Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * ▲ | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

01 Apr 2019

The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patternsJean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman https://doi.org/10.1101/431296Diversity-Stability and the Structure of PerturbationsRecommended by Kevin Cazelles and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frederic Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewer

In his 1972 paper “Will a Large Complex System Be Stable?” [1], May challenges the idea that large communities are more stable than small ones. This was the beginning of a fundamental debate that still structures an entire research area in ecology: the diversity-stability debate [2]. The most salient strength of May’s work was to use a mathematical argument to refute an idea based on the observations that simple communities are less stable than large ones. Using the formalism of dynamical systems and a major results on the distribution of the eigen values for random matrices, May demonstrated that the addition of random interactions destabilizes ecological communities and thus, rich communities with a higher number of interactions should be less stable. But May also noted that his mathematical argument holds true only if ecological interactions are randomly distributed and thus concluded that this must not be true! This is how the contradiction between mathematics and empirical observations led to new developments in the study of ecological networks. References [1] May, Robert M (1972). Will a Large Complex System Be Stable? Nature 238, 413–414. doi: 10.1038/238413a0 | The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patterns | Jean-François Arnoldi, Michel Loreau, Bart Haegeman | <p>Empirical knowledge of ecosystem stability and diversity-stability relationships is mostly based on the analysis of temporal variability of population and ecosystem properties. Variability, however, often depends on external factors that act as... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Kevin Cazelles | 2018-10-02 14:01:03 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

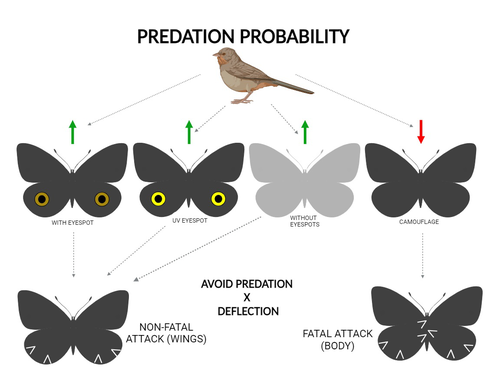

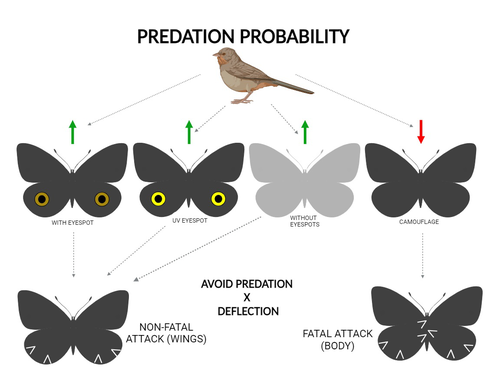

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

23 Oct 2023

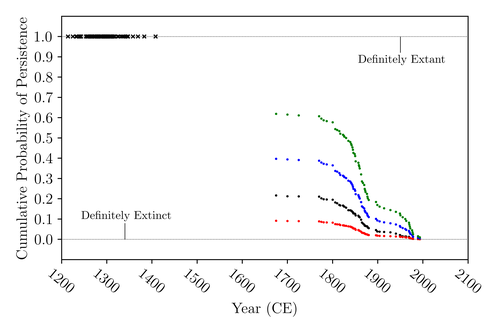

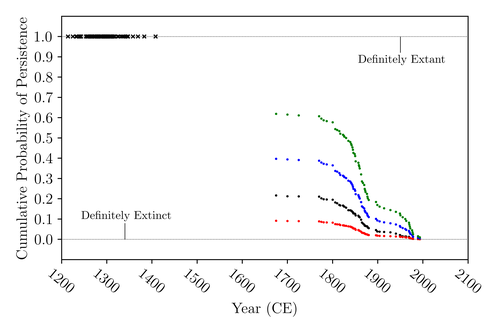

The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went ExtinctFloe Foxon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261Are Moas ancient Lazarus species?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway based on reviews by Tim Coulson and Richard Holdaway

Ancient human colonisation often had catastrophic consequences for native fauna. The North American Megafauna went extinct shortly after humans entered the scene and Madagascar suffered twice, before 1500 CE and around 1700 CE after the Malayan and European colonisation. Maoris colonised New Zealand by about 1300 and a century later the giant Moa birds (Dinornithiformes) sharply declined. But did they went extinct or are they an ancient example of Lazarus species, species thought to be extinct but still alive? Scattered anecdotes of late sightings of living Moas even up to the 20th century seem to suggest the latter. The quest for later survival has also a criminal aspect. Who did it, the Maoris or the white colonisers in the late 18th century? The present work by Floe Foxon (2023) tries to settle this question. It uses a survival modelling approach and an assessment of the reliability of nearly 100 alleged sightings. The model favours the so-called overkill hypothesis, that Moas probably went extinct in the 15th century shortly after Maori colonisation. A small but still remarkable probability remained for survival up to 1770. Later sightings turned out to be highly unreliable. The paper is important as it does not rely on subjective discussions of late sightings but on a probabilistic modelling approach with sensitivity testing prior applied to marsupials. As common in probabilistic approaches, the study does not finally settle the case. A probability of as much as 20% remained for late survival after 1450 CE. This is not improbable as New Zealand was sufficiently unexplored in those days to harbour a few refuges for late survivors. However, in this respect, it is a bit unfortunate that at the end of the discussion, the paper cites Heuvelmans, the founder of cryptozoology, and it mentions the ivory-billed woodpecker, which has recently been redetected. No Moa remains were found after 1450. References Foxon F (2023) The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct. bioRxiv, 2023.08.07.552261, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.07.552261 | The Moa the Merrier: Resolving When the Dinornithiformes Went Extinct | Floe Foxon | <p style="text-align: justify;">The Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are an extinct group of the ratite clade from New Zealand. The overkill hypothesis asserts that the first New Zealand settlers hunted the Moa to extinction by 1450 CE, whereas the st... |  | Conservation biology, Human impact, Statistical ecology, Zoology | Werner Ulrich | Tim Coulson, Richard Holdaway | 2023-08-08 17:14:30 | View |

06 Mar 2020

The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategiesCharlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux https://doi.org/10.1101/790634The importance of spatio-temporal dynamics on MPA's designRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Ana S. L. Rodrigues and 1 anonymous reviewerMarine protected areas (MPA) have arisen as the main approach for conservation of marine species. Fishes, marine mammals and birds can be conservation targets that justify the implementation of these areas. However, MPAs undergo many of the problems faced by their terrestrial equivalent. One of the major concerns is that these conservation areas are spatially constrained, by logistic reasons, and many times these constraints caused that key areas for the species (reproductive sites, refugees, migration) fall outside the limits, making conservation efforts even more difficult. Lambert et al. [1] evaluate at what point the Bay of Biscay MPA contains key ecological areas for several emblematic species. The evaluation incorporated a spatio-temporal dimension. To evaluate these ideas, authors evaluate two population descriptors: aggregation and persistence of several species of cetaceans and seabirds. References [1] Lambert, C., Dorémus, G. and V. Ridoux (2020) The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies. bioRxiv, 790634, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/790634 | The persistence in time of distributional patterns in marine megafauna impacts zonal conservation strategies | Charlotte Lambert, Ghislain Dorémus, Vincent Ridoux | <p>The main type of zonal conservation approaches corresponds to Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), which are spatially defined and generally static entities aiming at the protection of some target populations by the implementation of a management pla... |  | Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Species distributions | Sergio Estay | 2019-10-03 08:47:17 | View | |

29 Dec 2018

The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food webInmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat https://doi.org/10.1101/324178From deserts to avocado orchards - understanding realized trophic interactions in communitiesRecommended by Francis John Burdon based on reviews by Owen Petchey and 2 anonymous reviewersThe late eminent ecologist Gary Polis once stated that “most catalogued food-webs are oversimplified caricatures of actual communities” and are “grossly incomplete representations of communities in terms of both diversity and trophic connections.” Not content with that damning indictment, he went further by railing that “theorists are trying to explain phenomena that do not exist” [1]. The latter critique might have been push back for Robert May´s ground-breaking but ultimately flawed research on the relationship between food-web complexity and stability [2]. Polis was a brilliant ecologist, and his thinking was clearly influenced by his experiences researching desert food webs. Those food webs possess an uncommon combination of properties, such as frequent omnivory, cannibalism, and looping; high linkage density (L/S); and a nearly complete absence of apex consumers, since few species completely lack predators or parasites [3]. During my PhD studies, I was lucky enough to visit Joshua Tree National Park on the way to a conference in New England, and I could immediately see the problems posed by desert ecosystems. At the time, I was ruminating on the “harsh-benign” hypothesis [4], which predicts that the relative importance of abiotic and biotic forces should vary with changes in local environmental conditions (from harsh to benign). Specifically, in more “harsh” environments, abiotic factors should determine community composition whilst weakening the influence of biotic interactions. However, in the harsh desert environment I saw first-hand evidence that species interactions were not diminished; if anything, they were strengthened. Teddy-bear chollas possessed murderously sharp defenses to protect precious water, creosote bushes engaged in belowground “chemical warfare” (allelopathy) to deter potential competitors, and rampant cannibalism amongst scorpions drove temporal and spatial ontogenetic niche partitioning. Life in the desert was hard, but you couldn´t expect your competition to go easy on you. References [1] Polis, G. A. (1991). Complex trophic interactions in deserts: an empirical critique of food-web theory. The American Naturalist, 138(1), 123-155. doi: 10.1086/285208 | The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web | Inmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat | <p>The mathematical theory describing small assemblages of interacting species (community modules or motifs) has proved to be essential in understanding the emergent properties of ecological communities. These models use differential equations to ... |  | Community ecology, Experimental ecology | Francis John Burdon | 2018-05-16 19:34:10 | View | |

03 Feb 2023

The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pairJeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879peDrivers of range expansion in a pair of sister grackle speciesRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The spatial distribution of a species is driven by both biotic and abiotic factors that may change over time (Soberón & Nakamura, 2009; Paquette & Hargreaves, 2021). Therefore, species ranges are dynamic, especially in humanized landscapes where changes occur at high speeds (Sirén & Morelli, 2020). The distribution of many species is being reduced because of human impacts; however, some species are expanding their distributions, even over their niche (Lustenhouwer & Parker, 2022). One of the factors that may lead to a geographic niche expansion is behavioral flexibility (Mikhalevich et al., 2017), but the mechanisms determining range expansion through behavioral changes are not fully understood. The PCI Ecology study by Summers et al. (2023) uses a very large database on the current and historic distribution of two species of grackles that have shown different trends in their distribution. The great-tailed grackle has largely expanded its range over the 20th century, while the range of the boat-tailed grackle has remained very similar. They take advantage of this differential response in the distribution of the two species and run several analyses to test whether it was a change in habitat availability, in the realized niche, in habitat connectivity or in in the other traits or conditions that previously limited the species range, what is driving the observed distribution of the species. The study finds a change in the niche of great-tailed grackle, consistent with the high behavioral flexibility of the species. The two reviewers and I have seen a lot of value in this study because 1) it addresses a very timely question, especially in the current changing world; 2) it is a first step to better understanding if behavioral attributes may affect species’ ability to change their niche; 3) it contrasts the results using several complementary statistical analyses, reinforcing their conclusions; 4) it is based on the preregistration Logan et al (2021), and any deviations from it are carefully explained and justified in the text and 5) the limitations of the study have been carefully discussed. It remains to know if the boat-tailed grackle has more limited behavioral flexibility than the great-tailed grackle, further confirming the results of this study. Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D (2021) Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html Lustenhouwer N, Parker IM (2022) Beyond tracking climate: Niche shifts during native range expansion and their implications for novel invasions. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14395 Mikhalevich I, Powell R, Logan C (2017) Is behavioural flexibility evidence of cognitive complexity? How evolution can inform comparative cognition. Interface Focus, 7, 20160121. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121 Paquette A, Hargreaves AL (2021) Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters, 24, 2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864 Sirén APK, Morelli TL (2020) Interactive range-limit theory (iRLT): An extension for predicting range shifts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89, 940–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13150 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Summers JT, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2022) The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe | The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair | Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen | <p>---This is a POST-STUDY manuscript for the PREREGISTRATION, which received in principle acceptance in 2020 from Dr. Sebastián González (reviewed by Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow; <a href="https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ec... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biogeography, Dispersal & Migration, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Preregistrations, Species distributions | Esther Sebastián González | 2022-05-26 20:07:33 | View | |

25 Oct 2021

The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakesNicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner https://doi.org/10.1101/373332The difficult interpretation of species co-distributionRecommended by Dominique Gravel based on reviews by Anthony Maire and Emilie MackeEcology is the study of the distribution of organisms in space and time and their interactions. As such, there is a tradition of studies relating abiotic environmental conditions to species distribution, while another one is concerned by the effects of consumers on the abundance of their resources. Interestingly, joining the dots appears more difficult than it would suggest: eluding the effect of species interactions on distribution remains one of the greatest challenges to elucidate nowadays (Kissling et al. 2012). Theory suggests that yes, species interactions such as predation and competition should influence range limits (Godsoe et al. 2017), but the common intuition among many biogeographers remains that over large areas such as regions and continents, environmental drivers like temperature and precipitation overwhelm their local effects. Answering this question is of primary importance in the context where species are moving around with climate warming. Inconsistencies in food web structure may arise with asynchronized movements of consumers and their resources, leading to a major disruption in regulation and potentially ecosystem functioning. Solving this problem, however, remains very challenging because we have to rely on observational data since experiments are hard to perform at the biogeographical scale. The study of St-Gelais is an interesting step forward to solve this problem. Their main objective was to assess the strength of the association between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities at a large spatial scale, looking at the spatial covariation of both taxonomic and functional composition. To do so, they undertook a massive survey of more than 100 lakes across three regions of the boreal region of Québec. Species and functional composition were recorded, along with a set of abiotic variables. Classic community ecology at this point. The difficulty they faced was to disentangle the multiple causal relationships involved in the distribution of both trophic levels. Teasing apart bottom-up and top-down forces driving the assembly of plankton communities using observational data is not an easy task. On the one hand, both trophic levels could respond to variations in temperature, nutrient availability and dissolved organic carbon. The interpretation is fairly straightforward if the two levels respond to different factors, but the situation is much more complicated when they do respond similarly. There are potentially three possible underlying scenarios. First, the phyto and zooplankton communities may share the same environmental requirements, thereby generating a joint distribution over gradients such as temperature and nutrient availability. Second, the abiotic environment could drive the distribution of the phytoplankton community, which would then propagate up and influence the distribution of the zooplankton community. Alternatively, the abiotic environment could constrain the distribution of the zooplankton, which could then affect the one of phytoplankton. In addition to all of these factors, St-Gelais et al also consider that dispersal may limit the distribution, well aware of previous studies documenting stronger dispersal limitations for zooplankton communities. Unfortunately, there is not a single statistical approach that could be taken from the shelf and used to elucidate drivers of co-distribution. Joint species distribution was once envisioned as a major step forward in this direction (Warton et al. 2015), but there are several limits preventing the direct interpretation that co-occurrence is linked to interactions (Blanchet et al. 2020). Rather, St-Gelais used a variety of multivariate statistics to reveal the structure in their observational data. First, using a Procrustes analysis (a method testing if the spatial variation of one community is correlated to the structure of another community), they found a significant correlation between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities, indicating a taxonomic coupling between the groups. Interestingly, this observation was maintained for functional composition only when interaction-related traits were considered. At this point, these results strongly suggest that interactions are involved in the correlation, but it's hard to decipher between bottom-up and top-down perspectives. A complementary analysis performed with a constrained ordination, per trophic level, provided complementary pieces of information. First observation was that only functional variation was found to be related to the different environmental variables, not taxonomic variation. Despite that trophic levels responded to water quality variables, spatial autocorrelation was more important for zooplankton communities and the two layers appear to respond to different variables. It is impossible with those results to formulate a strong conclusion about whether grazing influence the co-distribution of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities. That's the mere nature of observational data. While there is a strong spatial association between them, there are also diverging responses to the different environmental variables considered. But the contrast between taxonomic and functional composition is nonetheless informative and it seems that beyond the idiosyncrasies of species composition, trait distribution may be more informative and general. Perhaps the most original contribution of this study is the hierarchical approach to analyze the data, combined with the simultaneous analysis of taxonomic and functional distributions. Having access to a vast catalog of multivariate statistical techniques, a careful selection of analyses helps revealing key features in the data, rejecting some hypotheses and accepting others. Hopefully, we will see more and more of such multi-trophic approaches to distribution because it is now clear that the factors driving distribution are much more complicated than anticipated in more traditional analyses of community data. Biodiversity is more than a species list, it is also all of the interactions between them, influencing their distribution and abundance (Jordano 2016). References Blanchet FG, Cazelles K, Gravel D (2020) Co-occurrence is not evidence of ecological interactions. Ecology Letters, 23, 1050–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13525 Godsoe W, Jankowski J, Holt RD, Gravel D (2017) Integrating Biogeography with Contemporary Niche Theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.03.008 Jordano P (2016) Chasing Ecological Interactions. PLOS Biology, 14, e1002559. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002559 Kissling WD, Dormann CF, Groeneveld J, Hickler T, Kühn I, McInerny GJ, Montoya JM, Römermann C, Schiffers K, Schurr FM, Singer A, Svenning J-C, Zimmermann NE, O’Hara RB (2012) Towards novel approaches to modelling biotic interactions in multispecies assemblages at large spatial extents. Journal of Biogeography, 39, 2163–2178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02663.x St-Gelais NF, Vogt RJ, Giorgio PA del, Beisner BE (2021) The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes. bioRxiv, 373332, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/373332 Warton DI, Blanchet FG, O’Hara RB, Ovaskainen O, Taskinen S, Walker SC, Hui FKC (2015) So Many Variables: Joint Modeling in Community Ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30, 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.007 Wisz MS, Pottier J, Kissling WD, Pellissier L, Lenoir J, Damgaard CF, Dormann CF, Forchhammer MC, Grytnes J-A, Guisan A, Heikkinen RK, Høye TT, Kühn I, Luoto M, Maiorano L, Nilsson M-C, Normand S, Öckinger E, Schmidt NM, Termansen M, Timmermann A, Wardle DA, Aastrup P, Svenning J-C (2013) The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews, 88, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x | The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes | Nicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner | <p>Strong trophic interactions link primary producers (phytoplankton) and consumers (zooplankton) in lakes. However, the influence of such interactions on the biogeographical distribution of the taxa and functional traits of planktonic organ... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Species distributions | Dominique Gravel | 2018-07-24 15:01:51 | View | |

19 Aug 2020

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metricsF. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux https://doi.org/10.1101/640995Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systemsRecommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersConservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4]. References [1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton. | Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View | |

08 Aug 2020

Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predatorChris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips https://doi.org/10.1101/856997While the quoll’s away, the mice will play… and the seeds will payRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA predator can strongly influence the demography of its prey, which can have profound carryover effects on the trophic network; so-called density-mediated indirect interactions (DMII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006). Furthermore, a novel predator can alter the phenotypes of its prey for traits that will change prey foraging efficiency. These trait-mediated indirect interactions may in turn have cascading effects on the demography and features of the basal resources consumed by the intermediate consumer (TMIII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006), but very few studies have looked for these effects (Trusell et al. 2006). The study “Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator”, by Jolly et al. (2020) is therefore a much-needed addition to knowledge in this field. The authors have profited from a rare introduction of Northern quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus) on an Australian island, to examine both the density-mediated and trait-mediated indirect interactions with grassland melomys (Melomys burtoni) and the vegetation of their woodland habitat. References -Bell G, Gonzalez A (2009) Evolutionary rescue can prevent extinction following environmental change. Ecology letters, 12(9), 942-948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01350.x | Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator | Chris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips | <p>The arrival of novel predators can trigger trophic cascades driven by shifts in prey numbers. Predators also elicit behavioural change in prey populations, via phenotypic plasticity and/or rapid evolution, and such changes may also contribute t... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Foraging, Herbivory, Population ecology, Terrestrial ecology, Tropical ecology | Denis Réale | 2019-11-27 21:39:44 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle