Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

21 Dec 2020

Influence of local landscape and time of year on bat-road collision risksCharlotte Roemer, Aurélie Coulon, Thierry Disca, and Yves Bas https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.15.204115Assessing bat-vehicle collision risks using acoustic 3D trackingRecommended by Gloriana Chaverri based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ? based on reviews by Mark Brigham and ?

The loss of biodiversity is an issue of great concern, especially if the extinction of species or the loss of a large number of individuals within populations results in a loss of critical ecosystem services. We know that the most important threat to most species is habitat loss and degradation (Keil et al., 2015; Pimm et al., 2014); the latter can be caused by multiple anthropogenic activities, including pollution, introduction of invasive species and fragmentation (Brook et al., 2008; Scanes, 2018). Roads are a major cause of habitat fragmentation, isolating previously connected populations and being a direct source of mortality for animals that attempt to cross them (Spellberg, 1998). References [1] Bartonička T, Andrášik R, Duľa M, Sedoník J, Bíl M (2018) Identification of local factors causing clustering of animal-vehicle collisions. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 82, 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.21467 | Influence of local landscape and time of year on bat-road collision risks | Charlotte Roemer, Aurélie Coulon, Thierry Disca, and Yves Bas | <p>Roads impact bat populations through habitat loss and collisions. High quality habitats particularly increase bat mortalities on roads, yet many questions remain concerning how local landscape features may influence bat behaviour and lead to hi... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Human impact, Landscape ecology | Gloriana Chaverri | 2020-07-20 10:56:29 | View | |

03 Feb 2023

The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pairJeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879peDrivers of range expansion in a pair of sister grackle speciesRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The spatial distribution of a species is driven by both biotic and abiotic factors that may change over time (Soberón & Nakamura, 2009; Paquette & Hargreaves, 2021). Therefore, species ranges are dynamic, especially in humanized landscapes where changes occur at high speeds (Sirén & Morelli, 2020). The distribution of many species is being reduced because of human impacts; however, some species are expanding their distributions, even over their niche (Lustenhouwer & Parker, 2022). One of the factors that may lead to a geographic niche expansion is behavioral flexibility (Mikhalevich et al., 2017), but the mechanisms determining range expansion through behavioral changes are not fully understood. The PCI Ecology study by Summers et al. (2023) uses a very large database on the current and historic distribution of two species of grackles that have shown different trends in their distribution. The great-tailed grackle has largely expanded its range over the 20th century, while the range of the boat-tailed grackle has remained very similar. They take advantage of this differential response in the distribution of the two species and run several analyses to test whether it was a change in habitat availability, in the realized niche, in habitat connectivity or in in the other traits or conditions that previously limited the species range, what is driving the observed distribution of the species. The study finds a change in the niche of great-tailed grackle, consistent with the high behavioral flexibility of the species. The two reviewers and I have seen a lot of value in this study because 1) it addresses a very timely question, especially in the current changing world; 2) it is a first step to better understanding if behavioral attributes may affect species’ ability to change their niche; 3) it contrasts the results using several complementary statistical analyses, reinforcing their conclusions; 4) it is based on the preregistration Logan et al (2021), and any deviations from it are carefully explained and justified in the text and 5) the limitations of the study have been carefully discussed. It remains to know if the boat-tailed grackle has more limited behavioral flexibility than the great-tailed grackle, further confirming the results of this study. Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D (2021) Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html Lustenhouwer N, Parker IM (2022) Beyond tracking climate: Niche shifts during native range expansion and their implications for novel invasions. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14395 Mikhalevich I, Powell R, Logan C (2017) Is behavioural flexibility evidence of cognitive complexity? How evolution can inform comparative cognition. Interface Focus, 7, 20160121. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121 Paquette A, Hargreaves AL (2021) Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters, 24, 2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864 Sirén APK, Morelli TL (2020) Interactive range-limit theory (iRLT): An extension for predicting range shifts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89, 940–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13150 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Summers JT, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2022) The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe | The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair | Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen | <p>---This is a POST-STUDY manuscript for the PREREGISTRATION, which received in principle acceptance in 2020 from Dr. Sebastián González (reviewed by Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow; <a href="https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ec... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biogeography, Dispersal & Migration, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Preregistrations, Species distributions | Esther Sebastián González | 2022-05-26 20:07:33 | View | |

06 Oct 2020

Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range?Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gspaceuse.htmlExplore and move: a key to success in a changing world?Recommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Joe Nocera, Marion Nicolaus and Laure CauchardChanges in the spatial range of many species are one of the major consequences of the profound alteration of environmental conditions due to human activities. Some species expand, sometimes spectacularly during invasions; others decline; some shift. Because these changes result in local biodiversity loss (whether local species go extinct or are replaced by colonizing ones), understanding the factors driving spatial range dynamics appears crucial to predict biodiversity dynamics. Identifying the factors that shape individual movement is a main step towards such understanding. The study described in this preregistration (McCune et al. 2020) falls within this context by testing possible links between individual exploration behaviour and movements related to daily space use in an avian study model currently rapidly expanding, the great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus). Movement and exploration: which direction(s) for the link between exploration and dispersal? Evolutionary and conservation perspectives References Badayev, A. V., Martin, T. E and Etges, W. J. 1996. Habitat sampling and habitat selection by female wild turkeys: ecological correlates and reproductive consequences. Auk 113: 636-646. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/4088984 | Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range? | Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) are rapidly expanding their geographic range (Wehtje 2003). Range expansion could be facilitated by consistent behavioural differences between individuals on the range edge and those in other parts of th... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Blandine Doligez | 2019-09-30 19:27:40 | View | |

06 Oct 2020

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.htmlThe role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansionRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the relative importance of species-specific traits and environmental factors in modulating species distributions is an intriguing question in ecology [1]. Both behavioral flexibility (i.e., the ability to change the behavior in changing circumstances) and habitat availability are known to influence the ability of a species to expand its geographic range [2,3]. However, the role of each factor is context and species dependent and more information is needed to understand how these two factors interact. In this pre-registration, Logan et al. [4] explain how they will use Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), a species with a flexible behavior and a rapid geographic range expansion, to evaluate the relative role of habitat and behavior as drivers of the species’ expansion [4]. The authors present very clear hypotheses, predicted results and also include alternative predictions. The rationales for all the hypotheses are clearly stated, and the methodology (data and analyses plans) are described with detail. The large amount of information already collected by the authors for the studied species during previous projects warrants the success of this study. It is also remarkable that the authors will make all their data available in a public repository, and that the pre-registration in already stored in GitHub, supporting open access and reproducible science. I agree with the three reviewers of this pre-registration about its value and I think its quality has largely improved during the review process. Thus, I am happy to recommend it and I am looking forward to seeing the results. References [1] Gaston KJ. 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. [2] Sol D, Lefebvre L. 2000. Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to new zealand. Oikos. 90(3): 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.900317.x [3] Hanski I, Gilpin M. 1991. Metapopulation dynamics: Brief history and conceptual domain. Biological journal of the Linnean Society. 42(1-2): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00548.x [4] Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D. 2020. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes (http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html) In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version on 16 Dec 2021 https://github.com/corinalogan/grackles/blob/0fb956040a34986902a384a1d8355de65010effd/Files/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.Rmd. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of a species to rapidly expand their geographic range (e.g., Lefebvre et al. (1997), Griffin a... | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Habitat selection, Human impact, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | Anonymous, Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Tim Parker | 2020-05-14 11:18:57 | View | |

08 Aug 2020

Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predatorChris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips https://doi.org/10.1101/856997While the quoll’s away, the mice will play… and the seeds will payRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA predator can strongly influence the demography of its prey, which can have profound carryover effects on the trophic network; so-called density-mediated indirect interactions (DMII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006). Furthermore, a novel predator can alter the phenotypes of its prey for traits that will change prey foraging efficiency. These trait-mediated indirect interactions may in turn have cascading effects on the demography and features of the basal resources consumed by the intermediate consumer (TMIII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006), but very few studies have looked for these effects (Trusell et al. 2006). The study “Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator”, by Jolly et al. (2020) is therefore a much-needed addition to knowledge in this field. The authors have profited from a rare introduction of Northern quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus) on an Australian island, to examine both the density-mediated and trait-mediated indirect interactions with grassland melomys (Melomys burtoni) and the vegetation of their woodland habitat. References -Bell G, Gonzalez A (2009) Evolutionary rescue can prevent extinction following environmental change. Ecology letters, 12(9), 942-948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01350.x | Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator | Chris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips | <p>The arrival of novel predators can trigger trophic cascades driven by shifts in prey numbers. Predators also elicit behavioural change in prey populations, via phenotypic plasticity and/or rapid evolution, and such changes may also contribute t... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Foraging, Herbivory, Population ecology, Terrestrial ecology, Tropical ecology | Denis Réale | 2019-11-27 21:39:44 | View | |

15 Jun 2020

Investigating the rare behavior of male parental care in great-tailed gracklesFolsom MA, MacPherson M, Lukas D, McCune KB, Bergeron L, Bond A, Blackwell A, Rowney C, Logan CJ https://github.com/corinalogan/grackles/blob/master/Files/Preregistrations/gmalecare.RmdStudying a rare behavior in a polygamous bird: male parental care in great-tailed gracklesRecommended by Marie-Jeanne Holveck based on reviews by Matthieu Paquet and André C FerreiraThe Great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) is a polygamous bird species that is originating from Central America and rapidly expanding its geographic range toward the North, and in which females were long thought to be the sole nest builders and caretakers of the young. In their pre-registration [1], Folsom and collaborators report repeated occurrences of male parental care and develop hypotheses aiming at better understanding the occurrence and the fitness consequences of this very rarely observed male behavior. They propose to assess if male parental care correlates with the circulating levels of several relevant hormones, increases offspring survival, is a local adaptation, and is a mating strategy, in surveying three populations located in Arizona (middle of the geographic range expansion), California (northern edge of the geographic range), and in Central America (core of the range). This study is part of a 5-year bigger project. References [1] Folsom MA, MacPherson M, Lukas D, McCune KB, Bergeron L, Bond A, Blackwell A, Rowney C, Logan CJ. 2020. Investigating the rare behavior of male parental care in great-tailed grackles. corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gmalecare.html In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version on 15 June 2020 corinalogan/grackles/blob/master/Files/Preregistrations/gmalecare.Rmd. | Investigating the rare behavior of male parental care in great-tailed grackles | Folsom MA, MacPherson M, Lukas D, McCune KB, Bergeron L, Bond A, Blackwell A, Rowney C, Logan CJ | This is a PREREGISTRATION submitted for pre-study peer review. Our planned data collection START DATE is May 2020, therefore it would be ideal if the peer review process could be completed before then. Abstract: Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Preregistrations, Zoology | Marie-Jeanne Holveck | 2019-12-05 17:38:47 | View | |

12 Jan 2022

No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria MosquitoesSerge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542The search for sex pheromones in malaria mosquitoesRecommended by Niels Verhulst based on reviews by Marcelo Lorenzo and 1 anonymous reviewerPheromones are used by many insects to find the opposite sex for mating. Especially for nocturnal mosquitoes it seems logical that such pheromones exist as they can only partly rely on visual cues when flying at night. The males of many mosquito species form swarms and conspecific females fly into these swarms to mate. The two sibling species of malaria mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii coexist and both form swarms consisting of only one species. Although hybrids can be produced, these hybrids are rarely found in nature. In the study presented by Poda and colleagues (2022) it was tested if long-range sex pheromones exist in these two mosquito sibling species. In a previous study by Mozūraites et al. (2020), five compounds (acetoin, sulcatone, octanal, nonanal and decanal) were identified that induced male swarming and increase mating success. Interestingly these compounds are frequently found in nature and have been shown to play a role in sugar feeding or host finding of An. gambiae. In the recommended study performed by Poda et al. (2022) no evidence of long-range sex pheromones in A. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii was found. The discrepancy between the two studies is difficult to explain but some of the methods varied between studies. Mozūraites et al. (2020) for example, collected odours from mosquitoes in small 1l glass bottles, where swarming is questionable, while in the study of Poda et al. (2022) 50 x 40 x 40 cm cages were used and swarming observed, although most swarms are normally larger. On the other hand, some of the analytical techniques used in the Mozūraites et al. (2020) study were more sensitive while others were more sensitive in the Poda et al. (2022) study. Because it is difficult to prove that something does not exist, the authors nicely indicate that “an absence of evidence is not an evidence of absence” (Poda et al., 2022). Nevertheless, recently colonized species were tested in large cage setups where swarming was observed and various methods were used to try to detect sex pheromones. No attraction to the volatile blend from male swarms was detected in an olfactometer, no antenna-electrophysiological response of females to male swarm volatile compounds was detected and no specific male swarm volatile was identified. This study will open the discussion again if (sex) pheromones play a role in swarming and mating of malaria mosquitoes. Future studies should focus on sensitive real-time volatile analysis in mating swarms in large cages or field settings. In comparison to moths for example that are very sensitive to very specific pheromones and attract from a large distance, such a long-range specific pheromone does not seem to exist in these mosquito species. Acoustic and visual cues have been shown to be involved in mating (Diabate et al., 2003; Gibson and Russell, 2006) and especially at long distances, visual cues are probably important for the detection of these swarms. References Diabate A, Baldet T, Brengues C, Kengne P, Dabire KR, Simard F, Chandre F, Hougard JM, Hemingway J, Ouedraogo JB, Fontenille D (2003) Natural swarming behaviour of the molecular M form of Anopheles gambiae. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 97, 713–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(03)80110-4 Gibson G, Russell I (2006) Flying in Tune: Sexual Recognition in Mosquitoes. Current Biology, 16, 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.053 Mozūraitis, R., Hajkazemian, M., Zawada, J.W., Szymczak, J., Pålsson, K., Sekar, V., Biryukova, I., Friedländer, M.R., Koekemoer, L.L., Baird, J.K., Borg-Karlson, A.-K., Emami, S.N. (2020) Male swarming aggregation pheromones increase female attraction and mating success among multiple African malaria vector mosquito species. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4, 1395–1401. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1264-9 Poda, S.B., Buatois, B., Lapeyre, B., Dormont, L., Diabate, A., Gnankine, O., Dabire, R.K., Roux, O. (2022) No evidence for long-range male sex pheromones in two malaria mosquitoes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.05.187542, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.05.187542 | No Evidence for Long-range Male Sex Pheromones in Two Malaria Mosquitoes | Serge Bèwadéyir Poda, Bruno Buatois, Benoit Lapeyre, Laurent Dormont, Abdoulaye Diabaté, Olivier Gnankiné, Roch K. Dabiré, Olivier Roux | <p style="text-align: justify;">Cues involved in mate seeking and recognition prevent hybridization and can be involved in speciation processes. In malaria mosquitoes, females of the two sibling species <em>Anopheles gambiae</em> s.s. and <em>An. ... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Chemical ecology | Niels Verhulst | 2021-04-26 12:28:36 | View | |

28 Feb 2023

Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird communityAmbre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715Two common European songbirds elicit different community responses with their mobbing callsRecommended by Tim Parker based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Many bird species participate in mobbing in which individuals approach a predator while producing conspicuous vocalizations (Magrath et al. 2014). Mobbing is interesting to behavioral ecologists because of the complex array of costs of benefits. Costs range from the obvious risk of approaching a predator while drawing that predator’s attention to the more mundane opportunity costs of taking time away from other activities, such as foraging. Benefits may involve driving the predator to leave, teaching relatives to recognize predators, signaling quality to conspecifics, or others. An added layer of complexity in this system comes from the inter-specific interactions that often occur among different mobbing species (Magrath et al. 2014). This study by Salis et al. (2023) explored the responses of a local bird community to mobbing calls produced by individuals of two common mobbing species in European forests, coal tits, and crested tits. Not only did they compare responses to these two different species, they assessed the impact of the number of mobbing individuals on the stimulus recordings, and they did so at two very different times of the year with different social contexts for the birds involved, winter (non-breeding) and spring (breeding). The experiment was well-designed and highly powered, and the authors tested and confirmed an important assumption of their design, and thus the results are convincing. It is clear that members of the local bird community responded differently to the two different species, and this result raises interesting questions about why these species differed in their tendency to attract additional mobbers. For instance, are species that recruit more co-mobbers more effective at recruiting because they are more reliable in their mobbing behavior (Magrath et al. 2014), more likely to reciprocate (Krams and Krama, 2002), or for some other reason? Hopefully this system, now of proven utility thanks to the current study, will be useful for following up on hypotheses such as these. Other convincing results, such as the higher rate of mobbing response in winter than in spring, also merit following up with further work. Finally, their observation that playback of vocalizations of multiple individuals often elicited a more mobbing response that the playback of vocalizations of a single individual are interesting and consistent with other recent work indicating that groups of mobbers recruit more additional mobbers than do single mobbers (Dutour et al. 2021). However, as acknowledged in the manuscript, the design of the current study did not allow a distinction between the effect of multiple individuals signaling versus an effect of a stronger stimulus. Thus, this last result leaves the question of the effect of mobbing group size in these species open to further study. REFERENCES Dutour M, Kalb N, Salis A, Randler C (2021) Number of callers may affect the response to conspecific mobbing calls in great tits (Parus major). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 75, 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-02969-7 Krams I, Krama T (2002) Interspecific reciprocity explains mobbing behaviour of the breeding chaffinches, Fringilla coelebs. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 269, 2345–2350. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2155 Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN (2015) Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biological Reviews, 90, 560–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12122 Salis A, Lena JP, Lengagne T (2023) Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community. bioRxiv, 2022.05.05.490715, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.05.05.490715 | Acoustic cues and season affect mobbing responses in a bird community | Ambre Salis, Jean Paul Lena, Thierry Lengagne | <p>Heterospecific communication is common for birds when mobbing a predator. However, joining the mob should depend on the number of callers already enrolled, as larger mobs imply lower individual risks for the newcomer. In addition, some ‘communi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Community ecology, Social structure | Tim Parker | 2022-05-06 09:29:30 | View | ||

20 Jun 2024

Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitorsDiogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707We are better together: Spider mites running away from Cadmium contaminated plants make better decisions collectively than individuallyRecommended by Ruben Heleno based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Hyperaccumulator plants can concentrate heavy metals present on the soil in their tissues, avoiding their toxic effects and potentially discouraging herbivores (Martens & Boyd, 1994). But not all herbivores are necessarily discouraged, and access to locally abundant resources with low interspecific competition from other herbivores, can affect feeding choices. Godinho et al. performed a series of controlled laboratorial trials to evaluate if herbivores (spider mites) avoid tomato plants with high concentrations of Cadmium under alternative scenarios, namely: the presence/absence of conspecifics, the presence/absence of a competitor species (a congeneric mite), and the relative abundance of contaminated plants. They found that when looking for plants to lay their eggs, individual spider-mites (females) do not seem to discriminate between plants with or without cadmium, despite a significantly lower performance on the former. However, they consistently chose plants without Cadmium in set-ups where 200 mites are faced with this decision together. This preference was consistent and independent from the relative abundance of cadmium-free plants, but only when mites do this decision collectively. In addition, this preference was stronger than that for plants where interspecific competition was lower, with mites preferring to face high competition from congeneric herbivores than laying their eggs on Cadmium contaminated plants. Taken together these experiments suggest that aggregation is a key mechanism by which spider mites can avoid metal contaminated plants. As good research often does, these experiments open several important questions that will need to be addressed in the future. In particular, it will be important to clarify what are the sensorial and behavioural mechanisms that allow this decision/outcome when spider mites make this choice collectively but lead to a different outcome (no choice) when they face this decision alone. Additionally, it will be interesting to explore the potentially adaptive (or non-adaptive) consequences of this behaviour in terms of individual and inclusive fitness. One thing seems certain: both the abiotic and the biotic context can affect spider mite choices, and both need to be considered to advance our understanding about the trade-offs between plant defence mechanisms and associated herbivore decisions and fitness. References Martens, S. N., & Boyd, R. S. (1994). The ecological significance of nickel hyperaccumulation: a plant chemical defense. Oecologia, 98(3–4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00324227 Godinho, D. P., I. Fragata, M. C. de la Masseliere, S. Magalhaes 2024 Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors. bioRxiv, ver. 4, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology 2023.08.17.553707. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707

| Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors | Diogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes | <p>1. Plants can accumulate heavy metals from polluted soils on their shoots and use this to defend themselves against herbivory. One possible strategy for herbivores to cope with the reduction in performance imposed by heavy metal accumulation in... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Competition, Habitat selection, Herbivory | Ruben Heleno | 2023-11-09 11:52:58 | View | |

24 Mar 2023

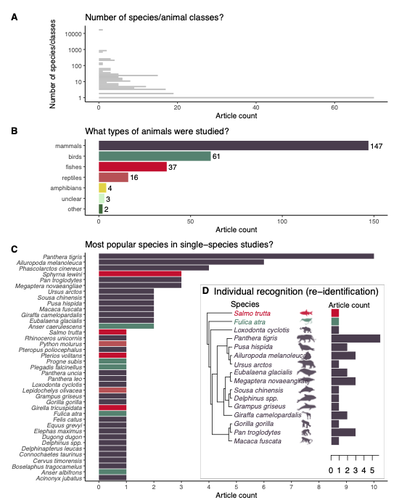

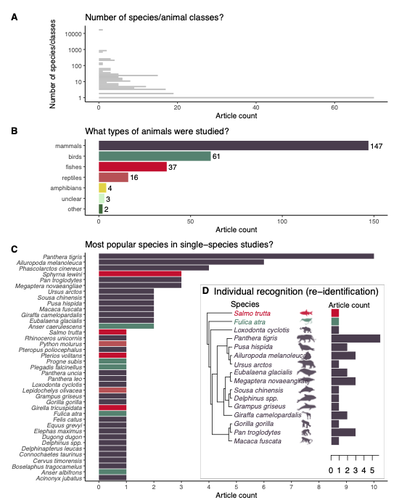

Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imageryShinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59DReview of machine learning uses for the analysis of images on wildlifeRecommended by Olivier Gimenez based on reviews by Falk Huettmann and 1 anonymous reviewerIn the field of ecology, there is a growing interest in machine (including deep) learning for processing and automatizing repetitive analyses on large amounts of images collected from camera traps, drones and smartphones, among others. These analyses include species or individual recognition and classification, counting or tracking individuals, detecting and classifying behavior. By saving countless times of manual work and tapping into massive amounts of data that keep accumulating with technological advances, machine learning is becoming an essential tool for ecologists. We refer to recent papers for more details on machine learning for ecology and evolution (Besson et al. 2022, Borowiec et al. 2022, Christin et al. 2019, Goodwin et al. 2022, Lamba et al. 2019, Nazir & Kaleem 2021, Perry et al. 2022, Picher & Hartig 2023, Tuia et al. 2022, Wäldchen & Mäder 2018). In their paper, Nakagawa et al. (2023) conducted a systematic review of the literature on machine learning for wildlife imagery. Interestingly, the authors used a method unfamiliar to ecologists but well-established in medicine called rapid review, which has the advantage of being quickly completed compared to a fully comprehensive systematic review while being representative (Lagisz et al., 2022). Through a rigorous examination of more than 200 articles, the authors identified trends and gaps, and provided suggestions for future work. Listing all their findings would be counterproductive (you’d better read the paper), and I will focus on a few results that I have found striking, fully assuming a biased reading of the paper. First, Nakagawa et al. (2023) found that most articles used neural networks to analyze images, in general through collaboration with computer scientists. A challenge here is probably to think of teaching computer vision to the generations of ecologists to come (Cole et al. 2023). Second, the images were dominantly collected from camera traps, with an increase in the use of aerial images from drones/aircrafts that raise specific challenges. Third, the species concerned were mostly mammals and birds, suggesting that future applications should aim to mitigate this taxonomic bias, by including, e.g., invertebrate species. Fourth, most papers were written by authors affiliated with three countries (Australia, China, and the USA) while India and African countries provided lots of images, likely an example of scientific colonialism which should be tackled by e.g., capacity building and the involvement of local collaborators. Last, few studies shared their code and data, which obviously impedes reproducibility. Hopefully, with the journals’ policy of mandatory sharing of codes and data, this trend will be reversed. REFERENCES Besson M, Alison J, Bjerge K, Gorochowski TE, Høye TT, Jucker T, Mann HMR, Clements CF (2022) Towards the fully automated monitoring of ecological communities. Ecology Letters, 25, 2753–2775. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.14123 Borowiec ML, Dikow RB, Frandsen PB, McKeeken A, Valentini G, White AE (2022) Deep learning as a tool for ecology and evolution. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 13, 1640–1660. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13901 Christin S, Hervet É, Lecomte N (2019) Applications for deep learning in ecology. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 1632–1644. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13256 Cole E, Stathatos S, Lütjens B, Sharma T, Kay J, Parham J, Kellenberger B, Beery S (2023) Teaching Computer Vision for Ecology. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2301.02211 Goodwin M, Halvorsen KT, Jiao L, Knausgård KM, Martin AH, Moyano M, Oomen RA, Rasmussen JH, Sørdalen TK, Thorbjørnsen SH (2022) Unlocking the potential of deep learning for marine ecology: overview, applications, and outlook†. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 79, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab255 Lagisz M, Vasilakopoulou K, Bridge C, Santamouris M, Nakagawa S (2022) Rapid systematic reviews for synthesizing research on built environment. Environmental Development, 43, 100730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2022.100730 Lamba A, Cassey P, Segaran RR, Koh LP (2019) Deep learning for environmental conservation. Current Biology, 29, R977–R982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.08.016 Nakagawa S, Lagisz M, Francis R, Tam J, Li X, Elphinstone A, Jordan N, O’Brien J, Pitcher B, Sluys MV, Sowmya A, Kingsford R (2023) Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2H59D Nazir S, Kaleem M (2021) Advances in image acquisition and processing technologies transforming animal ecological studies. Ecological Informatics, 61, 101212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2021.101212 Perry GLW, Seidl R, Bellvé AM, Rammer W (2022) An Outlook for Deep Learning in Ecosystem Science. Ecosystems, 25, 1700–1718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-022-00789-y Pichler M, Hartig F Machine learning and deep learning—A review for ecologists. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14061 Tuia D, Kellenberger B, Beery S, Costelloe BR, Zuffi S, Risse B, Mathis A, Mathis MW, van Langevelde F, Burghardt T, Kays R, Klinck H, Wikelski M, Couzin ID, van Horn G, Crofoot MC, Stewart CV, Berger-Wolf T (2022) Perspectives in machine learning for wildlife conservation. Nature Communications, 13, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27980-y Wäldchen J, Mäder P (2018) Machine learning for image-based species identification. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 2216–2225. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13075 | Rapid literature mapping on the recent use of machine learning for wildlife imagery | Shinichi Nakagawa, Malgorzata Lagisz, Roxane Francis, Jessica Tam, Xun Li, Andrew Elphinstone, Neil R. Jordan, Justine K. O’Brien, Benjamin J. Pitcher, Monique Van Sluys, Arcot Sowmya, Richard T. Kingsford | <p>1. Machine (especially deep) learning algorithms are changing the way wildlife imagery is processed. They dramatically speed up the time to detect, count, classify animals and their behaviours. Yet, we currently have a very few systematic liter... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Conservation biology | Olivier Gimenez | Anonymous | 2022-10-31 22:05:46 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle