Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

13 May 2024

Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in MetacommunitiesMatthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.04.543606Beyond pairwise species interactions: coarser inference of their joined effects is more relevantRecommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler based on reviews by Frederik De Laender, Hao Ran Lai and Malyon Bimler

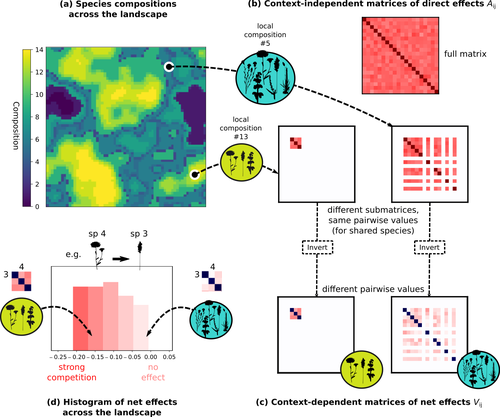

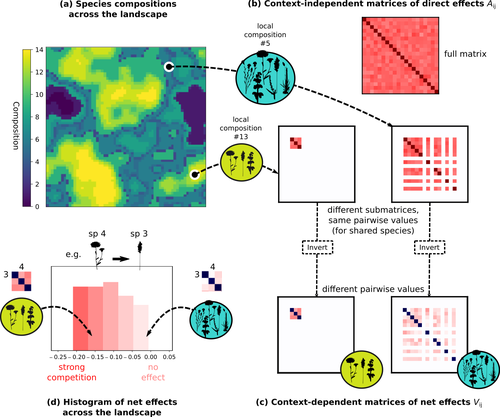

Barbier et al. (2024) investigated the dynamics of species abundances depending on their ecological niche (abiotic component) and on (numerous) competitive interactions. In line with previous evidence and expectations (Barbier et al. 2018), the authors show that it is possible to robustly infer the mean and variance of interaction coefficients from species co-distributions, while it is not possible to infer the individual coefficient values. The authors devised a simulation framework representing multispecies dynamics in an heterogeneous environmental context (2D grid landscape). They used a Lotka-Volterra framework involving pairwise interaction coefficients and species-specific carrying capacities. These capacities depend on how well the species niche matches the local environmental conditions, through a Gaussian function of the distance of the species niche centers to the local environmental values. They considered two contrasted scenarios denoted as « Environmental tracking » and « Dispersal limited ». In the latter case, species are initially seeded over the environmental grid and cannot disperse to other cells, while in the former case they can disperse and possibly be more performant in other cells. The direct effects of species on one another are encoded in an interaction matrix A, and the authors further considered net interactions depending on the inverse of the matrix of direct interactions (Zelnik et al., 2024). The net effects are context-dependent, i.e., it involves the environment-dependent biotic capacities, even through the interaction terms can be defined between species as independent from local environment. The results presented here underline that the outcome of many individual competitive interactions can only be understood in terms of macroscopic properties. In essence, the results here echoe the mean field theories that investigate the dynamics of average ecological properties instead of the microscopic components (e.g., McKane et al. 2000). In a philosophical perspective, community ecology has long struggled with analyzing and inferring local determinants of species coexistence from species co-occurrence patterns, so that it was claimed that no universal laws can be derived in the discipline (Lawton 1999). Using different and complementary methods and perspectives, recent research has also shown that species assembly parameter values cannot be unambiguously inferred from species co-occurrences only, even in simple designs where an equilibrium can be reached (Poggiato et al. 2021). Although the roles of high-order competitive interactions and intransivity can lead to species coexistence, the simple view of a single loop of competitive interactions is easily challenged when further interactions and complexity is added (Gallien et al. 2024). But should we put so much emphasis on inferring individual interaction coefficients? In a quest to understand the emerging properties of elementary processes, ecological theory could go forward with a more macroscopic analysis and understanding of species coexistence in many communities. The authors referred several times to an interesting paper from Schaffer (1981), entitled « Ecological abstraction: the consequences of reduced dimensionality in ecological models ». It proposes that estimating individual species competition coefficients is not possible, but that competition can be assessed at the coarser level of organisation, i.e., between ecological guilds. This idea implies that the dimensionality of the competition equations should be greatly reduced to become tractable in practice. Taking together this claim with the results of the present Barbier et al. (2024) paper, it becomes clearer that the nature of competitive interactions can be addressed through « abstracted » quantities, as those of guilds or the moments of the individual competition coefficients (here the average and the standard deviation). Therefore the scope of Barbier et al. (2024) framework goes beyond statistical issues in parameter inference, but question the way we must think and represent the numerous competitive interactions in a simplified and robust way. References Barbier, Matthieu, Jean-François Arnoldi, Guy Bunin, et Michel Loreau. 2018. « Generic assembly patterns in complex ecological communities ». Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (9): 2156‑61. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710352115 | Getting More by Asking for Less: Linking Species Interactions to Species Co-Distributions in Metacommunities | Matthieu Barbier, Guy Bunin, Mathew A. Leibold | <p>AbstractOne of the more difficult challenges in community ecology is inferring species interactions on the basis of patterns in the spatial distribution of organisms. At its core, the problem is that distributional patterns reflect the ‘realize... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Competition, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | François Munoz | 2023-10-21 14:14:16 | View | |

20 Jun 2024

Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitorsDiogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707We are better together: Spider mites running away from Cadmium contaminated plants make better decisions collectively than individuallyRecommended by Ruben Heleno based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Hyperaccumulator plants can concentrate heavy metals present on the soil in their tissues, avoiding their toxic effects and potentially discouraging herbivores (Martens & Boyd, 1994). But not all herbivores are necessarily discouraged, and access to locally abundant resources with low interspecific competition from other herbivores, can affect feeding choices. Godinho et al. performed a series of controlled laboratorial trials to evaluate if herbivores (spider mites) avoid tomato plants with high concentrations of Cadmium under alternative scenarios, namely: the presence/absence of conspecifics, the presence/absence of a competitor species (a congeneric mite), and the relative abundance of contaminated plants. They found that when looking for plants to lay their eggs, individual spider-mites (females) do not seem to discriminate between plants with or without cadmium, despite a significantly lower performance on the former. However, they consistently chose plants without Cadmium in set-ups where 200 mites are faced with this decision together. This preference was consistent and independent from the relative abundance of cadmium-free plants, but only when mites do this decision collectively. In addition, this preference was stronger than that for plants where interspecific competition was lower, with mites preferring to face high competition from congeneric herbivores than laying their eggs on Cadmium contaminated plants. Taken together these experiments suggest that aggregation is a key mechanism by which spider mites can avoid metal contaminated plants. As good research often does, these experiments open several important questions that will need to be addressed in the future. In particular, it will be important to clarify what are the sensorial and behavioural mechanisms that allow this decision/outcome when spider mites make this choice collectively but lead to a different outcome (no choice) when they face this decision alone. Additionally, it will be interesting to explore the potentially adaptive (or non-adaptive) consequences of this behaviour in terms of individual and inclusive fitness. One thing seems certain: both the abiotic and the biotic context can affect spider mite choices, and both need to be considered to advance our understanding about the trade-offs between plant defence mechanisms and associated herbivore decisions and fitness. References Martens, S. N., & Boyd, R. S. (1994). The ecological significance of nickel hyperaccumulation: a plant chemical defense. Oecologia, 98(3–4), 379–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00324227 Godinho, D. P., I. Fragata, M. C. de la Masseliere, S. Magalhaes 2024 Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors. bioRxiv, ver. 4, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology 2023.08.17.553707. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.08.17.553707

| Spider mites collectively avoid plants with cadmium irrespective of their frequency or the presence of competitors | Diogo Prino Godinho*, Ines Fragata*, Maud Charlery de la Masseliere, Sara Magalhaes | <p>1. Plants can accumulate heavy metals from polluted soils on their shoots and use this to defend themselves against herbivory. One possible strategy for herbivores to cope with the reduction in performance imposed by heavy metal accumulation in... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Competition, Habitat selection, Herbivory | Ruben Heleno | 2023-11-09 11:52:58 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

18 Apr 2024

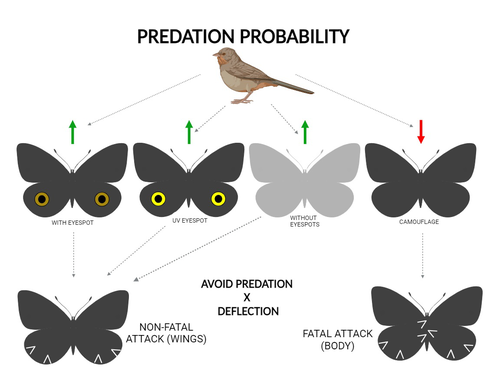

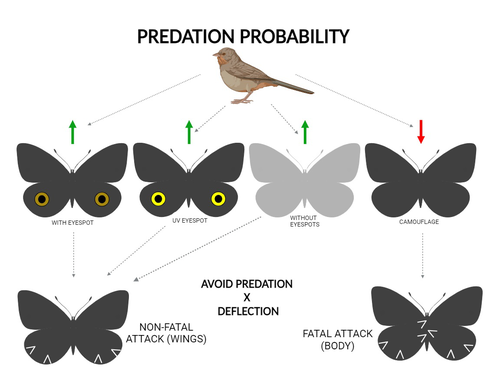

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

28 Mar 2024

Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (Salmo trutta) population in northern FranceQuentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.21.568009Why are trout getting smaller?Recommended by Aleksandra Walczyńska based on reviews by Jan Kozlowski and 1 anonymous reviewerDecline in body size over time have been widely observed in fish (but see Solokas et al. 2023), and the ecological consequences of this pattern can be severe (e.g., Audzijonyte et al. 2013, Oke et al. 2020). Therefore, studying the interrelationships between life history traits to understand the causal mechanisms of this pattern is timely and valuable. This phenomenon was the subject of a study by Josset et al. (2024), in which the authors analysed data from 39 years of trout trapping in the Bresle River in France. The authors focused mainly on the length of trout on their first return from the sea. The most important results of the study were the decrease in fish length-at-first return and the change in the age structure of first-returning trout towards younger (and earlier) returning fish. It seems then that the smaller size of trout is caused by a shorter time spent in the sea rather than a change in a growth pattern, as length-at-age remained relatively constant, at least for those returning earlier. Fish returning after two years spent in the sea had a relatively smaller length-at-age. The authors suggest this may be due to local changes in conditions during fish's stay in the sea, although there is limited environmental data to confirm the causal effect. Another question is why there are fewer of these older fish. The authors point to possible increased mortality from disease and/or overfishing. These results may suggest that the situation may be getting worse, as another study finding was that “the more growth seasons an individual spent at sea, the greater was its length-at-first return.” The consequences may be the loss of the oldest and largest individuals, whose disproportionately high reproductive contribution to the population is only now understood (Barneche et al. 2018, Marshall and White 2019). Audzijonyte, A. et al. 2013. Ecological consequences of body size decline in harvested fish species: positive feedback loops in trophic interactions amplify human impact. Biol Lett 9, 20121103. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2012.1103 Oke, K. B. et al. 2020. Recent declines in salmon body size impact ecosystems and fisheries. Nature Communications, 11, 4155. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17726-z Solokas, M. A. et al. 2023. Shrinking body size and climate warming: many freshwater salmonids do not follow the rule. Global Change Biology, 29, 2478-2492. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16626 | Changes in length-at-first return of a sea trout (*Salmo trutta*) population in northern France | Quentin Josset, Laurent Beaulaton, Atso Romakkaniemi, Marie Nevoux | <p style="text-align: justify;">The resilience of sea trout populations is increasingly concerning, with evidence of major demographic changes in some populations. Based on trapping data and related scale collection, we analysed long-term changes ... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Marine ecology | Aleksandra Walczyńska | 2023-11-23 14:36:39 | View | |

28 Jun 2024

Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity: case study on the arboreal-nesting red kite (Milvus milvus)Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Brady J. Mattsson https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.01.569571Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young: you may count too many or too few...Recommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by Steffen Oppel and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Steffen Oppel and 1 anonymous reviewer

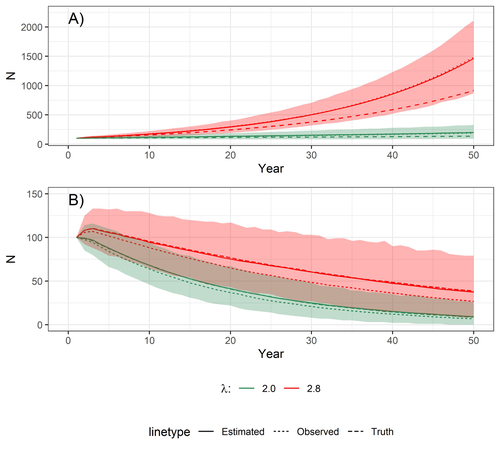

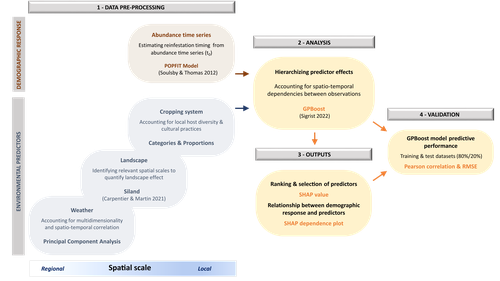

Most species are hard to observe, and different methods are required to estimate demographic parameters such as the number of young individuals produced (one measure of breeding success) and survival. In the former case, and in particular for birds of prey, it often relies upon direct observations of breeding pairs on their nests. Two problems can then occur, that some young are missed and therefore the breeding success is underestimated (“false negatives”), but it is also possible that because for example of the nest structure or vegetation surrounding the nest, more young birds than in fact are present are counted (“false positives”). Sollmann et al. (2024) address this problem by using data where the truth is known as each nest was also accessed after climbing the tree, and a hierarchical model accounting for both undercounts and overcounts. Finally, they assess the impact of this correction on projected population size using simulations. This paper is a solid contribution to the panoply of methods and models that are available for monitoring populations, and has potential applications for many species for which both false positives and false negatives can be a problem. The results on the projected population sizes – showing that for growing populations correcting for bias can lead to large differences in population sizes after a few decades – may seem counterintuitive as population growth rate of long-lived species such as birds of prey is not very sensitive to a change in breeding success (as compared to adult survival). However, one should just be reminded that a small difference in population growth rate may translate to a large difference after many years – for example a growth rate of 1.05 after 50 years mean than population size is multiplied by 11.5, whereas a growth of 1.03 after 50 years mean a multiplication by 4.4, more than twice less individuals. Small differences may matter a lot if they are sustained, and a key aspect of management is to ensure that they are. Of course, management actions having an impact on survival may be more effective, but they might be harder to achieve than for example ensuring that birds of prey breed successfully. References Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Mattsson Brady J. 2024. Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity. bioRxiv, v. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.01.569571

| Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity: case study on the arboreal-nesting red kite (*Milvus milvus*) | Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Brady J. Mattsson | <p style="text-align: justify;">Counting the number of young in a brood from a distance is common practice, for example in tree-nesting birds. These counts can, however, suffer from over and undercounting, which can lead to biased estimates of fec... |  | Demography, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2023-12-11 08:52:22 | View | |

14 Jun 2024

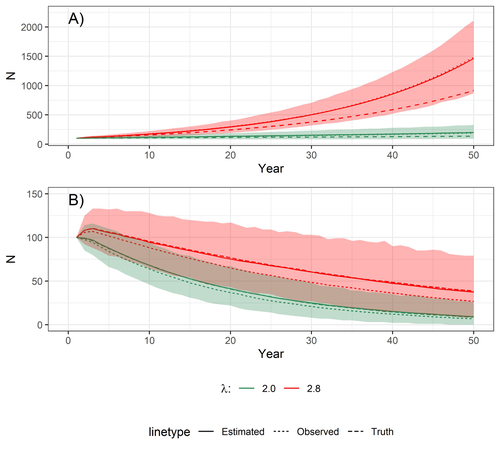

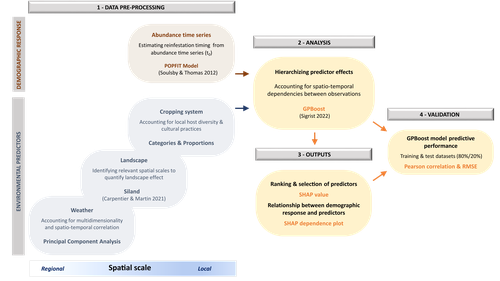

Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of Bactrocera dorsalis population growth in Senegalese orchardsCécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.10.566583Uncovering the ecology in big-data by hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effectsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by Kévin Tougeron and Jianqiang SunAlong with the generalization of open-access practices, large, heterogeneous datasets are becoming increasingly available to ecologists (Farley et al. 2018). While such data offer exciting opportunities for unveiling original patterns and trends, they also raise new challenges regarding how to extract relevant information and actually improve our knowledge of complex ecological systems, beyond purely descriptive correlations (Dietze 2017, Farley et al. 2018). In this work, Caumette et al. (2024) develop an original ecoinformatics approach to relate multi-scale environmental factors to the temporal dynamics of a major pest in mango orchards. Their method relies on the recent tree-boosting method GPBoost (Sigrist 2022) to hierarchize the influence of environmental factors of heterogeneous nature (e.g., orchard composition and management; landscape structure; climate) on the emergence date of the oriental fruit fly, Bactrocera dorsalis. As boosting methods allows the analysis of high-dimensional data, they are particularly adapted to the exploration of such datasets, to uncover unexpected, potentially complex dependencies between ecological dynamics and multiple environmental factors (Farley et al. 2018). In this article, Caumette et al. (2024) make a special effort to guide the reader step by step through their complex analysis pipeline to make it broadly understandable to the average ecologist, which is no small feat. I particularly welcome this commitment, as making new, cutting-edge analytical methods accessible to a large community of science practitioners with varying degrees of statistical or programming expertise is a major challenge for the future of quantitative ecology. The main result of Caumette et al. (2024) is that temperature and humidity conditions both at the local and regional scales are the main predictors of B. dorsalis emergence date, while orchard management practices seem to have relatively little influence. This suggests that favourable climatic conditions may allow the persistence of small populations of B. dorsalis over the dry season, which may then act as a propagule source for early re-infestations. However, as the authors explain, the resulting regression model is not designed for predictive purposes and should not at this stage be used for decision-making in pest management. Its main interest rather resides in identifying potential key factors favoring early infestations of B. dorsalis, and help focusing future experimental field studies on the most relevant levers for integrated pest management in mango orchards. In a wider perspective, this work also provides a convincing proof-of-concept for the use of boosting methods to identify the most influential factors in large, multivariate datasets in a variety of ecological systems. It is also crucial to keep in mind that the current exponential growth in high-throughput environmental data (Lucivero 2020) could quickly come into conflict with the need to reduce the environmental footprint of research (Mariette et al. 2022). In this context, robust and accessible methods for extracting and exploiting all the information available in already existing datasets might prove essential to a sustainable pursuit of science. References Dietze MC. 2017. Ecological Forecasting. Princeton University Press Mariette J, Blanchard O, Berné O, Aumont O, Carrey J, Ligozat A-L, Lellouch E, Roche P-E, Guennebaud G, Thanwerdas J, Bardou P, Salin G, Maigne E, Servan S, Ben-Ari T 2022. An open-source tool to assess the carbon footprint of research. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2022. https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2634-4505/ac84a4 | Hierarchizing multi-scale environmental effects on agricultural pest population dynamics: a case study on the annual onset of *Bactrocera dorsalis* population growth in Senegalese orchards | Cécile Caumette, Paterne Diatta, Sylvain Piry, Marie-Pierre Chapuis, Emile Faye, Fabio Sigrist, Olivier Martin, Julien Papaïx, Thierry Brévault, Karine Berthier | <p>Implementing integrated pest management programs to limit agricultural pest damage requires an understanding of the interactions between the environmental variability and population demographic processes. However, identifying key environmental ... |  | Demography, Landscape ecology, Statistical ecology | Elodie Vercken | 2023-12-11 17:02:08 | View | |

24 May 2024

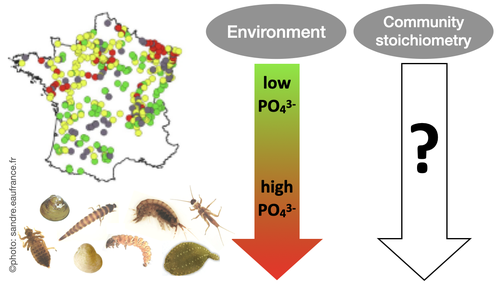

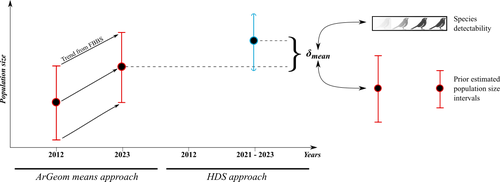

Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale studyMiriam Beck, Elise Billoir, Philippe Usseglio-Polatera, Albin Meyer, Edwige Gautreau, Michael Danger https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.01.574823The influence of water phosphorus and nitrogen loads on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometryRecommended by Huihuang Chen based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo and 1 anonymous reviewer

The manuscript by Beck et al. (2024) investigates the effects of water phosphorus and nitrogen loads on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry across France. Utilizing data from over 1300 standardized sampling events, this research finds that community stoichiometry is significantly influenced by water phosphorus concentration, with the strongest effects at low nitrogen levels. The results demonstrate that the assumptions of Ecological Stoichiometry Theory apply at the community level for at least two dominant taxa and across a broad spatial scale, with probable implications for nutrient cycling and ecosystem functionality. This manuscript contributes to ecological theory, particularly by extending Ecological Stoichiometry Theory to include community-level interactions, clarifying the impact of nutrient concentrations on community structure and function, and informing nutrient management and conservation strategies. In summary, this study not only addresses a gap in community-level stoichiometric research but also delivers crucial empirical support for advancing ecological science and promoting environmental stewardship. References Beck M, Billoir E, Usseglio-Polatera P, Meyer A, Gautreau E and Danger M (2024) Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale study. bioRxiv, 2024.02.01.574823, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.01.574823 | Effects of water nutrient concentrations on stream macroinvertebrate community stoichiometry: a large-scale study | Miriam Beck, Elise Billoir, Philippe Usseglio-Polatera, Albin Meyer, Edwige Gautreau, Michael Danger | <p>Basal resources generally mirror environmental nutrient concentrations in the elemental composition of their tissue, meaning that nutrient alterations can directly reach consumer level. An increased nutrient content (e.g. phosphorus) in primary... |  | Community ecology, Ecological stoichiometry | Huihuang Chen | Thomas Guillemaud, Jun Zuo, Anonymous | 2024-02-02 10:14:01 | View |

29 Jun 2024

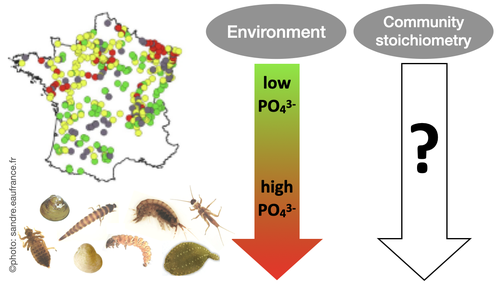

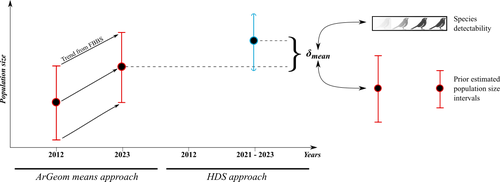

Reassessment of French breeding bird population sizes using citizen science and accounting for species detectabilityJean Nabias, Luc Barbaro, Benoit Fontaine, Jérémy Dupuy, Laurent Couzi, Clément Vallé, Romain Lorrillière https://hal.science/hal-04478371Reassessment of French breeding bird population sizes: from citizen science observations to nationwide estimatesRecommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Estimating populations size of widespread, common species in a relatively large and heterogeneous country like France is difficult for several reasons, from having a sample covering well the diverse ecological gradients to accounting for detectability, the fact that absence of a species may represent a false negative, the species being present but not detected. Bird communities have been the focus of a very large number of studies, with some countries like the UK having long traditions of monitoring both common and rare species. Nabias et al. use a large, structured citizen science project to provide new estimates of common bird species, accounting for detectability and using different habitat and climate covariates to extrapolate abundance to non-sampled areas. About 2/3 of the species had estimates higher than what would have been expected using a previous attempt at estimating population size based in part on expert knowledge and projected using estimates of trends to the period covered by the citizen science sampling. Some species showed large differences between the two estimates, which could be in part explained by accounting for detectability. This paper uses what is called model-based inference (as opposed to design-based inference, that uses the design to make inferences about the whole population; Buckland et al. 2000), both in terms of detectability and habitat suitability. The estimates obtained depend on how well the model components approximate the underlying processes, which in a complex dataset like this one is not easy to assess. But it clearly shows that detectability may have substantial implications for the population size estimates. This is of course not new but has rarely been done at this scale and using a large sample obtained on many species. Interesting further work could focus on testing the robustness of the model-based approach by for example sampling new plots and compare the expected values to the observed values. Such a sampling could be stratified to maximize the discrimination between expected low and high abundances, at least for species where the estimates might be considered as uncertain, or for which estimating population sizes is deemed important. References Buckland, S. T., Goudie, I. B. J., & Borchers, D. L. (2000). Wildlife Population Assessment: Past Developments and Future Directions. Biometrics, 56(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00001.x Nabias, J., Barbaro, L., Fontaine, B., Dupuy, J., Couzi, L., et al. (2024) Reassessment of French breeding bird population sizes using citizen science and accounting for species detectability. HAL, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.science/hal-04478371 | Reassessment of French breeding bird population sizes using citizen science and accounting for species detectability | Jean Nabias, Luc Barbaro, Benoit Fontaine, Jérémy Dupuy, Laurent Couzi, Clément Vallé, Romain Lorrillière | <p style="text-align: justify;">Higher efficiency in large-scale and long-term biodiversity monitoring can be obtained through the use of Essential Biodiversity Variables, among which species population sizes provide key data for conservation prog... |  | Biogeography, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2024-02-26 18:10:27 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle