Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▼ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

18 Apr 2024

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

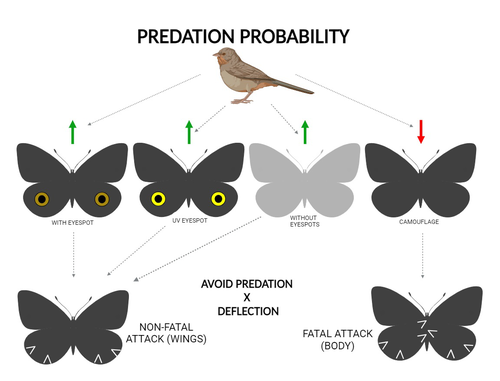

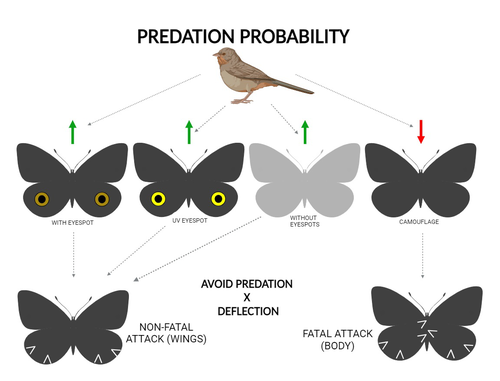

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

16 Nov 2020

Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functionsAllan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.10.144337Hidden diversity: how genetic richness affects species diversity and ecosystem processes in freshwater pondsRecommended by Frederik De Laender based on reviews by Andrew Barnes and Jes HinesBiodiversity loss can have important consequences for ecosystem functions, as exemplified by a large body of literature spanning at least three decades [1–3]. While connections between species diversity and ecosystem functions are now well-defined and understood, the importance of diversity within species is more elusive. Despite a surge in theoretical work on how intraspecific diversity can affect coexistence in simple community types [4,5], not much is known about how intraspecific diversity drives ecosystem processes in more complex community types. One particular challenge is that intraspecific diversity can be expressed as observable variation of functional traits, or instead subsist as genetic variation of which the consequences for ecosystem processes are harder to grasp. References [1] Tilman D, Downing JA (1994) Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature, 367, 363–365. https://doi.org/10.1038/367363a0 | Intraspecific diversity loss in a predator species alters prey community structure and ecosystem functions | Allan Raffard, Julien Cucherousset, José M. Montoya, Murielle Richard, Samson Acoca-Pidolle, Camille Poésy, Alexandre Garreau, Frédéric Santoul & Simon Blanchet. | <p>Loss in intraspecific diversity can alter ecosystem functions, but the underlying mechanisms are still elusive, and intraspecific biodiversity-ecosystem function relationships (iBEF) have been restrained to primary producers. Here, we manipulat... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Freshwater ecology | Frederik De Laender | Andrew Barnes | 2020-06-15 09:04:53 | View |

13 Jul 2020

Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.htmlWhy are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammalsRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Bonaventura Majolo and 1 anonymous reviewer

In social species conflicts among group members typically lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies with dominant individuals outcompeting other groups members and, in some extreme cases, suppressing reproduction of subordinates. It has therefore been typically assumed that dominant individuals have a higher breeding success than subordinates. However, previous work on mammals (mostly primates) revealed high variation, with some populations showing no evidence for a link between female dominance reproductive success, and a meta-analysis on primates suggests that the strength of this relationship is stronger for species with a longer lifespan [1]. Therefore, there is now a need to understand 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals (and beyond) and 2) which factors explains the variation in the strength (and possibly direction) of this relationship. References [1] Majolo, B., Lehmann, J., de Bortoli Vizioli, A., & Schino, G. (2012). Fitness‐related benefits of dominance in primates. American journal of physical anthropology, 147(4), 652-660. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22031 | Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses, Preregistrations, Social structure, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | Bonaventura Majolo, Anonymous | 2020-04-06 17:42:37 | View |

02 Aug 2022

The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammalsShivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8naWhen do dominant females have higher breeding success than subordinates? A meta-analysis across social mammals.Recommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In this meta-analysis, Shivani et al. [1] investigate 1) whether dominance and reproductive success are generally associated across social mammals and 2) whether this relationship varies according to a) life history traits (e.g., stronger for species with large litter size), b) ecological conditions (e.g., stronger when resources are limited) and c) the social environment (e.g., stronger for cooperative breeders than for plural breeders). Generally, the results are consistent with their predictions, except there was no clear support for this relationship to be conditional on the ecological conditions. considered As I have previously recommended the preregistration of this study [2,3], I do not have much to add here, as such recommendation should not depend on the outcome of the study. What I would like to recommend is the whole scientific process performed by the authors, from preregistration sent for peer review, to preprint submission and post-study peer review. It is particularly recommendable to notice that this project was a Masters student project, which shows that it is possible and worthy to preregister studies, even for such rather short-term projects. I strongly congratulate the authors for choosing this process even for an early career short-term project. I think it should be made possible for short-term students to conduct a preregistration study as a research project, without having to present post-study results. I hope this study can encourage a shift in the way we sometimes evaluate students’ projects. I also recommend the readers to look into the whole pre- and post- study reviewing history of this manuscript and the associated preregistration, as it provides a better understanding of the process and a good example of the associated challenges and benefits [4]. It was a really enriching experience and I encourage others to submit and review preregistrations and registered reports!

References [1] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2022). The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals. EcoEvoRxiv, rc8na, ver. 10 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/rc8na [2] Shivani, Huchard, E., Lukas, D. (2020). Preregistration - The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version 1.2 on 07 July 2020. https://dieterlukas.github.io/Preregistration_MetaAnalysis_RankSuccess.html [3] Paquet, M. (2020) Why are dominant females not always showing higher reproductive success? A preregistration of a meta-analysis on social mammals. Peer Community in Ecology, 100056. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100056 [4] Parker, T., Fraser, H., & Nakagawa, S. (2019). Making conservation science more reliable with preregistration and registered reports. Conservation Biology, 33(4), 747-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13342 | The effect of dominance rank on female reproductive success in social mammals | Shivani, Elise Huchard, Dieter Lukas | <p>Life in social groups, while potentially providing social benefits, inevitably leads to conflict among group members. In many social mammals, such conflicts lead to the formation of dominance hierarchies, where high-ranking individuals consiste... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Meta-analyses | Matthieu Paquet | 2021-10-13 18:26:42 | View | |

28 Aug 2023

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30JBehavioral changes in the rapid geographic expansion of the great-tailed grackleRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer

While many species' populations are declining, primarily due to human-related impacts (McKnee et al., 2014), certain species have thrived by utilizing human-influenced environments, leading to their population expansion (Muñoz & Real, 2006). In this context, the capacity to adapt and modify behaviors in response to new surroundings is believed to play a crucial role in facilitating species' spread to novel areas (Duckworth & Badyaev, 2007). For example, an increase in innovative behaviors within recently established communities could aid in discovering previously untapped food resources, while a decrease in exploration might reduce the likelihood of encountering dangers in unfamiliar territories (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016). To investigate the contribution of these behaviors to rapid range expansions, it is essential to directly measure and compare behaviors in various populations of the species. The study conducted by Logan et al. (2023) aims to comprehend the role of behavioral changes in the range expansion of great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). To achieve this, the researchers compared the prevalence of specific behaviors at both the expansion's edge and its middle. Great-tailed grackles were chosen as an excellent model due to their behavioral adaptability, rapid geographic expansion, and their association with human-modified environments. The authors carried out a series of experiments in captivity using wild-caught individuals, following a detailed protocol. The study successfully identified differences in two of the studied behavioral traits: persistence (individuals participated in a larger proportion of trials) and flexibility variance (a component of the species' behavioral flexibility, indicating a higher chance that at least some individuals in the population could be more flexible). Notably, individuals at the edge of the population exhibited higher values of persistence and flexibility, suggesting that these behavioral traits might be contributing factors to the species' expansion. Overall, the study by Logan et al. (2023) is an excellent example of the importance of behavioral flexibility and other related behaviors in the process of species' range expansion and the significance of studying these behaviors across different populations to gain a better understanding of their role in the expansion process. Finally, it is important to underline that this study is part of a pre-registration that received an In Principle Recommendation in PCI Ecology (Sebastián-González 2020) where objectives, methodology, and expected results were described in detail. The authors have identified any deviation from the original pre-registration and thoroughly explained the reasons for their deviations, which were very clear. References Duckworth, R. A., & Badyaev, A. V. (2007). Coupling of dispersal and aggression facilitates the rapid range expansion of a passerine bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(38), 15017-15022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706174104 Griffin, A.S., Guez, D., Federspiel, I., Diquelou, M., Lermite, F. (2016). Invading new environments: A mechanistic framework linking motor diversity and cognition to establishment success. Biological Invasions and Animal Behaviour, 26e46. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139939492.004 Logan, C. J., McCune, K., LeGrande-Rolls, C., Marfori, Z., Hubbard, J., Lukas, D. 2023. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30J McKee, J. K., Sciulli, P. W., Fooce, C. D., & Waite, T. A. (2004). Forecasting global biodiversity threats associated with human population growth. Biological Conservation, 115(1), 161-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00099-5 Muñoz, A. R., & Real, R. (2006). Assessing the potential range expansion of the exotic monk parakeet in Spain. Diversity and Distributions, 12(6), 656-665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2006.00272.x Sebastián González, E. (2020) The role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansion. Peer Community in Ecology, 100062. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100062. Reviewers: Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of species to rapidly expand their geographic range. Great-tailed grackles (<em>Quiscalus mexi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | 2023-04-12 11:00:42 | View | ||

06 Oct 2020

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.htmlThe role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansionRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the relative importance of species-specific traits and environmental factors in modulating species distributions is an intriguing question in ecology [1]. Both behavioral flexibility (i.e., the ability to change the behavior in changing circumstances) and habitat availability are known to influence the ability of a species to expand its geographic range [2,3]. However, the role of each factor is context and species dependent and more information is needed to understand how these two factors interact. In this pre-registration, Logan et al. [4] explain how they will use Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), a species with a flexible behavior and a rapid geographic range expansion, to evaluate the relative role of habitat and behavior as drivers of the species’ expansion [4]. The authors present very clear hypotheses, predicted results and also include alternative predictions. The rationales for all the hypotheses are clearly stated, and the methodology (data and analyses plans) are described with detail. The large amount of information already collected by the authors for the studied species during previous projects warrants the success of this study. It is also remarkable that the authors will make all their data available in a public repository, and that the pre-registration in already stored in GitHub, supporting open access and reproducible science. I agree with the three reviewers of this pre-registration about its value and I think its quality has largely improved during the review process. Thus, I am happy to recommend it and I am looking forward to seeing the results. References [1] Gaston KJ. 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. [2] Sol D, Lefebvre L. 2000. Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to new zealand. Oikos. 90(3): 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.900317.x [3] Hanski I, Gilpin M. 1991. Metapopulation dynamics: Brief history and conceptual domain. Biological journal of the Linnean Society. 42(1-2): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00548.x [4] Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D. 2020. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes (http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html) In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version on 16 Dec 2021 https://github.com/corinalogan/grackles/blob/0fb956040a34986902a384a1d8355de65010effd/Files/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.Rmd. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of a species to rapidly expand their geographic range (e.g., Lefebvre et al. (1997), Griffin a... | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Habitat selection, Human impact, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | Anonymous, Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Tim Parker | 2020-05-14 11:18:57 | View | |

16 Jun 2020

Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback frameworkTim Coulson https://doi.org/10.1101/509067Stasis and the phenotypic gambitRecommended by Tom Van Dooren based on reviews by Jacob Johansson, Katja Räsänen and 1 anonymous reviewerThe preprint "Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework" by Coulson (2020) presents a general framework for evolutionary ecology, useful to interpret patterns of selection and evolutionary responses to environmental transitions. The paper is written in an accessible and intuitive manner. It reviews important concepts which are at the heart of evolutionary ecology. Together, they serve as a worldview which you can carry with you to interpret patterns in data or observations in nature. I very much appreciate it that Coulson (2020) presents his personal intuition laid bare, the framework he uses for his research and how several strong concepts from theoretical ecology fit in there. Overviews as presented in this paper are important to understand how we as researchers put the pieces together. References [1] Coulson, T. (2020) Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework. bioRxiv, 509067, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/509067 | Environmental perturbations and transitions between ecological and evolutionary equilibria: an eco-evolutionary feedback framework | Tim Coulson | <p>I provide a general framework for linking ecology and evolution. I start from the fact that individuals require energy, trace molecules, water, and mates to survive and reproduce, and that phenotypic resource accrual traits determine an individ... |  | Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology | Tom Van Dooren | 2019-01-03 10:05:16 | View | |

07 Oct 2019

Deer slow down litter decomposition by reducing litter quality in a temperate forestSimon Chollet, Morgane Maillard, Juliane Schorghuber, Sue Grayston, Jean-Louis Martin https://doi.org/10.1101/690032Disentangling effects of large herbivores on litter decompositionRecommended by Sébastien Barot based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersAboveground – belowground interactions is a fascinating field that has developed in ecology since about 20 years [1]. This field has been very fruitful as measured by the numerous articles published but also by the particular role it has played in the development of soil ecology. While soil ecology has for a long time developed partially independently from “general ecology” [2], the field of aboveground – belowground interactions has shown that all ecological interactions occurring within the soil are likely to impact plant growth and plant physiology because they have their roots within the soil. In turns, this should impact the aerial system of plants (higher or lower biomasses, changes in leaf quality…), which should cascade on the aboveground food web. Conversely, all ecological interactions occurring aboveground likely impact plant growth, which should cascade to their root systems, and thus to the soil functioning and the soil food web (through changes in the emission of exudates or inputs of dead roots…). Basically, plants are linking the belowground and aboveground worlds because, as terrestrial primary producers, they need to have (1) leaves to capture CO2 and exploit light and (2) roots to absorb water and mineral nutrients. The article I presently recommend [3] tackles this general issue through the prism of the impact of large herbivores on the decomposition of leaf litter. References [1] Hooper, D. U., Bignell, D. E., Brown, V. K., Brussard, L., Dangerfield, J. M., Wall, D. H. and Wolters, V. (2000). Interactions between Aboveground and Belowground Biodiversity in Terrestrial Ecosystems: Patterns, Mechanisms, and Feedbacks. BioScience, 50(12), 1049-1061. doi: 10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[1049:ibaabb]2.0.co;2 | Deer slow down litter decomposition by reducing litter quality in a temperate forest | Simon Chollet, Morgane Maillard, Juliane Schorghuber, Sue Grayston, Jean-Louis Martin | <p>In temperate forest ecosystems, the role of deer in litter decomposition, a key nutrient cycling process, remains debated. Deer may modify the decomposition process by affecting plant cover and thus modifying litter abundance. They can also alt... | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory, Soil ecology | Sébastien Barot | 2019-07-04 14:30:19 | View | ||

12 Oct 2020

Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predationAlex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042317Tree diversity is associated with reduced herbivory in urban forestRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Ian Pearse based on reviews by Ian Pearse and Freerk MollemanUrban ecology, the study of ecological systems in our increasingly urbanized world, is crucial to planning and redesigning cities to enhance ecosystem services (Kremer et al. 2016), human health and well-being and further conservation goals (Dallimer et al. 2012). Urban trees are a crucial component of urban streets and parks that provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration (Fung and Jim 2019), improve air quality (Lai and Kontokosta 2019), help control storm water (Johnson and Handel 2016), and conserve wildlife (Herrmann et al. 2012; de Andrade et al. 2020). References Airola, D. and Greco, S. (2019). Birds and oaks in California’s urban forest. Int. Oaks, 30, 109–116. | Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predation | Alex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol | <p>Insect herbivory is an important component of forest ecosystems functioning and can affect tree growth and survival. Tree diversity is known to influence insect herbivory in natural forest, with most studies reporting a decrease in herbivory wi... |  | Biodiversity, Biological control, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | 2020-04-20 13:49:36 | View | |

13 Mar 2021

Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersalSevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6behDispersal: from “neutral” to a state- and context-dependent viewRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersTraditionally, dispersal has often been seen as “random” or “neutral” as Lowe & McPeek (2014) have put it. This simplistic view is likely due to dispersal being intrinsically difficult to measure empirically as well as “random” dispersal being a convenient simplifying assumption in theoretical work. Clobert et al. (2009), and many others, have highlighted how misleading this assumption is. Rather, dispersal seems to be usually a complex reaction norm, depending both on internal as well as external factors. One such internal factor is the sex of the dispersing individual. A recent review of the theoretical literature (Li & Kokko 2019) shows that while ideas explaining sex-biased dispersal go back over 40 years this state-dependency of dispersal is far from comprehensively understood. Sevchik et al. (2021) tackle this challenge empirically in a bird species, the great-tailed grackle. In contrast to most bird species, where females disperse more than males, the authors report genetic evidence indicating male-biased dispersal. The authors argue that this difference can be explained by the great-tailed grackle’s social and mating-system. Dispersal is a central life-history trait (Bonte & Dahirel 2017) with major consequences for ecological and evolutionary processes and patterns. Therefore, studies like Sevchik et al. (2021) are valuable contributions for advancing our understanding of spatial ecology and evolution. Importantly, Sevchik et al. also lead to way to a more open and reproducible science of ecology and evolution. The authors are among the pioneers of preregistering research in their field and their way of doing research should serve as a model for others. References Bonte, D. & Dahirel, M. (2017) Dispersal: a central and independent trait in life history. Oikos 126: 472-479. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.03801 Clobert, J., Le Galliard, J. F., Cote, J., Meylan, S. & Massot, M. (2009) Informed dispersal, heterogeneity in animal dispersal syndromes and the dynamics of spatially structured populations. Ecol. Lett.: 12, 197-209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01267.x Li, X.-Y. & Kokko, H. (2019) Sex-biased dispersal: a review of the theory. Biol. Rev. 94: 721-736. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12475 Lowe, W. H. & McPeek, M. A. (2014) Is dispersal neutral? Trends Ecol. Evol. 29: 444-450. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.05.009 Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. & Lukas, D. (2021) Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal. EcoEvoRxiv, osf.io/t6beh, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/t6beh | Investigating sex differences in genetic relatedness in great-tailed grackles in Tempe, Arizona to infer potential sex biases in dispersal | Sevchik, A., Logan, C. J., McCune, K. B., Blackwell, A., Rowney, C. and Lukas, D | <p>In most bird species, females disperse prior to their first breeding attempt, while males remain closer to the place they hatched for their entire lives. Explanations for such female bias in natal dispersal have focused on the resource-defense ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Dispersal & Migration, Zoology | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-08-24 17:53:06 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle