Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Mar 2024

Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammalAmin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920Stress and stress hormones’ transmission from mothers to offspringRecommended by Matthieu Paquet based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Individuals can respond to environmental changes that they undergo directly (within-generation plasticity) but also through transgenerational plasticity, providing lasting effects that are transmitted to the next generations (Donelson et al. 2012; Munday et al. 2013; Kuijper & Hoyle 2015; Auge et al. 2017, Tariel et al. 2020). These parental effects can affect offspring via various mechanisms, notably via maternal transmission of hormones to the eggs or growing embryos (Mousseau & Fox 1998). While the effects of environmental quality may simply carry-over to the next generation (e.g., females in stressful environments give birth to offspring in poorer condition), parental effects may also be a mechanism that adjusts offspring phenotype in response to environmental variation and predictability, and thereby match offspring's phenotype to future environmental conditions (Gluckman et al. 2005; Marshall & Uller 2007; Dey et al. 2016; Yin et al. 2019), for example by preparing their offspring to an expected stressful environment. When females experience stress during gestation or egg formation, elevations in glucocorticoids (GC) are expected to affect offspring phenotype in many ways, from the offspring's own GC levels, to their growth and survival (Sheriff et al. 2017). This is a well established idea, but how strong is the evidence for this? A meta-analysis on birds found no clear effect of corticosterone manipulation on offspring traits (38 studies on 9 bird species for corticosterone manipulation; Podmokła et al. 2018). Another meta-analysis including 14 vertebrate species found no clear effect of prenatal stress on offspring GC (Thayer et al. 2018). Finally, a meta-analysis on wild vertebrates (23 species) found no clear effect of GC-mediated maternal effects on offspring traits (MacLeod et al. 2021). As often when facing such inconclusive results, context dependence has been suggested as one potential reason for such inconsistencies, for exemple sex specific effects (Groothuis et al. 2019, 2020). However, sex specific measures on offspring are scarce (Podmokła et al. 2018). Moreover, the literature available is still limited to a few, mostly “model” species. With their study, Amin et al. (2024) show the way to improve our understanding on GC transmission from mother to offspring and its effects in several aspects. First they used innovative non-invasive methods (which could broaden the range of species available to study) by quantifying cortisol metabolites from faecal samples collected from pregnant females, as proxy for maternal GC level, and relating it to GC levels from hairs of their neonate offspring. Second they used a free ranging large mammal (taxa from which literature is missing): the fallow deer (Dama dama). Third, they provide sex specific measures of GC levels. And finally but importantly, they are exemplary in their transparency regarding 1) the exploratory nature of their study, 2) their statistical thinking and procedure, and 3) the study limitations (e.g., low sample size and high within individual variation of measurements). I hope this study will motivate more research (on the fallow deer, and on other species) to broaden and strengthen our understanding of sex specific effects of maternal stress and CG levels on offspring phenotype and fitness. References Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., & Ciuti, S. (2024). Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and foetal glucocorticoids in a free-ranging large mammal. bioRxiv, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.04.538920 Auge, G.A., Leverett, L.D., Edwards, B.R. & Donohue, K. (2017). Adjusting phenotypes via within-and across-generational plasticity. New Phytologist, 216, 343–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14495 Dey, S., Proulx, S.R. & Teotonio, H. (2016). Adaptation to temporally fluctuating environments by the evolution of maternal effects. PLoS biology, 14, e1002388. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002388 Donelson, J.M., Munday, P.L., McCormick, M.I. & Pitcher, C.R. (2012). Rapid transgenerational acclimation of a tropical reef fish to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2, 30. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1323 Gluckman, P.D., Hanson, M.A. & Spencer, H.G. (2005). Predictive adaptive responses and human evolution. Trends in ecology & evolution, 20, 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.08.001 Groothuis, Ton GG, Bin-Yan Hsu, Neeraj Kumar, and Barbara Tschirren. "Revisiting mechanisms and functions of prenatal hormone-mediated maternal effects using avian species as a model." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 374, no. 1770 (2019): 20180115. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2018.0115 Groothuis, Ton GG, Neeraj Kumar, and Bin-Yan Hsu. "Explaining discrepancies in the study of maternal effects: the role of context and embryo." Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36 (2020): 185-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.10.006 Kuijper, B. & Hoyle, R.B. (2015). When to rely on maternal effects and when on phenotypic plasticity? Evolution, 69, 950–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12635 MacLeod, Kirsty J., Geoffrey M. While, and Tobias Uller. "Viviparous mothers impose stronger glucocorticoid‐mediated maternal stress effects on their offspring than oviparous mothers." Ecology and Evolution 11, no. 23 (2021): 17238-17259. Marshall, D.J. & Uller, T. (2007). When is a maternal effect adaptive? Oikos, 116, 1957–1963. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.16203.x Mousseau, T.A. & Fox, C.W. (1998). Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press. Munday, P.L., Warner, R.R., Monro, K., Pandolfi, J.M. & Marshall, D.J. (2013). Predicting evolutionary responses to climate change in the sea. Ecology Letters, 16, 1488–1500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12185 Podmokła, Edyta, Szymon M. Drobniak, and Joanna Rutkowska. "Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method–a meta‐analysis." Biological Reviews 93, no. 3 (2018): 1499-1517. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12406 Sheriff, M. J., Bell, A., Boonstra, R., Dantzer, B., Lavergne, S. G., McGhee, K. E., MacLeod, K. J., Winandy, L., Zimmer, C., & Love, O. P. (2017). Integrating ecological and evolutionary context in the study of maternal stress. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 57(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/icx105 Tariel, Juliette, Sandrine Plénet, and Émilien Luquet. "Transgenerational plasticity in the context of predator-prey interactions." Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8 (2020): 548660. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.548660 Thayer, Zaneta M., Meredith A. Wilson, Andrew W. Kim, and Adrian V. Jaeggi. "Impact of prenatal stress on offspring glucocorticoid levels: A phylogenetic meta-analysis across 14 vertebrate species." Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 4942. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-23169-w Yin, J., Zhou, M., Lin, Z., Li, Q.Q. & Zhang, Y.-Y. (2019). Transgenerational effects benefit offspring across diverse environments: a meta-analysis in plants and animals. Ecology letters, 22, 1976–1986. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13373 | Sex differences in the relationship between maternal and neonate cortisol in a free-ranging large mammal | Amin, B., Fishman, R., Quinn, M., Matas, D., Palme, R., Koren, L., Ciuti, S. | <p style="text-align: justify;">Maternal phenotypes can have long-term effects on offspring phenotypes. These maternal effects may begin during gestation, when maternal glucocorticoid (GC) levels may affect foetal GC levels, thereby having an orga... | Evolutionary ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Physiology, Zoology | Matthieu Paquet | 2023-06-05 09:06:56 | View | ||

26 Apr 2021

Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in EuropeOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dpA planned experiment on local adaptation in a host-parasite system: is adaptation to the host linked to its recent domestication?Recommended by Eric Petit based on reviews by Sharon Zytynska, Alex Stemmelen and 1 anonymous reviewerLocal adaptation shall occur whenever selective pressures vary across space and overwhelm the effects of gene flow and local extinctions (Kawecki and Ebert 2004). Because the intimate interaction that characterizes their relationship exerts a strong selective pressure on both partners, host-parasite systems represent a classical example in which local adaptation is expected from rapidly evolving parasites adapting to more evolutionary constrained hosts (Kaltz and Shykoff 1998). Such systems indeed represent a large proportion of the study-cases in local adaptation research (Runquist et al. 2020). Biotic interactions intervene in many environment-related societal challenges, so that understanding when and how local adaptation arises is important not only for understanding evolutionary dynamics but also for more applied questions such as the control of agricultural pests, biological invasions, or pathogens (Parker and Gilbert 2004). The exact conditions under which local adaptation does occur and can be detected is however still the focus of many theoretical, methodological and empirical studies (Blanquart et al. 2013, Hargreaves et al. 2020, Hoeksema and Forde 2008, Nuismer and Gandon 2008, Richardson et al. 2014). A recent review that evaluates investigations that examined the combined influence of biotic and abiotic factors on local adaptation reaches partial conclusions about their relative importance in different contexts and underlines the many traps that one has to avoid in such studies (Runquist et al. 2020). The authors of this review emphasize that one should evaluate local adaptation using wild-collected strains or populations and over multiple generations, on environmental gradients that span natural ranges of variation for both biotic and abiotic factors, in a theory-based hypothetico-deductive framework that helps interpret the outcome of experiments. These multiple targets are not easy to reach in each local adaptation experiment given the diversity of systems in which local adaptation may occur. Improving research practices may also help better understand when and where local adaptation does occur by adding controls over p-hacking, HARKing or publication bias, which is best achieved when hypotheses, date collection and analytical procedures are known before the research begins (Chambers et al. 2014). In this regard, the route taken by Olvera-Vazquez et al. (2021) is interesting. They propose to investigate whether the rosy aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) recently adapted to its cultivated host, the apple tree (Malus domestica), and chose to pre-register their hypotheses and planned experiments on PCI Ecology (Peer Community In 2020). Though not fulfilling all criteria mentioned by Runquist et al. (2020), they clearly state five hypotheses that all relate to the local adaptation of this agricultural pest to an economically important fruit tree, and describe in details a powerful, randomized experiment, including how data will be collected and analyzed. The experimental set-up includes comparisons between three sites located along a temperature transect that also differ in local edaphic and biotic factors, and contrasts wild and domesticated apple trees that originate from the three sites and were both planted in the local, sympatric site, and transplanted to allopatric sites. Beyond enhancing our knowledge on local adaptation, this experiment will also test the general hypothesis that the rosy aphid recently adapted to Malus sp. after its domestication, a question that population genetic analyses was not able to answer (Olvera-Vazquez et al. 2020). References Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2013) A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16, 1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12150 Briscoe Runquist RD, Gorton AJ, Yoder JB, Deacon NJ, Grossman JJ, Kothari S, Lyons MP, Sheth SN, Tiffin P, Moeller DA (2019) Context Dependence of Local Adaptation to Abiotic and Biotic Environments: A Quantitative and Qualitative Synthesis. The American Naturalist, 195, 412–431. https://doi.org/10.1086/707322 Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ, Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ (2014) Instead of “playing the game” it is time to change the rules: Registered Reports at <em>AIMS Neuroscience</em> and beyond. AIMS Neuroscience, 1, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2014.1.4 Hargreaves AL, Germain RM, Bontrager M, Persi J, Angert AL (2019) Local Adaptation to Biotic Interactions: A Meta-analysis across Latitudes. The American Naturalist, 195, 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1086/707323 Hoeksema JD, Forde SE (2008) A Meta‐Analysis of Factors Affecting Local Adaptation between Interacting Species. The American Naturalist, 171, 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/527496 Kaltz O, Shykoff JA (1998) Local adaptation in host–parasite systems. Heredity, 81, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00435.x Kawecki TJ, Ebert D (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 7, 1225–1241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2008) Moving beyond Common‐Garden and Transplant Designs: Insight into the Causes of Local Adaptation in Species Interactions. The American Naturalist, 171, 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1086/587077 Olvera-Vazquez SG, Remoué C, Venon A, Rousselet A, Grandcolas O, Azrine M, Momont L, Galan M, Benoit L, David G, Alhmedi A, Beliën T, Alins G, Franck P, Haddioui A, Jacobsen SK, Andreev R, Simon S, Sigsgaard L, Guibert E, Tournant L, Gazel F, Mody K, Khachtib Y, Roman A, Ursu TM, Zakharov IA, Belcram H, Harry M, Roth M, Simon JC, Oram S, Ricard JM, Agnello A, Beers EH, Engelman J, Balti I, Salhi-Hannachi A, Zhang H, Tu H, Mottet C, Barrès B, Degrave A, Razmjou J, Giraud T, Falque M, Dapena E, Miñarro M, Jardillier L, Deschamps P, Jousselin E, Cornille A (2020) Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa. bioRxiv, 2020.12.11.421644. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644 Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. (2021) Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) to its host (Malus domestica) and to its climate in Europe. In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dp, ver. 4. Parker IM, Gilbert GS (2004) The Evolutionary Ecology of Novel Plant-Pathogen Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 675–700. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132339 Peer Community In. (2020, January 15). Submit your preregistration to Peer Community In for peer review. https://peercommunityin.org/2020/01/15/submit-your-preregistration-to-peer-community-in-for-peer-review/ Richardson JL, Urban MC, Bolnick DI, Skelly DK (2014) Microgeographic adaptation and the spatial scale of evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.002 | Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in Europe | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T.,... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Understanding the extent of local adaptation in natural populations and the mechanisms enabling populations to adapt to their environment is a major avenue in ecology research. Host-parasite interaction is widely se... | Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations | Eric Petit | 2020-07-26 18:31:42 | View | ||

12 Apr 2023

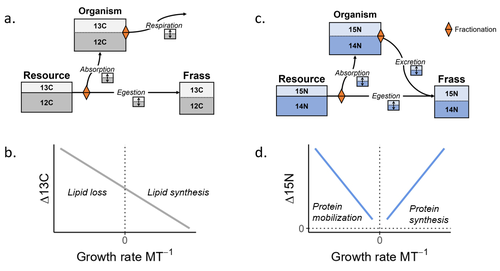

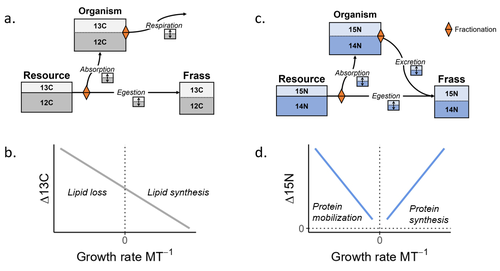

Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larvaSamuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573Refining our understanding how nutritional conditions affect 13C and 15N isotopic fractionation during ontogeny in a herbivorous insectRecommended by Gregor Kalinkat based on reviews by Anton Potapov and 1 anonymous reviewerUsing stable isotope fractionation to disentangle and understand the trophic positions of animals within the food webs they are embedded within has a long tradition in ecology (Post, 2002; Scheu, 2002). Recent years have seen increasing application of the method with several recent reviews summarizing past advancements in this field (e.g. Potapov et al., 2019; Quinby et al., 2020). In their new manuscript, Charberet and colleagues (2023) set out to refine our understanding of the processes that lead to nitrogen and carbon stable isotope fractionation by investigating how herbivorous insect larvae (specifically, the noctuid moth Spodoptera littoralis) respond to varying nutritional conditions (from starving to ad libitum feeding) in terms of stable isotopes enrichment. Though the underlying mechanisms have been experimentally investigated before in terrestrial invertebrates (e.g. in wolf spiders; Oelbermann & Scheu, 2002), the elegantly designed and adequately replicated experiments by Charberet and colleagues add new insights into this topic. Particularly, the authors provide support for the hypotheses that (A) 15N is disproportionately accumulated under fast growth rates (i.e. when fed ad libitum) and that (B) 13C is accumulated under low growth rates and starvation due to depletion of 13C-poor fat tissues. Applying this knowledge to field samples where feeding conditions are usually not known in detail is not straightforward, but the new findings could still help better interpretation of field data under specific conditions that make starvation for herbivores much more likely (e.g. droughts). Overall this study provides important methodological advancements for a better understanding of plant-herbivore interactions in a changing world. REFERENCES Charberet, S., Maria, A., Siaussat, D., Gounand, I., & Mathieu, J. (2023). Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.09.515573 Oelbermann, K., & Scheu, S. (2002). Stable Isotope Enrichment (δ 15N and δ 13C) in a Generalist Predator (Pardosa lugubris, Araneae: Lycosidae): Effects of Prey Quality. Oecologia, 130(3), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100813 Post, D. M. (2002). Using stable isotopes to estimate trophic position: Models, methods, and assumptions. Ecology, 83(3), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[0703:USITET]2.0.CO;2 Potapov, A. M., Tiunov, A. V., & Scheu, S. (2019). Uncovering trophic positions and food resources of soil animals using bulk natural stable isotope composition. Biological Reviews, 94(1), 37–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12434 Quinby, B. M., Creighton, J. C., & Flaherty, E. A. (2020). Stable isotope ecology in insects: A review. Ecological Entomology, 45(6), 1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12934 Scheu, S. (2002). The soil food web: Structure and perspectives. European Journal of Soil Biology, 38(1), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01117-7 | Feeding and growth variations affect δ13C and δ15N budgets during ontogeny in a lepidopteran larva | Samuel M. Charberet, Annick Maria, David Siaussat, Isabelle Gounand, Jérôme Mathieu | <p style="text-align: justify;">Isotopes are widely used in ecology to study food webs and physiology. The fractionation observed between trophic levels in nitrogen and carbon isotopes, explained by isotopic biochemical selectivity, is subject to ... |  | Experimental ecology, Food webs, Physiology | Gregor Kalinkat | 2022-11-16 15:23:31 | View | |

06 May 2021

Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changesThibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021A lack of clear dietary differences between ontogenetic stages of invasive slippersnails provides important insights into resource use and potential inter- and intra-specific competitionRecommended by Matthew Bracken based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersThe slippersnail (Crepidula fornicata), originally from the eastern coast of North America, has invaded European coastlines from Norway to the Mediterranean Sea [1]. This species is capable of achieving incredibly high densities (up to several thousand individuals per square meter) and likely has major impacts on a variety of community- and ecosystem-level processes, including alteration of carbon and nitrogen fluxes and competition with native suspension feeders [2]. Given this potential for competition, it is important to understand the diet of C. fornicata and its potential overlap with native species. However, previous research on the diet of C. fornicata and related species suggests that the types of food consumed may change with age [3, 4]. This species has an unusual reproductive strategy. It is a sequential hermaphrodite, which begins life as a somewhat mobile male but eventually slows down to become sessile. Sessile individuals form stacks of up to 10 or more individuals, with larger individuals on the bottom of the stack, and decreasingly smaller individuals piled on top. Snails at the bottom of the stack are female, whereas snails at the top of the stack are male; when the females die, the largest males become female [5]. Thus, understanding these potential ontogenetic dietary shifts has implications for both intraspecific (juvenile vs. male vs. female) and interspecific competition associated with an abundant, invasive species. To this end, Androuin and colleagues evaluated the stable-isotope (d13C and d15N) and fatty-acid profiles of food sources and different life-history stages of C. fornicata [6]. Based on previous work highlighting the potential for life-history changes in the diet of this species [3,4], they hypothesized that C. fornicata would shift its diet as it aged and predicted that this shift would be reflected in changes in its stable-isotope and fatty-acid profiles. The authors found that potential food sources (biofilm, suspended particulate organic matter, and superficial sedimentary organic matter) differed substantially in both stable-isotope and fatty-acid signatures. However, whereas fatty-acid profiles changed substantially with age, there was no shift in the stable-isotope signatures. Because stable-isotope differences between food sources were not reflected in differences between life-history stages, the authors conservatively concluded that there was insufficient evidence for a diet shift with age. The ontogenetic shifts in fatty-acid profiles were intriguing, but the authors suggested that these reflected age-related physiological changes rather than changes in diet. The authors’ work highlights the need to consider potential changes in the roles of invasive species with age, especially when evaluating interactions with native species. In this case, C. fornicata consumed a variety of food sources, including both benthic and particulate organic matter, regardless of age. The carbon stable-isotope signature of C. fornicata overlaps with those of several native suspension- and deposit-feeding species in the region [7], suggesting the possibility of resource competition, especially given the high abundances of this invader. This contribution demonstrates the potential difficulty of characterizing the impacts of an abundant invasive species with a complex life-history strategy. Like many invasive species, C. fornicata appears to be a dietary generalist, which likely contributes to its success in establishing and thriving in a variety of locations [8].

References [1] Blanchard M (1997) Spread of the slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L. 1758) in Europe. Current state dans consequences. Scientia Marina, 61, 109–118. Open Access version : https://archimer.ifremer.fr/doc/00423/53398/54271.pdf [2] Martin S, Thouzeau G, Chauvaud L, Jean F, Guérin L, Clavier J (2006) Respiration, calcification, and excretion of the invasive slipper limpet, Crepidula fornicata L.: Implications for carbon, carbonate, and nitrogen fluxes in affected areas. Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 1996–2007. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.1996 [3] Navarro JM, Chaparro OR (2002) Grazing–filtration as feeding mechanisms in motile specimens of Crepidula fecunda (Gastropoda: Calyptraeidae). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 270, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00013-8 [4] Yee AK, Padilla DK (2015) Allometric Scaling of the Radula in the Atlantic Slippersnail Crepidula fornicata. Journal of Shellfish Research, 34, 903–907. https://doi.org/10.2983/035.034.0320 [5] Collin R (1995) Sex, Size, and Position: A Test of Models Predicting Size at Sex Change in the Protandrous Gastropod Crepidula fornicata. The American Naturalist, 146, 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1086/285826 [6] Androuin T, Dubois SF, Hubas C, Lefebvre G, Grand FL, Schaal G, Carlier A (2021) Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.229021, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.229021 [7] Dauby P, Khomsi A, Bouquegneau J-M (1998) Trophic Relationships within Intertidal Communities of the Brittany Coasts: A Stable Carbon Isotope Analysis. Journal of Coastal Research, 14, 1202–1212. Retrieved May 4, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/4298880 [8] Machovsky-Capuska GE, Senior AM, Simpson SJ, Raubenheimer D (2016) The Multidimensional Nutritional Niche. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 31, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.009

| Trophic niche of the invasive gregarious species Crepidula fornicata, in relation to ontogenic changes | Thibault Androuin, Stanislas F. Dubois, Cédric Hubas, Gwendoline Lefebvre, Fabienne Le Grand, Gauthier Schaal, Antoine Carlier | <p style="text-align: justify;">The slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata is a common and widespread invasive gregarious species along the European coast. Among its life-history traits, well-documented ontogenic changes in behavior (i.e., motile male... |  | Food webs, Life history, Marine ecology | Matthew Bracken | 2020-08-01 23:55:57 | View | |

20 Jun 2019

Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predatorChristophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel https://doi.org/10.1101/472431Sexual segregation in a sexually dimorphic seabird: a matter of spatial scaleRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by Dries Bonte and 1 anonymous reviewerSexual segregation appears in many taxa and can have important ecological, evolutionary and conservation implications. Sexual segregation can take two forms: either the two sexes specialise in different habitats but share the same area (habitat segregation), or they occupy the same habitat but form separate, unisex groups (social segregation) [1,2]. Segregation would have evolved as a way to avoid, or at least, reduce intersexual competition. References [1] Conradt, L. (2005). Definitions, hypotheses, models and measures in the study of animal segregation. In Sexual segregation in vertebrates: ecology of the two sexes (Ruckstuhl K.E. and Neuhaus, P. eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Pp:11–34. | Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predator | Christophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel | <p>Sexual segregation is common in many species and has been attributed to intra-specific competition, sex-specific differences in foraging efficiency or in activity budgets and habitat choice. However, very few studies have simultaneously quantif... |  | Foraging, Marine ecology | Denis Réale | Dries Bonte, Anonymous | 2018-11-19 13:40:59 | View |

25 Nov 2022

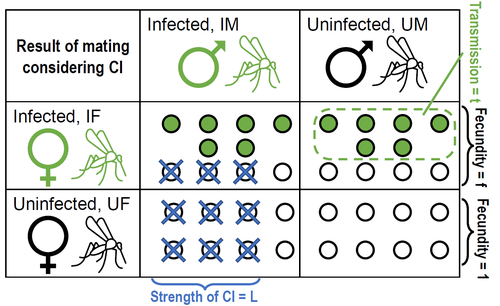

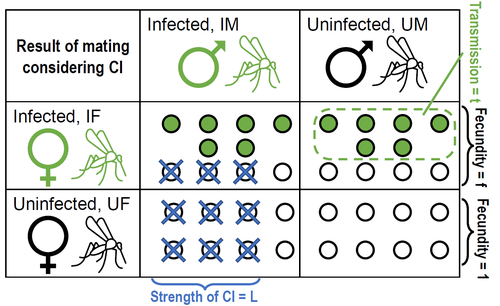

Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populationsPetteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824Population dynamics of Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeRecommended by Jorge Peña based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers"Good and evil are so close as to be chained together in the soul" Maternally inherited symbionts—microorganisms that pass from a female host to her progeny—have two main ways of increasing their own fitness. First, they can increase the fecundity or viability of infected females. This “positive fitness effects” strategy is the one commonly used by mutualistic symbionts, such as Buchnera aphidicola—the bacterial endosymbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum [4]. Second, maternally inherited symbionts can manipulate the reproduction of infected females in a way that enhances symbiont transmission at the expense of host fitness. A famous example of this “reproductive parasitism” strategy is the cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) [3] induced by bacteria of the genus Wolbachia in their arthropod and nematode hosts. CI works as a toxin-antidote system, whereby the sperm of infected males is modified in a lethal way (toxin) that can only be reverted if the egg is also infected (antidote) [1]. As a result, CI imposes a kind of conditional sterility on their hosts: while infected females are compatible with both infected and uninfected males, uninfected females experience high offspring mortality if (and only if) they mate with infected males [7]. These two symbiont strategies (positive fitness effects versus reproductive parasitism) have been traditionally studied separately, both empirically and theoretically. However, it has become clear that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive, and that a reproductive parasite can simultaneously act as a mutualist—an infection type that has been dubbed “Jekyll and Hyde” [6], after the famous novella by Robert Louis Stevenson about kind scientist Dr. Jekyll and his evil alter ego, Mr. Hyde. In important previous work, Zug and Hammerstein [7] analyzed the consequences of positive fitness effects on the dynamics of different kind of infections, including “Jekyll and Hyde” infections characterized by CI and other reproductive parasitism strategies. Building on this and related modeling framework, Karisto et al. [2] re-investigate and expand on the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism in Wolbachia infections by focusing on CI in both diplodiploid and haplodiploid populations, and by paying particular attention to the mathematical assumption structure underlying their results. Karisto et al. begin by reviewing classic models of Wolbachia infections in diplodiploid populations that assume a “negative fitness effect” (modeled as a fertility penalty on infected females), characteristic of a pure strategy of reproductive parasitism. Together with the positive frequency-dependent effects due to CI (whereby the fitness benefits to symbionts infecting females increase with the proportion of infected males in the population) this results in population dynamics characterized by two stable equilibria (the Wolbachia-free state and an interior equilibrium with a high frequency of Wolbachia-carrying hosts) separated by an unstable interior equilibrium. Wolbachia can then spread once the initial frequency is above a threshold or an invasion barrier, but is prevented from fixing by a proportion of infections failing to be passed on to offspring. Karisto et al. show that, given the assumption of negative fitness effects, the stable interior equilibrium can never feature a Wolbachia prevalence below one-half. Moreover, they convincingly argue that a prevalence greater than but close to one-half is difficult to maintain in the presence of stochastic fluctuations, as in these cases the high-prevalence stable equilibrium would be too close to the unstable equilibrium signposting the invasion barrier. Karisto et al. then relax the assumption of negative fitness effects and allow for positive fitness effects (modeled as a fertility premium on infected females) in a diplodiploid population. They show that positive fitness effects may result in situations where the original invasion threshold is now absent, the bistable coexistence dynamics are transformed into purely co-existence dynamics, and Wolbachia symbionts can now invade when rare. Karisto et al. conclude that positive fitness effects provide a plausible and potentially testable explanation for the low frequencies of symbiont-carrying hosts that are sometimes observed in nature, which are difficult to reconcile with the assumption of negative fitness effects. Finally, Karisto et al. extend their analysis to haplodiploid host populations (where all fertilized eggs develop as females). Here, they investigate two types of cytoplasmic incompatibility: a female-killing effect, similar to the CI effect studied in diplodiploid populations (the “Leptopilina type” of Vavre et al. [5]) and a masculinization effect, where CI leads to the loss of paternal chromosomes and to the development of the offspring as a male (the “Nasonia type” of Vavre et al. [5]). The models are now two-sex, which precludes a complete analytical treatment, in particular regarding the stability of fixed points. Karisto et al. compensate by conducting large numerical analyses that support their claims. Importantly, all main conclusions regarding the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism continue to hold under haplodiploidy. All in all, the analysis and results by Karisto et al. suggest that it is not necessary to resort to classical (but depending on the situation, unlikely) mechanisms, such as ongoing invasion or source-sink dynamics, to explain arthropod populations featuring low-prevalent Wolbachia infections. Instead, low-frequency equilibria might be simply due to reproductive parasites conferring beneficial fitness effects, or Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll (positive fitness effects) and Mr. Hyde (cytoplasmatic incompatibility). References [1] Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, Weill M, Sicard M, Charlat S (2019) The Toxin–Antidote Model of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Genetics and Evolutionary Implications. Trends in Genetics, 35, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2018.12.004 [2] Karisto P, Duplouy A, Vries C de, Kokko H (2022) Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations. bioRxiv, 2022.04.11.487824, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824 [3] Laven H (1956) Cytoplasmic Inheritance in Culex. Nature, 177, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/177141a0 [4] Perreau J, Zhang B, Maeda GP, Kirkpatrick M, Moran NA (2021) Strong within-host selection in a maternally inherited obligate symbiont: Buchnera and aphids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2102467118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102467118 [5] Vavre F, Fleury F, Varaldi J, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M (2000) Evidence for Female Mortality in Wolbachia-Mediated Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Haplodiploid Insects: Epidemiologic and Evolutionary Consequences. Evolution, 54, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00019.x [6] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2015) Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biological Reviews, 90, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12098 [7] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2018) Evolution of reproductive parasites with direct fitness benefits. Heredity, 120, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0022-5 | Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations | Petteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">The bacterial endosymbiont <em>Wolbachia</em> is best known for its ability to modify its host’s reproduction by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) to facilitate its own spread. Classical models predict eithe... |  | Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology | Jorge Peña | 2022-04-12 12:52:55 | View | |

06 Dec 2019

Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslandsNatasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2543768The role of phenology for determining plant-pollinator interactions along a latitudinal gradientRecommended by Anna Eklöf based on reviews by Ignasi Bartomeus, Phillip P.A. Staniczenko and 1 anonymous reviewerIncreased knowledge of what factors are determining species interactions are of major importance for our understanding of dynamics and functionality of ecological communities [1]. Currently, when ongoing temperature modifications lead to changes in species temporal and spatial limits the subject gets increasingly topical. A species phenology determines whether it thrive or survive in its environment. However, as the phenologies of different species are not necessarily equally affected by environmental changes, temporal or spatial mismatches can occur and affect the species-species interactions in the network [2] and as such the full network structure. References [1] Pascual, M., and Dunne, J. A. (Eds.). (2006). Ecological networks: linking structure to dynamics in food webs. Oxford University Press. | Does phenology explain plant-pollinator interactions at different latitudes? An assessment of its explanatory power in plant-hoverfly networks in French calcareous grasslands | Natasha de Manincor, Nina Hautekeete, Yves Piquot, Bertrand Schatz, Cédric Vanappelghem, François Massol | <p>For plant-pollinator interactions to occur, the flowering of plants and the flying period of pollinators (i.e. their phenologies) have to overlap. Yet, few models make use of this principle to predict interactions and fewer still are able to co... |  | Interaction networks, Pollination, Statistical ecology | Anna Eklöf | 2019-01-18 19:02:13 | View | |

10 Jan 2019

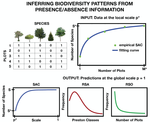

Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrencesAnna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan https://doi.org/10.1101/387456Upscaling the neighborhood: how to get species diversity, abundance and range distributions from local presence/absence dataRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer

How do you estimate the biodiversity of a whole community, or the distribution of abundances and ranges of its species, from presence/absence data in scattered samples? ADDITIONAL COMMENTS 1) To explain the novelty of the authors' contribution, it is useful to look at competing techniques. 2) The main condition for all such approaches to work is well-mixedness: each sample should be sufficiently like a lot drawn from the same skewed lottery. As long as that condition applies, finding the best approach is a theoretical matter of probabilities and combinatorics that may, in time, be given a definite answer. 3) One may ask: why the Negative Binomial as a Species Abundance Distribution? References [1] Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S., & Williams, C. B. (1943). The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 42-58. doi: 10.2307/1411 | Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences | Anna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan | <p>Biodiversity provides support for life, vital provisions, regulating services and has positive cultural impacts. It is therefore important to have accurate methods to measure biodiversity, in order to safeguard it when we discover it to be thre... |  | Macroecology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2018-08-09 16:44:09 | View | |

21 Feb 2019

Photosynthesis of Laminaria digitata during the immersion and emersion periods of spring tidal cycles during hot, sunny weatherAline Migné, Gaspard Delebecq, Dominique Davoult, Nicolas Spilmont, Dominique Menu, Marie-Andrée Janquin and François Gévaert https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-01827565v4Evaluating physiological responses of a kelp to environmental changes at its vulnerable equatorward range limitRecommended by Matthew Bracken based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersUnderstanding processes at species’ range limits is of paramount importance in an era of global change. For example, the boreal kelp Laminaria digitata, which dominates low intertidal and shallow subtidal rocky reefs in northwestern Europe, is declining in the equatorward portion of its range [1]. In this contribution, Migné and colleagues [2] focus on L. digitata near its southern range limit on the coast of France and use a variety of techniques to paint a complete picture of the physiological responses of the kelp to environmental changes. Importantly, and in contrast to earlier work on the species which focused on subtidal individuals (e.g. [3]), Migné et al. [2] describe responses not only in the most physiologically stressful portion of the species’ range but also in the most stressful portion of its local environment: the upper portion of its zone on the shoreline, where it is periodically exposed to aerial conditions and associated thermal and desiccation stresses. References [1] Raybaud, V., Beaugrand, G., Goberville, E., Delebecq, G., Destombe, C., Valero, M., Davoult, D., Morin, P. & Gevaert, F. (2013). Decline in kelp in west Europe and climate. PloS one, 8(6), e66044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066044 | Photosynthesis of Laminaria digitata during the immersion and emersion periods of spring tidal cycles during hot, sunny weather | Aline Migné, Gaspard Delebecq, Dominique Davoult, Nicolas Spilmont, Dominique Menu, Marie-Andrée Janquin and François Gévaert | The boreal kelp Laminaria digitata dominates the low intertidal and upper subtidal zones of moderately exposed rocky shores in north-western Europe. Due to ocean warming, this foundation species is predicted to disappear from French coasts in the ... |  | Marine ecology | Matthew Bracken | 2018-07-02 18:03:11 | View | |

02 Aug 2021

Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimationAline Migné, Gwendoline Duong, Dominique Menu, Dominique Davoult & François Gévaert https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03079617Towards a better understanding of the effects of self-shading on Fucus serratus populationsRecommended by Cédric Hubas based on reviews by Gwenael Abril, Francesca Rossi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Gwenael Abril, Francesca Rossi and 1 anonymous reviewer

The importance of the vertical structure of vegetation cover for the functioning, management and conservation of ecosystems has received particular attention from ecologists in the last decades. Canopy architecture has many implications for light extinction coefficient, temperature variation reduction, self-shading which are all key parameters for the structuring and functioning of different ecosystems such as grasslands [1,2], forests [3,4], phytoplankton communities [5, 6], macroalgal populations [7] and even underwater animal forests such as octocoral communities [8]. This research topic, therefore, benefits from a large body of literature and the facilitative role of self-shadowing is no longer in question. However, it is always puzzling to note that some of the most common ecosystems turn out to be amongst the least known. This is precisely the case of the Fucus serratus communities which are widespread in Northeast Atlantic along the Atlantic coast of Europe from Svalbard to Portugal, as well as Northwest Atlantic & Gulf of St. Lawrence, easily accessible at low tide, but which have comparatively received less attention than more emblematic macro-algal communities such as Laminariales. The lack of attention paid to these most common Fucales is particularly critical as some species such as F. serratus are proving to be particularly vulnerable to environmental change, leading to a predicted northward retreat from its current southern boundary [9]. In the present study [10], the authors showed the importance of the vegetation cover in resisting tide-induced environmental stresses. The canopy of F. serratus mitigates stress levels experienced in the lower layers during emersion, while various acclimation strategies take over to maintain the photosynthetic apparatus in optimal conditions. They hereby highlight adaptation mechanisms to the extreme environment represented by the intertidal zone. These adaptation strategies were expected and similar mechanisms had been shown at the cellular level previously [11]. The earliest studies on the subject have shown that the structure of the bottom, the movement of water, and light availability all "influence the distribution of Fucaceae and disturb the regularity of their fine zonation, which itself is caused by the most important factor, desiccation", as Zaneveld states in his review [12]. He observed that the causes of the zonal distribution of marine algae are numerous, and identified several points of interest such as the relative period of emersion, the rapidity of desiccation, the loss of water, and the thickness of the cell walls. The present study thus highlights the existence of facilitative mechanisms associated with F. serratus canopy and nicely confirms previous work with in situ observations. It also highlights the importance of the vegetative cover in combating desiccation and introduces the dampening effect as a facilitating mechanism. The effect of the vegetation cover can sometimes even be felt beyond its immediate area of influence. A recent study shows that ground-level ozone is significantly reduced by the combined effects of canopy shading and turbulence [4]. Below the canopy, the light intensity becomes sufficiently low which inhibits ozone formation due to the decrease in the rates of hydroxyl radical formation and the rates of conversion of nitrogen dioxide to nitrogen oxide by photolysis. In addition, reductions in light levels associated with foliage promote ozone-destroying reactions between plant-emitted species, such as nitric oxide and/or alkenes, and ozone itself. The reduction in diffusivity slows the upward transport of surface emitted species, partially decoupling the area under the canopy from the rest of the atmosphere. By analogy with the work of Makar et al [4], and in the light of the results provided by the authors of this study, one may wonder whether the canopy dampening of F. serratus communities (and other common fucoids widely distributed on our coasts) might not also influence atmospheric chemistry, both at the Earth's surface and in the atmospheric boundary layer. The lack of accumulation of reactive oxygen species under the canopy found by the authors is consistent with this hypothesis and suggests that the damping effect of F. serratus may well have much wider consequences than expected. References [1] Jurik TW, Kliebenstein H (2000) Canopy Architecture, Light Extinction and Self-Shading of a Prairie Grass, Andropogon Gerardii. The American Midland Naturalist, 144, 51–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3083010 [2] Mitchley J, Willems JH (1995) Vertical canopy structure of Dutch chalk grasslands in relation to their management. Vegetatio, 117, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00033256 [3] Kane VR, Gillespie AR, McGaughey R, Lutz JA, Ceder K, Franklin JF (2008) Interpretation and topographic compensation of conifer canopy self-shadowing. Remote Sensing of Environment, 112, 3820–3832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2008.06.001 [4] Makar PA, Staebler RM, Akingunola A, Zhang J, McLinden C, Kharol SK, Pabla B, Cheung P, Zheng Q (2017) The effects of forest canopy shading and turbulence on boundary layer ozone. Nature Communications, 8, 15243. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15243 [5] Shigesada N, Okubo A (1981) Analysis of the self-shading effect on algal vertical distribution in natural waters. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 12, 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00276919 [6] Barros MP, Pedersén M, Colepicolo P, Snoeijs P (2003) Self-shading protects phytoplankton communities against H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 30, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.3354/ame030275 [7] Ørberg SB, Krause-Jensen D, Mouritsen KN, Olesen B, Marbà N, Larsen MH, Blicher ME, Sejr MK (2018) Canopy-Forming Macroalgae Facilitate Recolonization of Sub-Arctic Intertidal Fauna and Reduce Temperature Extremes. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00332 [8] Nelson H, Bramanti L (2020) From Trees to Octocorals: The Role of Self-Thinning and Shading in Underwater Animal Forests. In: Perspectives on the Marine Animal Forests of the World (eds Rossi S, Bramanti L), pp. 401–417. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57054-5_12 [9] Jueterbock A, Kollias S, Smolina I, Fernandes JMO, Coyer JA, Olsen JL, Hoarau G (2014) Thermal stress resistance of the brown alga Fucus serratus along the North-Atlantic coast: Acclimatization potential to climate change. Marine Genomics, 13, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2013.12.008 [10] Migné A, Duong G, Menu D, Davoult D, Gévaert F (2021) Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimation. HAL, hal-03079617, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03079617 [11] Lichtenberg M, Kühl M (2015) Pronounced gradients of light, photosynthesis and O2 consumption in the tissue of the brown alga Fucus serratus. New Phytologist, 207, 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13396 [12] Zaneveld JS (1937) The Littoral Zonation of Some Fucaceae in Relation to Desiccation. Journal of Ecology, 25, 431–468. https://doi.org/10.2307/2256204 | Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimation | Aline Migné, Gwendoline Duong, Dominique Menu, Dominique Davoult & François Gévaert | <p style="text-align: justify;">The brown alga <em>Fucus serratus</em> forms dense stands on the sheltered low intertidal rocky shores of the Northeast Atlantic coast. In the southern English Channel, these stands have proved to be highly producti... |  | Marine ecology | Cédric Hubas | 2021-01-05 16:24:02 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle