Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

11 Aug 2023

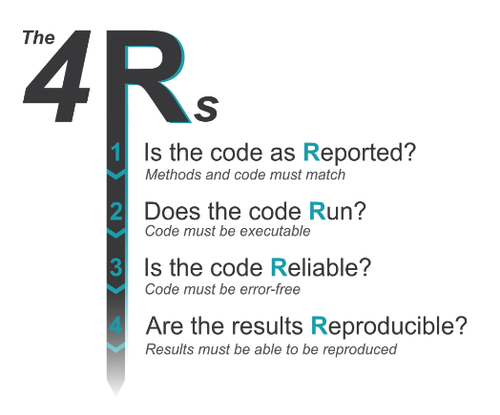

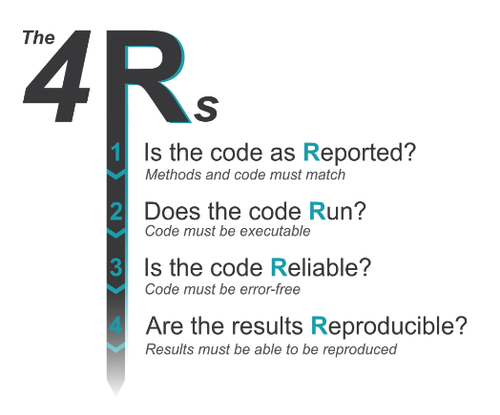

Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary BiologyEdward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64A handy “How to” review code for ecologists and evolutionary biologistsRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewer

Ivimey Cook et al. (2023) provide a concise and useful “How to” review code for researchers in the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology, where the systematic review of code is not yet standard practice during the peer review of articles. Consequently, this article is full of tips for authors on how to make their code easier to review. This handy article applies not only to ecology and evolutionary biology, but to many fields that are learning how to make code more reproducible and shareable. Taking this step toward transparency is key to improving research rigor (Brito et al. 2020) and is a necessary step in helping make research trustable by the public (Rosman et al. 2022). References Brito, J. J., Li, J., Moore, J. H., Greene, C. S., Nogoy, N. A., Garmire, L. X., & Mangul, S. (2020). Recommendations to enhance rigor and reproducibility in biomedical research. GigaScience, 9(6), giaa056. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa056 Ivimey-Cook, E. R., Pick, J. L., Bairos-Novak, K., Culina, A., Gould, E., Grainger, M., Marshall, B., Moreau, D., Paquet, M., Royauté, R., Sanchez-Tojar, A., Silva, I., Windecker, S. (2023). Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. EcoEvoRxiv, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64 Rosman, T., Bosnjak, M., Silber, H., Koßmann, J., & Heycke, T. (2022). Open science and public trust in science: Results from two studies. Public Understanding of Science, 31(8), 1046-1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221100686 | Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Edward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker | <p>Code review increases reliability and improves reproducibility of research. As such, code review is an inevitable step in software development and is common in fields such as computer science. However, despite its importance, code review is not... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology | Corina Logan | 2023-05-19 15:54:01 | View | |

19 Aug 2020

Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metricsF. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux https://doi.org/10.1101/640995Good practice guidelines for testing species-isolation relationships in patch-matrix systemsRecommended by Damaris Zurell based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersConservation biology is strongly rooted in the theory of island biogeography (TIB). In island systems where the ocean constitutes the inhospitable matrix, TIB predicts that species richness increases with island size as extinction rates decrease with island area (the species-area relationship, SAR), and species richness increases with connectivity as colonisation rates decrease with island isolation (the species-isolation relationship, SIR)[1]. In conservation biology, patches of habitat (habitat islands) are often regarded as analogous to islands within an unsuitable matrix [2], and SAR and SIR concepts have received much attention as habitat loss and habitat fragmentation are increasingly threatening biodiversity [3,4]. References [1] MacArthur, R.H. and Wilson, E.O. (1967) The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton. | Three points of consideration before testing the effect of patch connectivity on local species richness: patch delineation, scaling and variability of metrics | F. Laroche, M. Balbi, T. Grébert, F. Jabot & F. Archaux | <p>The Theory of Island Biogeography (TIB) promoted the idea that species richness within sites depends on site connectivity, i.e. its connection with surrounding potential sources of immigrants. TIB has been extended to a wide array of fragmented... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Damaris Zurell | 2019-05-20 16:03:47 | View | |

22 Apr 2021

The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populationsVercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868Allee effects under the magnifying glassRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Tom Van Dooren, Dani Oro and 1 anonymous reviewer

For decades, the effect of population density on individual performance has been studied by ecologists using both theoretical, observational, and experimental approaches. The generally accepted definition of the Allee effect is a positive correlation between population density and average individual fitness that occurs at low population densities, while individual fitness is typically decreased through intraspecific competition for resources at high population densities. Allee effects are very relevant in conservation biology because species at low population densities would then be subjected to much higher extinction risks. However, due to all kinds of stochasticity, low population numbers are always more vulnerable to extinction than larger population sizes. This effect by itself cannot be necessarily ascribed to lower individual performance at low densities, i.e, Allee effects. Vercken and colleagues (2021) address this challenging question and measure the extent to which average individual fitness is affected by population density analyzing 30 experimental populations. As a model system, they use populations of parasitoid wasps of the genus Trichogramma. They report Allee effect in 8 out 30 experimental populations. Vercken and colleagues's work has several strengths. First of all, it is nice to see that they put theory at work. This is a very productive way of using theory in ecology. As a starting point, they look at what simple theoretical population models say about Allee effects (Lewis and Kareiva 1993; Amarasekare 1998; Boukal and Berec 2002). These models invariably predict a one-humped relation between population-density and per-capita growth rate. It is important to remark that pure logistic growth, the paradigm of density-dependence, would never predict such qualitative behavior. It is only when there is a depression of per-capita growth rates at low densities that true Allee effects arise. Second, these authors manage to not only experimentally test this main prediction but also report additional demographic traits that are consistently affected by population density. In these wasps, individual performance can be measured in terms of the average number of individuals every adult is able to put into the next generation ---the lambda parameter in their analysis. The first panel in figure 3 shows that the per-capita growth rates are lower in populations presenting Allee effects, the ones showing a one-humped behavior in the relation between per-capita growth rates and population densities (see figure 2). Also other population traits, such maximum population size and exitinction probability, change in a correlated and consistent manner. In sum, Vercken and colleagues's results are experimentally solid and based on theory expectations. However, they are very intriguing. They find the signature of Allee effects in only 8 out 30 populations, all from the same genus Trichogramma, and some populations belonging to the same species (from different sampling sites) do not show consistently Allee effects. Where does this population variability comes from? What are the reasons underlying this within- and between-species variability? What are the individual mechanisms driving Allee effects in these populations? Good enough, this piece of work generates more intriguing questions than the question is able to clearly answer. Science is not a collection of final answers but instead good questions are the ones that make science progress. References Amarasekare P (1998) Allee Effects in Metapopulation Dynamics. The American Naturalist, 152, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1086/286169 Boukal DS, Berec L (2002) Single-species Models of the Allee Effect: Extinction Boundaries, Sex Ratios and Mate Encounters. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 218, 375–394. https://doi.org/10.1006/jtbi.2002.3084 Lewis MA, Kareiva P (1993) Allee Dynamics and the Spread of Invading Organisms. Theoretical Population Biology, 43, 141–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/tpbi.1993.1007 Vercken E, Groussier G, Lamy L, Mailleret L (2021) The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations. HAL, hal-02570868, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02570868 | The hidden side of the Allee effect: correlated demographic traits and extinction risk in experimental populations | Vercken Elodie, Groussier Géraldine, Lamy Laurent, Mailleret Ludovic | <p style="text-align: justify;">Because Allee effects (i.e., the presence of positive density-dependence at low population size or density) have major impacts on the dynamics of small populations, they are routinely included in demographic models ... |  | Demography, Experimental ecology, Population ecology | David Alonso | 2020-09-30 16:38:29 | View | |

12 Sep 2023

Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patternsYuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913The impact of process at different scales on diversity and ecosystem functioning: a huge challengeRecommended by David Alonso based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Shai Pilosof, Gian Marco Palamara and 1 anonymous reviewer

Scale is a big topic in ecology [1]. Environmental variation happens at particular scales. The typical scale at which organisms disperse is species-specific, but, as a first approximation, an ensemble of similar species, for instance, trees, could be considered to share a typical dispersal scale. Finally, characteristic spatial scales of species interactions are, in general, different from the typical scales of dispersal and environmental variation. Therefore, conceptually, we can distinguish these three characteristic spatial scales associated with three different processes: species selection for a given environment (E), dispersal (D), and species interactions (I), respectively. From the famous species-area relation to the spatial distribution of biomass and species richness, the different macro-ecological patterns we usually study emerge from an interplay between dispersal and local interactions in a physical environment that constrains species establishment and persistence in every location. To make things even more complicated, local environments are often modified by the species that thrive in them, which establishes feedback loops. It is usually assumed that local interactions are short-range in comparison with species dispersal, and dispersal scales are typically smaller than the scales at which the environment varies (I < D < E, see [2]), but this should not always be the case. The authors of this paper [2] relax this typical assumption and develop a theoretical framework to study how diversity and ecosystem functioning are affected by different relations between the typical scales governing interactions, dispersal, and environmental variation. This is a huge challenge. First, diversity and ecosystem functioning across space and time have been empirically characterized through a wide variety of macro-ecological patterns. Second, accommodating local interactions, dispersal and environmental variation and species environmental preferences to model spatiotemporal dynamics of full ecological communities can be done also in a lot of different ways. One can ask if the particular approach suggested by the authors is the best choice in the sense of producing robust results, this is, results that would be predicted by alternative modeling approaches and mathematical analyses [3]. The recommendation here is to read through and judge by yourself. The main unusual assumption underlying the model suggested by the authors is non-local species interactions. They introduce interaction kernels to weigh the strength of the ecological interaction with distance, which gives rise to a system of coupled integro-differential equations. This kernel is the key component that allows for control and varies the scale of ecological interactions. Although this is not new in ecology [4], and certainly has a long tradition in physics ---think about the electric or the gravity field, this approach has been widely overlooked in the development of the set of theoretical frameworks we have been using over and over again in community ecology, such as the Lotka-Volterra equations or, more recently, the metacommunity concept [5]. In Physics, classic fields have been revised to account for the fact that information cannot travel faster than light. In an analogous way, a focal individual cannot feel the presence of distant neighbors instantaneously. Therefore, non-local interactions do not exist in ecological communities. As the authors of this paper point out, they emerge in an effective way as a result of non-random movements, for instance, when individuals go regularly back and forth between environments (see [6], for an application to infectious diseases), or even migrate between regions. And, on top of this type of movement, species also tend to disperse and colonize close (or far) environments. Individual mobility and dispersal are then two types of movements, characterized by different spatial-temporal scales in general. Species dispersal, on the one hand, and individual directed movements underlying species interactions, on the other, are themselves diverse across species, but it is clear that they exist and belong to two distinct categories. In spite of the long and rich exchange between the authors' team and the reviewers, it was not finally clear (at least, to me and to one of the reviewers) whether the model for the spatio-temporal dynamics of the ecological community (see Eq (1) in [2]) is only presented as a coupled system of integro-differential equations on a continuous landscape for pedagogical reasons, but then modeled on a discrete regular grid for computational convenience. In the latter case, the system represents a regular network of local communities, becomes a system of coupled ODEs, and can be numerically integrated through the use of standard algorithms. By contrast, in the former case, the system is meant to truly represent a community that develops on continuous time and space, as in reaction-diffusion systems. In that case, one should keep in mind that numerical instabilities can arise as an artifact when integrating both local and non-local spatio-temporal systems. Spatial patterns could be then transient or simply result from these instabilities. Therefore, when analyzing spatiotemporal integro-differential equations, special attention should be paid to the use of the right numerical algorithms. The authors share all their code at https://zenodo.org/record/5543191, and all this can be checked out. In any case, the whole discussion between the authors and the reviewers has inherent value in itself, because it touches on several limitations and/or strengths of the author's approach, and I highly recommend checking it out and reading it through. Beyond these methodological issues, extensive model explorations for the different parameter combinations are presented. Several results are reported, but, in practice, what is then the main conclusion we could highlight here among all of them? The authors suggest that "it will be difficult to manage landscapes to preserve biodiversity and ecosystem functioning simultaneously, despite their causative relationship", because, first, "increasing dispersal and interaction scales had opposing References [1] Levin, S. A. 1992. The problem of pattern and scale in ecology. Ecology 73:1943–1967. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941447 [2] Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain. 2023. Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.11.463913 [3] Baron, J. W. and Galla, T. 2020. Dispersal-induced instability in complex ecosystems. Nature Communications 11, 6032. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19824-4 [4] Cushing, J. M. 1977. Integrodifferential equations and delay models in population dynamics [5] M. A. Leibold, M. Holyoak, N. Mouquet, P. Amarasekare, J. M. Chase, M. F. Hoopes, R. D. Holt, J. B. Shurin, R. Law, D. Tilman, M. Loreau, A. Gonzalez. 2004. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters, 7(7): 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x [6] M. Pardo-Araujo, D. García-García, D. Alonso, and F. Bartumeus. 2023. Epidemic thresholds and human mobility. Scientific reports 13 (1), 11409. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38395-0 | Linking intrinsic scales of ecological processes to characteristic scales of biodiversity and functioning patterns | Yuval R. Zelnik, Matthieu Barbier, David W. Shanafelt, Michel Loreau, Rachel M. Germain | <p style="text-align: justify;">Ecology is a science of scale, which guides our description of both ecological processes and patterns, but we lack a systematic understanding of how process scale and pattern scale are connected. Recent calls for a ... | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Dispersal & Migration, Ecosystem functioning, Landscape ecology, Theoretical ecology | David Alonso | 2021-10-13 23:24:45 | View | ||

20 Jun 2019

Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predatorChristophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel https://doi.org/10.1101/472431Sexual segregation in a sexually dimorphic seabird: a matter of spatial scaleRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by Dries Bonte and 1 anonymous reviewerSexual segregation appears in many taxa and can have important ecological, evolutionary and conservation implications. Sexual segregation can take two forms: either the two sexes specialise in different habitats but share the same area (habitat segregation), or they occupy the same habitat but form separate, unisex groups (social segregation) [1,2]. Segregation would have evolved as a way to avoid, or at least, reduce intersexual competition. References [1] Conradt, L. (2005). Definitions, hypotheses, models and measures in the study of animal segregation. In Sexual segregation in vertebrates: ecology of the two sexes (Ruckstuhl K.E. and Neuhaus, P. eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Pp:11–34. | Sexual segregation in a highly pagophilic and sexually dimorphic marine predator | Christophe Barbraud, Karine Delord, Akiko Kato, Paco Bustamante, Yves Cherel | <p>Sexual segregation is common in many species and has been attributed to intra-specific competition, sex-specific differences in foraging efficiency or in activity budgets and habitat choice. However, very few studies have simultaneously quantif... |  | Foraging, Marine ecology | Denis Réale | Dries Bonte, Anonymous | 2018-11-19 13:40:59 | View |

08 Aug 2020

Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predatorChris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips https://doi.org/10.1101/856997While the quoll’s away, the mice will play… and the seeds will payRecommended by Denis Réale based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersA predator can strongly influence the demography of its prey, which can have profound carryover effects on the trophic network; so-called density-mediated indirect interactions (DMII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006). Furthermore, a novel predator can alter the phenotypes of its prey for traits that will change prey foraging efficiency. These trait-mediated indirect interactions may in turn have cascading effects on the demography and features of the basal resources consumed by the intermediate consumer (TMIII; Werner and Peacor 2003; Schmitz et al. 2004; Trussell et al. 2006), but very few studies have looked for these effects (Trusell et al. 2006). The study “Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator”, by Jolly et al. (2020) is therefore a much-needed addition to knowledge in this field. The authors have profited from a rare introduction of Northern quolls (Dasyurus hallucatus) on an Australian island, to examine both the density-mediated and trait-mediated indirect interactions with grassland melomys (Melomys burtoni) and the vegetation of their woodland habitat. References -Bell G, Gonzalez A (2009) Evolutionary rescue can prevent extinction following environmental change. Ecology letters, 12(9), 942-948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01350.x | Trophic cascade driven by behavioural fine-tuning as naïve prey rapidly adjust to a novel predator | Chris J Jolly, Adam S Smart, John Moreen, Jonathan K Webb, Graeme R Gillespie and Ben L Phillips | <p>The arrival of novel predators can trigger trophic cascades driven by shifts in prey numbers. Predators also elicit behavioural change in prey populations, via phenotypic plasticity and/or rapid evolution, and such changes may also contribute t... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Foraging, Herbivory, Population ecology, Terrestrial ecology, Tropical ecology | Denis Réale | 2019-11-27 21:39:44 | View | |

02 Jun 2021

Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populationsOlivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.28.428563Blue tits surviving in an ever-changing worldRecommended by Dieter Lukas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas based on reviews by Ana Sanz-Aguilar and Vicente García-Navas

How long individuals live has a large influence on a number of biological processes, both for the individuals themselves as well as for the populations they live in. For a given species, survival is often summarized in curves showing the probability to survive from one age to the next. However, these curves often hide a large amount of variation in survival. Variation can occur from chance, or if individuals have different genotypes or phenotypes that can influence how long they might live, or if environmental conditions are not the same across time or space. Such spatiotemporal variations in the conditions that individuals experience can lead to complex patterns of evolution (Kokko et al. 2017) but because of the difficulties to obtain the relevant data they have not been studied much in natural populations. Charmantier A, Doutrelant C, Dubuc-Messier G, Fargevieille A, Szulkin M (2016) Mediterranean blue tits as a case study of local adaptation. Evolutionary Applications, 9, 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.12282 Dubuc-Messier G, Réale D, Perret P, Charmantier A (2017) Environmental heterogeneity and population differences in blue tits personality traits. Behavioral Ecology, 28, 448–459. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arw148 Kokko H, Chaturvedi A, Croll D, Fischer MC, Guillaume F, Karrenberg S, Kerr B, Rolshausen G, Stapley J (2017) Can Evolution Supply What Ecology Demands? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.12.005 Lewontin RC, Cohen D (1969) On Population Growth in a Randomly Varying Environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 62, 1056–1060. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.62.4.1056 | Identifying drivers of spatio-temporal variation in survival in four blue tit populations | Olivier Bastianelli, Alexandre Robert, Claire Doutrelant, Christophe de Franceschi, Pablo Giovannini, Anne Charmantier | <p style="text-align: justify;">In a context of rapid climate change, the influence of large-scale and local climate on population demography is increasingly scrutinized, yet studies are usually focused on one population. Demographic parameters, i... |  | Climate change, Demography, Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Population ecology | Dieter Lukas | 2021-01-29 15:24:23 | View | |

25 Oct 2021

The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakesNicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner https://doi.org/10.1101/373332The difficult interpretation of species co-distributionRecommended by Dominique Gravel based on reviews by Anthony Maire and Emilie MackeEcology is the study of the distribution of organisms in space and time and their interactions. As such, there is a tradition of studies relating abiotic environmental conditions to species distribution, while another one is concerned by the effects of consumers on the abundance of their resources. Interestingly, joining the dots appears more difficult than it would suggest: eluding the effect of species interactions on distribution remains one of the greatest challenges to elucidate nowadays (Kissling et al. 2012). Theory suggests that yes, species interactions such as predation and competition should influence range limits (Godsoe et al. 2017), but the common intuition among many biogeographers remains that over large areas such as regions and continents, environmental drivers like temperature and precipitation overwhelm their local effects. Answering this question is of primary importance in the context where species are moving around with climate warming. Inconsistencies in food web structure may arise with asynchronized movements of consumers and their resources, leading to a major disruption in regulation and potentially ecosystem functioning. Solving this problem, however, remains very challenging because we have to rely on observational data since experiments are hard to perform at the biogeographical scale. The study of St-Gelais is an interesting step forward to solve this problem. Their main objective was to assess the strength of the association between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities at a large spatial scale, looking at the spatial covariation of both taxonomic and functional composition. To do so, they undertook a massive survey of more than 100 lakes across three regions of the boreal region of Québec. Species and functional composition were recorded, along with a set of abiotic variables. Classic community ecology at this point. The difficulty they faced was to disentangle the multiple causal relationships involved in the distribution of both trophic levels. Teasing apart bottom-up and top-down forces driving the assembly of plankton communities using observational data is not an easy task. On the one hand, both trophic levels could respond to variations in temperature, nutrient availability and dissolved organic carbon. The interpretation is fairly straightforward if the two levels respond to different factors, but the situation is much more complicated when they do respond similarly. There are potentially three possible underlying scenarios. First, the phyto and zooplankton communities may share the same environmental requirements, thereby generating a joint distribution over gradients such as temperature and nutrient availability. Second, the abiotic environment could drive the distribution of the phytoplankton community, which would then propagate up and influence the distribution of the zooplankton community. Alternatively, the abiotic environment could constrain the distribution of the zooplankton, which could then affect the one of phytoplankton. In addition to all of these factors, St-Gelais et al also consider that dispersal may limit the distribution, well aware of previous studies documenting stronger dispersal limitations for zooplankton communities. Unfortunately, there is not a single statistical approach that could be taken from the shelf and used to elucidate drivers of co-distribution. Joint species distribution was once envisioned as a major step forward in this direction (Warton et al. 2015), but there are several limits preventing the direct interpretation that co-occurrence is linked to interactions (Blanchet et al. 2020). Rather, St-Gelais used a variety of multivariate statistics to reveal the structure in their observational data. First, using a Procrustes analysis (a method testing if the spatial variation of one community is correlated to the structure of another community), they found a significant correlation between phytoplankton and zooplankton communities, indicating a taxonomic coupling between the groups. Interestingly, this observation was maintained for functional composition only when interaction-related traits were considered. At this point, these results strongly suggest that interactions are involved in the correlation, but it's hard to decipher between bottom-up and top-down perspectives. A complementary analysis performed with a constrained ordination, per trophic level, provided complementary pieces of information. First observation was that only functional variation was found to be related to the different environmental variables, not taxonomic variation. Despite that trophic levels responded to water quality variables, spatial autocorrelation was more important for zooplankton communities and the two layers appear to respond to different variables. It is impossible with those results to formulate a strong conclusion about whether grazing influence the co-distribution of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities. That's the mere nature of observational data. While there is a strong spatial association between them, there are also diverging responses to the different environmental variables considered. But the contrast between taxonomic and functional composition is nonetheless informative and it seems that beyond the idiosyncrasies of species composition, trait distribution may be more informative and general. Perhaps the most original contribution of this study is the hierarchical approach to analyze the data, combined with the simultaneous analysis of taxonomic and functional distributions. Having access to a vast catalog of multivariate statistical techniques, a careful selection of analyses helps revealing key features in the data, rejecting some hypotheses and accepting others. Hopefully, we will see more and more of such multi-trophic approaches to distribution because it is now clear that the factors driving distribution are much more complicated than anticipated in more traditional analyses of community data. Biodiversity is more than a species list, it is also all of the interactions between them, influencing their distribution and abundance (Jordano 2016). References Blanchet FG, Cazelles K, Gravel D (2020) Co-occurrence is not evidence of ecological interactions. Ecology Letters, 23, 1050–1063. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13525 Godsoe W, Jankowski J, Holt RD, Gravel D (2017) Integrating Biogeography with Contemporary Niche Theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 32, 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.03.008 Jordano P (2016) Chasing Ecological Interactions. PLOS Biology, 14, e1002559. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002559 Kissling WD, Dormann CF, Groeneveld J, Hickler T, Kühn I, McInerny GJ, Montoya JM, Römermann C, Schiffers K, Schurr FM, Singer A, Svenning J-C, Zimmermann NE, O’Hara RB (2012) Towards novel approaches to modelling biotic interactions in multispecies assemblages at large spatial extents. Journal of Biogeography, 39, 2163–2178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02663.x St-Gelais NF, Vogt RJ, Giorgio PA del, Beisner BE (2021) The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes. bioRxiv, 373332, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/373332 Warton DI, Blanchet FG, O’Hara RB, Ovaskainen O, Taskinen S, Walker SC, Hui FKC (2015) So Many Variables: Joint Modeling in Community Ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 30, 766–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.007 Wisz MS, Pottier J, Kissling WD, Pellissier L, Lenoir J, Damgaard CF, Dormann CF, Forchhammer MC, Grytnes J-A, Guisan A, Heikkinen RK, Høye TT, Kühn I, Luoto M, Maiorano L, Nilsson M-C, Normand S, Öckinger E, Schmidt NM, Termansen M, Timmermann A, Wardle DA, Aastrup P, Svenning J-C (2013) The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biological Reviews, 88, 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x | The taxonomic and functional biogeographies of phytoplankton and zooplankton communities across boreal lakes | Nicolas F St-Gelais, Richard J Vogt, Paul A del Giorgio, Beatrix E Beisner | <p>Strong trophic interactions link primary producers (phytoplankton) and consumers (zooplankton) in lakes. However, the influence of such interactions on the biogeographical distribution of the taxa and functional traits of planktonic organ... |  | Biogeography, Community ecology, Species distributions | Dominique Gravel | 2018-07-24 15:01:51 | View | |

18 Apr 2024

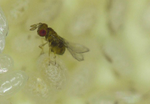

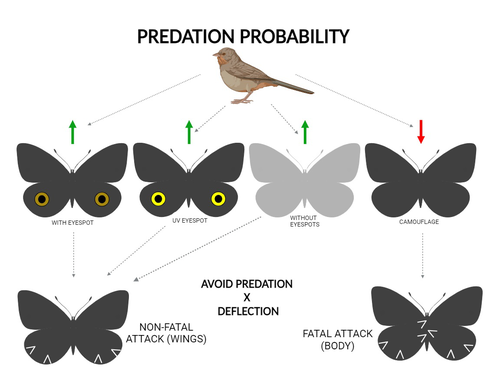

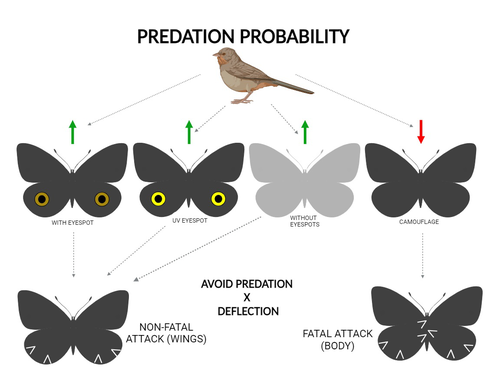

The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in natureCristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357Intimidation or deflection: field experiments in a tropical forest to simultaneously test two competing hypotheses about how butterfly eyespots confer protection against predatorsRecommended by Doyle Mc Key based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Eyespots—round or oval spots, usually accompanied by one or more concentric rings, that together imitate vertebrate eyes—are found in insects of at least three orders and in some tropical fishes (Stevens 2005). They are particularly frequent in Lepidoptera, where they occur on wings of adults in many species (Monteiro et al. 2006), and in caterpillars of many others (Janzen et al. 2010). The resemblance of eyespots to vertebrate eyes often extends to details, such as fake « pupils » (round or slit-like) and « eye sparkle » (Blut et al. 2012). Larvae of one hawkmoth species even have fake eyes that appear to blink (Hossie et al. 2013). Eyespots have interested evolutionary biologists for well over a century. While they appear to play a role in mate choice in some adult Lepidoptera, their adaptive significance in adult Lepidoptera, as in caterpillars, is mainly as an anti-predator defense (Monteiro 2015). However, there are two competing hypotheses about the mechanism by which eyespots confer defense against predators. The « intimidation » hypothesis postulates that eyespots intimidate potential predators, startling them and reducing the probability of attack. The « deflection » hypothesis holds that eyespots deflect attacks to parts of the body where attack has relatively little effect on the animal’s functioning and survival. In caterpillars, there is little scope for the deflection hypothesis, because attack on any part of a caterpillar’s body is likely to be lethal. Much observational and some experimental evidence supports the intimidation hypothesis in caterpillars (Hossie & Sherratt 2012). In adult Lepidoptera, however, both mechanisms are plausible, and both have found support (Stevens 2005). The most spectacular examples of intimidation are in butterflies in which eyespots located centrally in hindwings and hidden in the natural resting position are suddenly exposed, startling the potential predator (e.g., Vallin et al. 2005). The most spectacular examples of deflection are seen in butterflies in which eyespots near the hindwing margin combined with other traits give the appearance of a false head (e.g., Chotard et al. 2022; Kodandaramaiah 2011). Most studies have attempted to test for only one or the other of these mechanisms—usually the one that seems a priori more likely for the butterfly species being studied. But for many species, particularly those that have neither spectacular startle displays nor spectacular false heads, evidence for or against the two hypotheses is contradictory. Iserhard et al. (2024) attempted to simultaneously test both hypotheses, using the neotropical nymphalid butterfly Caligo martia. This species has a large ventral hindwing eyespot, exposed in the insect’s natural resting position, while the rest of the ventral hindwing surface is cryptically coloured. In a previous study of this species, De Bona et al. (2015) presented models with intact and disfigured eyespots on a computer monitor to a European bird species, the great tit (Parus major). The results favoured the intimidation hypothesis. Iserhard et al. (2024) devised experiments presenting more natural conditions, using fairly realistic dummy butterflies, with eyespots manipulated or unmanipulated, exposed to a diverse assemblage of insectivorous birds in nature, in a tropical forest. Using color-printed paper facsimiles of wings, with eyespots present, UV-enhanced, or absent, they compared the frequency of beakmarks on modeling clay applied to wing margins (frequent attacks would support the deflection hypothesis) and (in one of two experiments) on dummies with a modeling-clay body (eyespots should lead to reduced frequency of attack, to wings and body, if birds are intimidated). Their experiments also included dummies without eyespots whose wings were either cryptically coloured (as in unmanipulated butterflies) or not. Their results, although complex, indicate support for the deflection hypothesis: dummies with eyespots were mostly attacked on these less vital parts. Dummies lacking eyespots were less frequently attacked, especially when they were camouflaged. Camouflaged dummies without eyespots were in fact the least frequently attacked of all the models. However, when dummies lacking eyespots were attacked, attacks were usually directed to vital body parts. These results show some of the complexity of estimating costs and benefits of protective conspicuous signals vs. camouflage (Stevens et al. 2008). Two complementary experiments were conducted. The first used facsimiles with « wings » in a natural resting position (folded, ventral surfaces exposed), but without a modeling-clay « body ». In the second experiment, facsimiles had a modeling-clay « body », placed between the two unfolded wings to make it as accessible to birds as the wings. However, these dummies displayed the ventral surfaces of unfolded wings, an unnatural resting position. The study was thus not able to compare bird attacks to the body vs. wings in a natural resting position. One can understand the reason for this methodological choice, but it is a limitation of the study. The naturalness of the conditions under which these field experiments were conducted is a strong argument for the biological significance of their results. However, the uncontrolled conditions naturally result in many questions being left open. The butterfly dummies were exposed to at least nine insectivorous bird species. Do bird species differ in their behavioral response to eyespots? Do responses depend on the distance at which a bird first detects the butterfly? Do eyespots and camouflage markings present on the same animal both function, but at different distances (Tullberg et al. 2005)? Do bird responses vary depending on the particular light environment in the places and at the times when they encounter the butterfly (Kodandaramaiah 2011)? Answering these questions under natural, uncontrolled conditions will be challenging, requiring onerous methods, (e.g., video recording in multiple locations over time). The study indicates the interest of pursuing these questions. References Blut, C., Wilbrandt, J., Fels, D., Girgel, E.I., & Lunau, K. (2012). The ‘sparkle’ in fake eyes–the protective effect of mimic eyespots in Lepidoptera. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 143, 231-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2012.01260.x Chotard, A., Ledamoisel, J., Decamps, T., Herrel, A., Chaine, A.S., Llaurens, V., & Debat, V. (2022). Evidence of attack deflection suggests adaptive evolution of wing tails in butterflies. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 289, 20220562. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.0562 De Bona, S., Valkonen, J.K., López-Sepulcre, A., & Mappes, J. (2015). Predator mimicry, not conspicuousness, explains the efficacy of butterfly eyespots. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 282, 1806. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSPB.2015.0202 Hossie, T.J., & Sherratt, T.N. (2012). Eyespots interact with body colour to protect caterpillar-like prey from avian predators. Animal Behaviour, 84, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.027 Hossie, T.J., Sherratt, T.N., Janzen, D.H., & Hallwachs, W. (2013). An eyespot that “blinks”: an open and shut case of eye mimicry in Eumorpha caterpillars (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae). Journal of Natural History, 47, 2915-2926. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2013.791935 Iserhard, C.A., Malta, S.T., Penz, C.M., Brenda Barbon Fraga; Camila Abel da Costa; Taiane Schwantz; & Kauane Maiara Bordin (2024). The large and central Caligo martia eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds : a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature. Zenodo, ver. 1 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10980357 Janzen, D.H., Hallwachs, W., & Burns, J.M. (2010). A tropical horde of counterfeit predator eyes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 107, 11659-11665. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912122107 Kodandaramaiah, U. (2011). The evolutionary significance of butterfly eyespots. Behavioral Ecology, 22, 1264-1271. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr123 Monteiro, A. (2015). Origin, development, and evolution of butterfly eyespots. Annual Review of Entomology, 60, 253-271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020942 Monteiro, A., Glaser, G., Stockslager, S., Glansdorp, N., & Ramos, D. (2006). Comparative insights into questions of lepidopteran wing pattern homology. BMC Developmental Biology, 6, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-213X-6-52 Stevens, M. (2005). The role of eyespots as anti-predator mechanisms, principally demonstrated in the Lepidoptera. Biological Reviews, 80, 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793105006810 Stevens, M., Stubbins, C.L., & Hardman C.J. (2008). The anti-predator function of ‘eyespots’ on camouflaged and conspicuous prey. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62, 1787-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0607-3 Tullberg, B.S., Merilaita, S., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Aposematism and crypsis combined as a result of distance dependence: functional versatility of the colour pattern in the swallowtail butterfly larva. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1315-1321. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3079 Vallin, A., Jakobsson, S., Lind, J., & Wiklund, C. (2005). Prey survival by predator intimidation: an experimental study of peacock butterfly defence against blue tits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 272, 1203-1207. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2004.3034 | The large and central *Caligo martia* eyespot may reduce fatal attacks by birds: a case study supports the deflection hypothesis in nature | Cristiano Agra Iserhard, Shimene Torve Malta, Carla Maria Penz, Brenda Barbon Fraga, Camila Abel da Costa, Taiane Schwantz, Kauane Maiara Bordin | <p>Many animals have colorations that resemble eyes, but the functions of such eyespots are debated. Caligo martia (Godart, 1824) butterflies have large ventral hind wing eyespots, and we aimed to test whether these eyespots act to deflect or to t... |  | Biodiversity, Community ecology, Conservation biology, Life history, Tropical ecology | Doyle Mc Key | 2023-11-21 15:00:20 | View | |

10 Oct 2018

Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence dataSamuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea https://doi.org/10.1101/256586Combining epidemiological models with statistical inference can detect parasite interactionsRecommended by Dustin Brisson based on reviews by Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne and 1 anonymous reviewerThere are several important topics in the study of infectious diseases that have not been well explored due to technical difficulties. One such topic is pursued by Alizon et al. in “Modelling coinfections to detect within-host interactions from genotype combination prevalences” [1]. Both theory and several important examples have demonstrated that interactions among co-infecting strains can have outsized impacts on disease outcomes, transmission dynamics, and epidemiology. Unfortunately, empirical data on pathogen interactions and their outcomes is often correlational making results difficult to decipher. References [1] Alizon, S., Murall, C.L., Saulnier, E., & Sofonea, M.T. (2018). Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data. bioRxiv, 256586, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/256586 | Detecting within-host interactions using genotype combination prevalence data | Samuel Alizon, Carmen Lía Murall, Emma Saulnier, Mircea T Sofonea | <p>Parasite genetic diversity can provide information on disease transmission dynamics but most methods ignore the exact combinations of genotypes in infections. We introduce and validate a new method that combines explicit epidemiological modelli... |  | Eco-immunology & Immunity, Epidemiology, Host-parasite interactions, Statistical ecology | Dustin Brisson | Samuel Díaz Muñoz, Erick Gagne | 2018-02-01 09:23:26 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle