of them and has received particular attention for a long time (Hieda et al., 2020; Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiebaut, 2013). The ecology of this invasive species and its effect on its biotic and abiotic environment has been studied in previous works. Different processes were demonstrated to explain their invasibility such as allelopathic interference (Dandelot et al., 2008), resource competition (Gérard et al., 2014), and high phenotypic plasticity (Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiébaut, 2013), to cite a few of them. However, although vegetative reproduction is a well-known invasive process for alien plants like Lgh (Glover et al., 2015), the sexual reproduction of this species is still unclear and may help to understand the Lgh population dynamics. Portillo Lemus et al. (2021) showed that two floral morphs of Lgh co-exist in natura, involving self-compatibility for short-styled phenotype and self-incompatibility for long-styled phenotype processes. This new article (Portillo Lemus et al., 2022) goes further and details the underlying mechanisms of the sexual reproduction of the two floral morphs. Complementing their previous study, the authors have described a late self-incompatible process associated with the long-styled morph, which authorized a small proportion of autogamy. Although this represents a small fraction of the L-morph reproduction, it may have a considerable impact on the L-morph population dynamics. Indeed, authors report that “floral morphs are mostly found in allopatric monomorphic populations (i.e., exclusively S-morph or exclusively L-morph populations)” with a large proportion of L-morph populations compared to S-morph populations in the field. It may seem counterintuitive as L-morph mainly relies on cross-fecundation. Results show that L-morph autogamy mainly occurs in the fall, late in the reproduction season. Therefore, the reproduction may be ensured if no exogenous pollen reaches the stigma of L-morph individuals. It partly explains the large proportion of L-morph populations in the field. Beyond the description of late-acting self-incompatibility, which makes the Onagraceae a third family of Myrtales with this reproductive adaptation, the study raises several ecological questions linked to the results presented in the article. First, it seems that even if autogamy is possible, Lgh would favour allogamy, even in S-morph, through the faster development of pollen tubes from other individuals. This may confer an adaptative and evolutive advantage for the Lgh, increasing its invasive potential. The article shows this faster pollen tube development in S-morph but does not test the evolutive consequences. It is an interesting perspective for future research. It would also be interesting to describe cellular processes which recognize and then influence the speed of the pollen tube. Second, the importance of sexual reproduction vs vegetative reproduction would also provide information on the benefits of sexual dimorphism within populations. For instance, how fruit production increases the dispersal potential of Lgh would help to understand Lgh population dynamics and to propose adapted management practices (Delbart et al., 2013; Meisler, 2009). To conclude, the study proposes a morphological, reproductive and physiological description of the Lgh sexual reproduction process. However, underlying ecological questions are well included in the article and the ecophysiological results enlighten some questions about the role of sexual reproduction in the invasiveness of Lgh. I advise the reader to pay attention to the reviewers’ comments; the debates were very constructive and, thanks to the great collaboration with the authorship, lead to an interesting paper about Lgh reproduction and with promising perspectives in ecology and invasion ecology. References Dandelot S, Robles C, Pech N, Cazaubon A, Verlaque R (2008) Allelopathic potential of two invasive alien Ludwigia spp. Aquatic Botany, 88, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.004 Delbart E, Mahy G, Monty A (2013) Efficacité des méthodes de lutte contre le développement de cinq espèces de plantes invasives amphibies : Crassula helmsii, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Ludwigia grandiflora, Ludwigia peploides et Myriophyllum aquaticum (synthèse bibliographique). BASE, 17, 87–102. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=9586 Gérard J, Brion N, Triest L (2014) Effect of water column phosphorus reduction on competitive outcome and traits of Ludwigia grandiflora and L. peploides, invasive species in Europe. Aquatic Invasions, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.04 Glover R, Drenovsky RE, Futrell CJ, Grewell BJ (2015) Clonal integration in Ludwigia hexapetala under different light regimes. Aquatic Botany, 122, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.01.004 Hieda S, Kaneko Y, Nakagawa M, Noma N (2020) Ludwigia grandiflora (Michx.) Greuter & Burdet subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G. L. Nesom & Kartesz, an Invasive Aquatic Plant in Lake Biwa, the Largest Lake in Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica, 71, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.201911 Meisler J (2009) Controlling Ludwigia hexaplata in Northern California. Wetland Science and Practice, 26, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1672/055.026.0404 Portillo Lemus LO, Harang M, Bozec M, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2022) Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heteromorphic invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala. bioRxiv, 2021.07.15.452457, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457 Portillo Lemus LO, Bozec M, Harang M, Coudreuse J, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2021) Self-incompatibility limits sexual reproduction rather than environmental conditions in an invasive water primrose. Plant-Environment Interactions, 2, 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10042 Reid AJ, Carlson AK, Creed IF, Eliason EJ, Gell PA, Johnson PTJ, Kidd KA, MacCormack TJ, Olden JD, Ormerod SJ, Smol JP, Taylor WW, Tockner K, Vermaire JC, Dudgeon D, Cooke SJ (2019) Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews, 94, 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12480 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G (2013) A success story: water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 23, 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387 Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiébaut G (2013) Seasonal plasticity of Ludwigia grandiflora under light and water depth gradients: An outdoor mesocosm experiment. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 208, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.004 | Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala | Luis O. Portillo Lemus, Maryline Harang, Michel Bozec, Jacques Haury, Solenn Stoeckel, Dominique Barloy | <p style="text-align: justify;">Breeding system influences local population genetic structure, effective size, offspring fitness and functional variation. Determining the respective importance of self- and cross-fertilization in hermaphroditic flo... |  | Biological invasions, Botany, Freshwater ecology, Pollination | Antoine Vernay | 2021-07-16 09:53:50 | View | |

26 Mar 2019

Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context?Corina Logan, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Kelsey McCune http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.htmlCan context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changesRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Andrea Griffin based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Andrea Griffin

Behavioral flexibility is a key for species adaptation to new environments. Predicting species responses to new contexts hence requires knowledge on the amount to and conditions in which behavior can be flexible. This is what Logan and collaborators propose to assess in a series of experiments on the great-tailed grackles, in a context of rapid range expansion. This pre-registration is integrated into this large research project and concerns more specifically the manipulability of the cognitive aspects of behavioral flexibility. Logan and collaborators will use reversal learning tests to test whether (i) behavioral flexibility is manipulatable, (ii) manipulating flexibility improves flexibility and problem solving in a new context, (iii) flexibility is repeatable within individuals, (iv) individuals are faster at problem solving as they progress through serial reversals. The pre-registration carefully details the hypotheses, their associated predictions and alternatives, and the plan of statistical analyses, including power tests. The ambitious program presented in this pre-registration has the potential to provide important pieces to better understand the mechanisms of species adaptability to new environments. | Is behavioral flexibility manipulatable and, if so, does it improve flexibility and problem solving in a new context? | Corina Logan, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Kelsey McCune | This is one of the first studies planned for our long-term research on the role of behavioral flexibility in rapid geographic range expansions. Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an impor... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2018-07-03 13:23:10 | View | ||

15 May 2023

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new contextLogan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xsAn experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativenessRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer

Whether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014). Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027 Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019) Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs | Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context | Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. Howev... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-01-13 19:08:52 | View | ||

26 May 2023

Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibilityMcCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59KDo reversal learning methods measure behavioral flexibility?Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh

Assessing the reliability of the methods we use in actually measuring the intended trait should be one of our first priorities when designing a study – especially when the trait in question is not directly observable and is measured through a proxy. This is the case for cognitive traits, which are often quantified through measures of behavioral performance. Behavioral flexibility is of particular interest in the context of great environmental changes that a lot of populations have to experiment. This type of behavioral performance is often measured through reversal learning experiments (Bond 2007). In these experiments, individuals first learn a preference, for example for an object of a certain type of form or color, associated with a reward such as food. The characteristics of the rewarded object then change, and the individuals hence have to learn these new characteristics (to get the reward). The time needed by the individual to make this change in preference has been considered a measure of behavioral flexibility. Although reversal learning experiments have been widely used, their construct validity to assess behavioral flexibility has not been thoroughly tested. This was the aim of McCune and collaborators' (2023) study, through the test of the repeatability of individual performance within and across contexts of reversal learning, in the great-tailed grackle. This manuscript presents a post-study of the preregistered study* (Logan et al. 2019) that was peer-reviewed and received an In Principle Recommendation for PCI Ecology (Coulon 2019; the initial preregistration was split into 3 post-studies).

The first hypothesis was tested by measuring the repeatability of the time needed by individuals to switch color preference in a color reversal learning task (colored tubes), over serial sessions of this task. The second one was tested by measuring the time needed by individuals to switch solutions, within 3 different contexts: (1) colored tubes, (2) plastic and (3) wooden multi-access boxes involving several ways to access food. Despite limited sample sizes, the results of these experiments suggest that there is both temporal and contextual repeatability of behavioral flexibility performance of great-tailed grackles, as measured by reversal learning experiments. Those results are a first indication of the construct validity of reversal learning experiments to assess behavioral flexibility. As highlighted by McCune and collaborators, it is now necessary to assess the discriminant validity of these experiments, i.e. checking that a different performance is obtained with tasks (experiments) that are supposed to measure different cognitive abilities. Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Logan, CJ, Lukas D, Bergeron L, Folsom M, & McCune, K. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In Principle Acceptance by PCI Ecology of the Version on 6 Aug 2019. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ (2023) Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59K | Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility | McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Research into animal cognitive abilities is increasing quickly and often uses methods where behavioral performance on a task is assumed to represent variation in the underlying cognitive trait. However, because thes... | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-08-15 20:56:42 | View | ||

19 Mar 2024

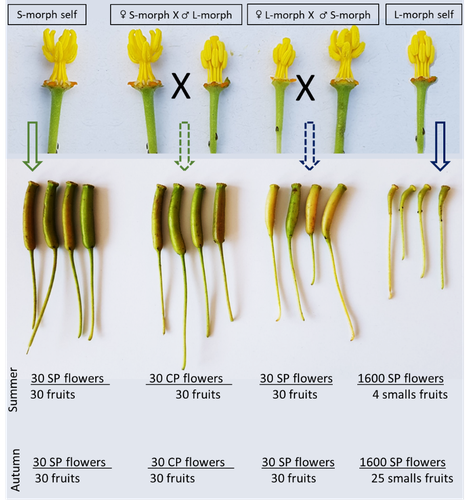

How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approachPaul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier https://doi.org/10.32942/X2JS41Gene flow in the city. Unravelling the mechanisms behind the variability in urbanization effects on genetic patterns.Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Worldwide, city expansion is happening at a fast rate and at the same time, urbanists are more and more required to make place for biodiversity. Choices have to be made regarding the area and spatial arrangement of suitable spaces for non-human living organisms, that will favor the long-term survival of their populations. To guide those choices, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms driving the effects of land management on biodiversity. Research results on the effects of urbanization on genetic diversity have been very diverse, with studies showing higher genetic diversity in rural than in urban populations (e.g. Delaney et al. 2010), the contrary (e.g. Miles et al. 2018) or no difference (e.g. Schoville et al. 2013). The same is true for studies investigating genetic differentiation. The reasons for these differences probably lie in the relative intensities of gene flow and genetic drift in each case study, which are hard to disentangle and quantify in empirical datasets. In their paper, Savary et al. (2024) used an elegant and powerful simulation approach to better understand the diversity of observed patterns and investigate the effects of dispersal limitation on genetic patterns (diversity and differentiation). Their simulations involved the landscapes of 325 real European cities, each under three different scenarios mimicking 3 virtual urban tolerant species with different abilities to move within cities while genetic drift intensity was held constant across scenarios. The cities were chosen so that the proportion of artificial areas was held constant (20%) but their location and shape varied. This design allowed the authors to investigate the effect of connectivity and spatial configuration of habitat on the genetic responses to spatial variations in dispersal in cities. The main results of this simulation study demonstrate that variations in dispersal spatial patterns, for a given level of genetic drift, trigger variations in genetic patterns. Genetic diversity was lower and genetic differentiation was larger when species had more difficulties to move through the more hostile components of the urban environment. The increase of the relative importance of drift over gene flow when dispersal was spatially more constrained was visible through the associated disappearance of the pattern of isolation by resistance. Forest patches (usually located at the periphery of the cities) usually exhibited larger genetic diversity and were less differentiated than urban green spaces. But interestingly, the presence of habitat patches at the interface between forest and urban green spaces lowered those differences through the promotion of gene flow. One other noticeable result, from a landscape genetic method point of view, is the fact that there might be a limit to the detection of barriers to genetic clusters through clustering analyses because of the increased relative effect of genetic drift. This result needs to be confirmed, though, as genetic structure has only been investigated with a recent approach based on spatial graphs. It would be interesting to also analyze those results with the usual Bayesian genetic clustering approaches. Overall, this study addresses an important scientific question about the mechanisms explaining the diversity of observed genetic patterns in cities. But it also provides timely cues for connectivity conservation and restoration applied to cities. Delaney, K. S., Riley, S. P., and Fisher, R. N. (2010). A rapid, strong, and convergent genetic response to urban habitat fragmentation in four divergent and widespread vertebrates. PLoS ONE, 5(9):e12767. | How does dispersal shape the genetic patterns of animal populations in European cities? A simulation approach | Paul Savary, Cécile Tannier, Jean-Christophe Foltête, Marc Bourgeois, Gilles Vuidel, Aurélie Khimoun, Hervé Moal, Stéphane Garnier | <p><em>Context and objectives</em></p> <p>Although urbanization is a major driver of biodiversity erosion, it does not affect all species equally. The neutral genetic structure of populations in a given species is affected by both genetic drift a... |  | Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Molecular ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Terrestrial ecology | Aurélie Coulon | 2023-07-25 19:09:16 | View | |

30 Jan 2020

Diapause is not selected as a bet-hedging strategy in insects: a meta-analysis of reaction norm shapesJens Joschinski and Dries Bonte 10.1101/752881When to diapause or not to diapause? Winter predictability is not the answerRecommended by Bastien Castagneyrol based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron, Md Habibur Rahman Salman and 1 anonymous reviewerWinter is a harsh season for many organisms that have to cope with food shortage and potentially lethal temperatures. Many species have evolved avoidance strategies. Among them, diapause is a resistance stage many insects use to overwinter. For an insect, it is critical to avoid lethal winter temperatures and thus to initiate diapause before winter comes, while making the most of autumn suitable climatic conditions [1,2]. Several cues can be used to appreciate that winter is coming, including day length and temperature [3]. But climate changes, temperatures rise and become more variable from year to year, which imposes strong pressure upon insect phenology [4]. How can insects adapt to changes in the mean and variance of winter onset? References [1] Dyck, H. V., Bonte, D., Puls, R., Gotthard, K., and Maes, D. (2015). The lost generation hypothesis: could climate change drive ectotherms into a developmental trap? Oikos, 124(1), 54–61. doi: 10.1111/oik.02066 | Diapause is not selected as a bet-hedging strategy in insects: a meta-analysis of reaction norm shapes | Jens Joschinski and Dries Bonte | Many organisms escape from lethal climatological conditions by entering a resistant resting stage called diapause, and it is essential that this strategy remains optimally timed with seasonal change. Climate change therefore exerts selection press... | Maternal effects, Meta-analyses, Phenotypic plasticity, Terrestrial ecology | Bastien Castagneyrol | 2019-09-20 11:47:47 | View | ||

02 Jan 2024

Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy modelsRahel Sollmann https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.08.552394Useful clarity on the value of considering temporal variability in detection probabilityRecommended by Benjamin Bolker based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine based on reviews by Dana Karelus and Ben Augustine

As so often quoted, "all models are wrong; more specifically, we always neglect potentially important factors in our models of ecological systems. We may neglect these factors because no-one has built a computational framework to include them; because including them would be computationally infeasible; or because we don't have enough data. When considering whether to include a particular process or form of heterogeneity, the gold standard is to fit models both with and without the component, and then see whether we needed the component in the first place -- that is, whether including that component leads to an important difference in our conclusions. However, this approach is both tedious and endless, because there are an infinite number of components that we could consider adding to any given model. Therefore, thoughtful exercises that evaluate the importance of particular complications under a realistic range of simulations and a representative set of case studies are extremely valuable for the field. While they cannot provide ironclad guarantees, they give researchers a general sense of when they can (probably) safely ignore some factors in their analyses. This paper by Sollmann (2024) shows that for a very wide range of scenarios, temporal and spatiotemporal variability in the probability of detection have little effect on the conclusions of spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models. The author is thoughtful about when such variability may be important, e.g. when variation in detection and density is correlated and thus confounded, or when variation is driven by animals' behavioural responses to being captured. | Mt or not Mt: Temporal variation in detection probability in spatial capture-recapture and occupancy models | Rahel Sollmann | <p>State variables such as abundance and occurrence of species are central to many questions in ecology and conservation, but our ability to detect and enumerate species is imperfect and often varies across space and time. Accounting for imperfect... |  | Euring Conference, Statistical ecology | Benjamin Bolker | Dana Karelus, Ben Augustine, Ben Augustine | 2023-08-10 09:18:56 | View |

12 Jun 2019

Environmental heterogeneity drives tsetse fly population dynamics and controlCecilia H, Arnoux S, Picault S, Dicko A, Seck MT, Sall B, Bassene M, Vreysen M, Pagabeleguem S, Bance A, Bouyer J, Ezanno P https://doi.org/10.1101/493650Modeling jointly landscape complexity and environmental heterogeneity to envision new strategies for tsetse flies controlRecommended by Benjamin Roche based on reviews by Timothée Vergne and 1 anonymous reviewerToday, understanding spatio-temporal dynamics of pathogens is pivotal to understand their transmission and controlling them. First, understanding this dynamics can reveal the ecology of their transmission [1]. Indeed, such knowledge, based on data that are quite easy to access, can shed light on transmission modes, which could rely on different animal species that can be spatially distributed in a non-uniform way [2]. This is especially true for pathogens with complex life-cycles, despite that investigating such dynamics is very challenging and rely mostly on mathematical models. References [1] Grenfell, B. T., Bjørnstad, O. N., & Kappey, J. (2001). Travelling waves and spatial hierarchies in measles epidemics. Nature, 414(6865), 716-723. doi: 10.1038/414716a | Environmental heterogeneity drives tsetse fly population dynamics and control | Cecilia H, Arnoux S, Picault S, Dicko A, Seck MT, Sall B, Bassene M, Vreysen M, Pagabeleguem S, Bance A, Bouyer J, Ezanno P | <p>A spatially and temporally heterogeneous environment may lead to unexpected population dynamics. Knowledge still is needed on which of the local environment properties favour population maintenance at larger scale. For pathogen vectors, such as... |  | Biological control, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Benjamin Roche | 2018-12-14 12:13:39 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle