Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

06 Oct 2020

Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range?Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gspaceuse.htmlExplore and move: a key to success in a changing world?Recommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Joe Nocera, Marion Nicolaus and Laure CauchardChanges in the spatial range of many species are one of the major consequences of the profound alteration of environmental conditions due to human activities. Some species expand, sometimes spectacularly during invasions; others decline; some shift. Because these changes result in local biodiversity loss (whether local species go extinct or are replaced by colonizing ones), understanding the factors driving spatial range dynamics appears crucial to predict biodiversity dynamics. Identifying the factors that shape individual movement is a main step towards such understanding. The study described in this preregistration (McCune et al. 2020) falls within this context by testing possible links between individual exploration behaviour and movements related to daily space use in an avian study model currently rapidly expanding, the great-tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus). Movement and exploration: which direction(s) for the link between exploration and dispersal? Evolutionary and conservation perspectives References Badayev, A. V., Martin, T. E and Etges, W. J. 1996. Habitat sampling and habitat selection by female wild turkeys: ecological correlates and reproductive consequences. Auk 113: 636-646. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/4088984 | Does space use behavior relate to exploration in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range? | Kelsey B. McCune, Cody Ross, Melissa Folsom, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus) are rapidly expanding their geographic range (Wehtje 2003). Range expansion could be facilitated by consistent behavioural differences between individuals on the range edge and those in other parts of th... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Blandine Doligez | 2019-09-30 19:27:40 | View | |

15 Nov 2023

The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabirdKarine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439On the road to adulthood: exploring progressive changes in foraging behaviour during post-fledging immaturity using remote trackingRecommended by Blandine Doligez based on reviews by Juliet Lamb and 1 anonymous reviewerIn most vertebrate species, the period of life spanning from departure from the growing site until reaching a more advanced life stage (immature or adult) is critical. During this period, juveniles are often highly vulnerable because they have not reached the morphological, physiological and behavioural maturity levels of adults yet and are therefore at high risk of mortality, e.g. through starvation, depredation or competition (e.g. Marchetti & Price 1989, Wunderle 1991, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016). In line with this, juvenile survival is most often far lower than adult survival (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992). In species with parental care, juveniles have to acquire behavioural independence from their parents and possibly establish their own territory during this period of life. Very often, this is also the period that is least well-known in the life cycle (Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016) because of reduced accessibility to individuals and/or adoption of low conspicuous behaviours. Therefore, our understanding of how juveniles acquire typical adult behaviours and how this progressively increases their survival prospects is still very limited (Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), and questions such as the length of this transition period or the cognitive (e.g. learning, memorization) mechanisms involved remain largely unresolved. This is particularly true regarding the acquisition of independent foraging behaviour (Marchetti & Price 1989). Because direct observations of juvenile behaviours are usually very difficult except in specific situations or at the cost of an enormous effort, the use of remote tracking devices can be particularly appealing in this context (e.g. Ponchon et al. 2013, Kays et al. 2015). Over the past decades, technical advances have allowed the monitoring of not only individuals’ movements at both large and small spatial scales but also their activities and behaviours based on different parameters recording e.g. speed of movement or diving depth (Whitford & Klimley 2019). Device miniaturization has in particular allowed smaller species to be equipped and/or longer periods of time to be monitored (e.g. Naef-Daenzer et al. 2005). This has opened up whole fields of research, and has been particularly used on marine seabirds. In these species, individuals are most often inaccessible when at sea, representing most of the time outside (and even within) the breeding season, and the life cycle of these long-lived species can include an extended immature period (up to many years) during which most of them will remain unseen, until they come back as breeders or pre-breeders (e.g. Wooller et al. 1992, Oro & Martínez-Abraín 2009). Survival has been found to increase gradually with age in these species before reaching high values characteristic of the adult stage. However, the mechanisms underlying this increase are still to be deciphered. The study by Delord et al. (2023) builds upon the hypothesis that juveniles gradually learn foraging techniques and movement strategies, improving their foraging efficiency, as previous data on flight parameters seemed to show in different long-lived bird species. Yet, these previous studies obtained data over a limited period of time, i.e. a few months at best. Whether these data could capture the whole dynamics of the progressive acquisition of foraging and movement skills can only be assessed by measuring behaviour over a longer time period and comparing it to similar data in adults, to account for seasonal variation in relation to both resource availability and energetic demands, e.g. due to molt. The present study (Delord et al. 2023) addresses these questions by taking advantage of longer-lasting recordings of the location and activity of juvenile, immature and adult birds obtained simultaneously to investigate changes over time in juvenile behaviour and thereby provide hints about how young progressively acquire foraging skills. This study is performed on Amsterdam albatrosses, a highly endangered long-lived sea bird, with obvious conservation issues (Thiebot et al. 2015). The results show progressive changes in foraging effort over the first two months after departure from the birth colony, but large differences remain between life stages over a much longer time frame. They also reveal strong variations between sexes and over time in the year. Overall, this study, therefore, confirms the need for very long-term data to be collected in order to address the question of progressive behavioural maturation and associated survival consequences in such species with strongly deferred maturity. Ideally, the same individuals should be monitored over different life stages, from the juvenile period up to adulthood, but this would require further technical development to release the issue of powering duration limitation. As reviewers emphasized in the first review round, one main challenge now remains to ascertain the outcome of the observed behavioural changes in foraging behaviour: we expect them to reflect improvement in foraging skills and thus performance of juveniles over time, but this would need to be tested. Collecting data on foraging efficiency is yet another challenge, that future technical developments may also help overcome. Importantly also, data were available only for individuals that could be caught again because the tracking device had to be retrieved from the bird. Here, a substantial fraction of the loggers (one-fifth) could not be found again (Delord et al. 2023). To what extent the birds for which no data could be obtained are a random sample of the equipped birds would also need to be assessed. The further development of remote tracking techniques allowing data to be downloaded from a long distance should help further exploration of behavioural ontogeny of juveniles while maturing and its survival consequences. Because the maturation process explored here is likely to show very different characteristics (e.g. timing and speed) in smaller / shorter-lived species (see Cox et al. 2014, Naef-Daenzer & Grüebler 2016), the development of miniaturization is also expected to allow further investigation of post-fledging behavioural maturation in a wider range of bird species. Our understanding of this crucial life phase in different types of species should thus continue to progress in the coming years. References Cox W. A., Thompson F. R. III, Cox A. S. & Faaborg J. 2014. Post-fledging survival in passerine birds and the value of post-fledging studies to conservation. Journal of Wildlife Management, 78: 183-193. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.670 Delord K., Weimerskirch H. & Barbraud C. 2023. The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird. bioRxiv, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.23.465439 Kays R., Crofoot M. C., Jetz W. & Wikelski M. 2015. Terrestrial animal tracking as an eye on life and planet. Science, 348 (6240). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa2478 Marchetti K: & Price T. 1989. Differences in the foraging of juvenile and adult birds: the importance of developmental constraints. Biological Reviews, 64: 51-70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1989.tb00638.x Naef-Daenzer B., Fruh D., Stalder M., Wetli P. & Weise E. 2005. Miniaturization (0.2 g) and evaluation of attachment techniques of telemetry transmitters. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 208: 4063–4068. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01870 Naef-Daenzer B. & Grüebler M. U. 2016. Post-fledging survival of altricial birds: ecological determinants and adaptation. Journal of Field Ornithology, 87: 227-250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofo.12157 Oro D. & Martínez-Abraín A. 2009. Ecology and behavior of seabirds. Marine Ecology, pp.364-389. Ponchon A., Grémillet D., Doligez B., Chambert T., Tveera T., Gonzàles-Solìs J & Boulinier T. 2013. Tracking prospecting movements involved in breeding habitat selection: insights, pitfalls and perspectives. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 4: 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2012.00259.x Thiebot J.-B., Delord K., Barbraud C., Marteau C. & Weimerskirch H. 2015. 167 individuals versus millions of hooks: bycatch mitigation in longline fisheries underlies conservation of Amsterdam albatrosses. Aquatic Conservation 26: 674-688. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2578 Whitford M & Klimley A. P. An overview of behavioral, physiological, and environmental sensors used in animal biotelemetry and biologging studies. Animal Biotelemetry, 7: 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40317-019-0189-z Wooller R.D., Bradley J. S. & Croxall J. P. 1992. Long-term population studies of seabirds. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 7: 111-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(92)90143-y Wunderle J. M. 1991. Age-specific foraging proficiency in birds. Current Ornithology, 8: 273-324. | The challenges of independence: ontogeny of at-sea behaviour in a long-lived seabird | Karine Delord, Henri Weimerskirch, Christophe Barbraud | <p style="text-align: justify;">The transition to independent foraging represents an important developmental stage in the life cycle of most vertebrate animals. Juveniles differ from adults in various life history traits and tend to survive less w... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Foraging, Ontogeny | Blandine Doligez | 2021-10-26 07:51:49 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive successAinhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus https://doi.org/10.1101/629931Improving our knowledge of species interaction networksRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers

Ecosystems shelter a huge number of species, continuously interacting. Each species interact in various ways, with trophic interactions, but also non-trophic interactions, not mentioning the abiotic and anthropogenic interactions. In particular, pollination, competition, facilitation, parasitism and many other interaction types are simultaneously present at the same place in terrestrial ecosystems [1-2]. For this reason, we need today to improve our understanding of such complex interaction networks to later anticipate their responses. This program is a huge challenge facing ecologists and they today join their forces among experimentalists, theoreticians and modelers. While some of us struggle in theoretical and modeling dimensions [3-4], some others perform brilliant works to observe and/or experiment on the same ecological objects [5-6]. References [1] Campbell, C., Yang, S., Albert, R., and Shea, K. (2011). A network model for plant–pollinator community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(1), 197-202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008204108 | Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive success | Ainhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus | <p>Declines in pollinator diversity and abundance have been reported across different regions, with implications for the reproductive success of plant species. However, research has focused primarily on pairwise plant-pollinator interactions, larg... |  | Ecosystem functioning, Interaction networks, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | Nicolas Deguines | 2019-05-07 17:03:23 | View |

29 Aug 2023

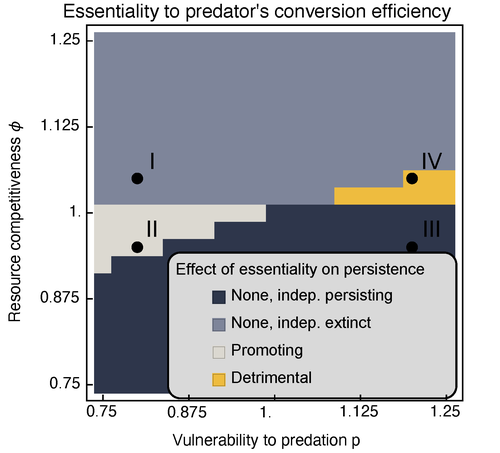

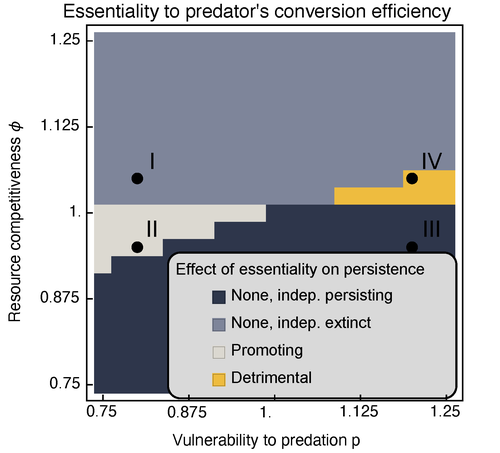

Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food websMichael Raatz https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839High-order interactions in food webs may strongly impact persistence of speciesRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jean-Christophe POGGIALE and 1 anonymous reviewer

Michael Raatz (2023) provides here a relevant exploration of higher-order interactions, i.e. interactions involving more than two related species (Terry et al. 2019), in the case of food web and competition interactions. More precisely, he shows by modeling that essential resources may significantly mediate focal species' persistence. Simultaneously, the provision of essential resources may strongly affect the resulting community structure, by driving to extinction first the predator and then, depending on the higher-order interaction, potentially also the associated competitor. Today, all ecologists should be aware of the potential effects of high-order interactions on species' (and likely on ecosystem's) fate (Golubski et al. 2016, Grilli et al. 2017). Yet, we should soon be prepared to include any high-order interaction into any interaction network (i.e. not only between species, but also between species and abiotic components, and between biotic, anthropogenic and abiotic components too). For this purpose, we will need innovative approaches such as hypergraphs (Golubski et al. 2016) and discrete-event models (Gaucherel and Pommereau 2019, Thomas et al. 2022) able to manage highly complex interactions, with numerous interacting components and variables. Such a rigorous study is a necessary and preliminary step in taking into account such a higher complexity. References Gaucherel, C. and F. Pommereau. 2019. Using discrete systems to exhaustively characterize the dynamics of an integrated ecosystem. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 00:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13242 Golubski, A. J., E. E. Westlund, J. Vandermeer, and M. Pascual. 2016. Ecological Networks over the Edge: Hypergraph Trait-Mediated Indirect Interaction (TMII) Structure trends in Ecology & Evolution 31:344-354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2016.02.006 Grilli, J., G. Barabas, M. J. Michalska-Smith, and S. Allesina. 2017. Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature 548:210-213. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23273 Raatz, M. 2023. Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.525839 Terry, J. C. D., R. J. Morris, and M. B. Bonsall. 2019. Interaction modifications lead to greater robustness than pairwise non-trophic effects in food webs. Journal of Animal Ecology 88:1732-1742. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13057 Thomas, C., M. Cosme, C. Gaucherel, and F. Pommereau. 2022. Model-checking ecological state-transition graphs. PLoS Computational Biology 18:e1009657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009657 | Provision of essential resources as a persistence strategy in food webs | Michael Raatz | <p style="text-align: justify;">Pairwise interactions in food webs, including those between predator and prey are often modulated by a third species. Such higher-order interactions are important structural components of natural food webs that can ... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Competition, Ecological stoichiometry, Food webs, Interaction networks, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | 2023-02-23 17:48:26 | View | |

25 May 2021

Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assemblyCaio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho https://doi.org/10.1101/869966Environmental heterogeneity drives phytoplankton community assembly patterns in a tropical riverine systemRecommended by Cédric Hubas and Eric Goberville and Eric Goberville based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy based on reviews by Eric Goberville and Dominique Lamy

What predisposes two individuals to form and maintain a relationship is a fundamental question. Using facial recognition to see whether couples' faces change over time to become more and more similar, psychology researchers have concluded that couples tend to be formed from the start between people whose faces are more similar than average [1]. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together. And what about in nature? Are these rules of assembly valid for communities of different species? In his seminal contribution, Robert MacArthur (1984) wrote ‘To do science is to search for repeated patterns’ [2]. Identifying the mechanisms that govern the arrangement of life is a hot research topic in the field of ecology for decades, and an absolutely essential prerequisite to answer the outstanding question of what shape ecological patterns in multi-species communities such as species-area relationships, relative species abundances, or spatial and temporal turnover of community composition; amid others [3]. To explain ecological patterns in nature, some rely on the concept that every species - through evolutionary processes and the acquisition of a unique set of traits that allow a species to be adapted to its abiotic and biotic environment - occupies a unique niche: Species coexistence comes as the result of niche differentiation [4,5]. Such a view has been challenged by the recognition of the key role of neutral processes [6], however, in which demographic stochasticity contributes to shape multi-species communities and to explain why congener species coexist much more frequently than expected by chance [7,8]. While the niche-based and neutral theories appear seemingly opposed at first sight [9], the dichotomy may be more philosophical than empirical [4,5]. Many examples have come to support that both concepts are not incompatible as they together influence the structure, diversity and functioning of communities [10], and are simply extreme cases of a continuum [11]. From this perspective, extrinsic factors, i.e., environmental heterogeneity, may influence the location of a given community along the niche-neutrality continuum. The walk of species in nature is therefore neither random nor ecologically predestined. In microbial assemblages, the co-existence of these two antagonistic mechanisms has been shown both theoretically and empirically. It has been shown that a combination of stabilising (niche) and equalising (neutral) mechanisms was responsible for the existence of groups of coexistent species (clumps) in a phytoplankton rich community [12]. Analysing interannual changes (2003-2009) in the weekly abundance of diatoms and dinoflagellates located in a temperate coastal ecosystem of the Western English Channel, Mutshinda et al. [13] found a mixture of biomass dynamics consistent with the neutrality-niche continuum hypothesis. While niche processes explained the dynamic of phytoplankton functional groups (i.e., diatoms vs. dinoflagellates) in terms of biomass, neutral processes mainly dominated - 50 to 75% of the time - the dynamics at the species level within functional groups [13]. From one endpoint to another, defining the location of a community along the continuum is all matter of scale [4,11]. In their study, testing predictions made by an emergent neutrality model, Graco-Roza et al. [14] provide empirical evidence that neutral and niche processes joined together to shape and drive planktonic communities in a riverine ecosystem. Body size - the 'master trait' - is used here as a discriminant ecological dimension along the niche axis. From their analysis, they not only show that the specific abundance is organised in clumps and gaps along the niche axis, but also reveal that different clumps exist along the river course. They identify two main clumps in body size - with species belonging to three different morphologically-based functional groups - and characterise that among-species differences in biovolume are driven by functional redundancy at the clump level; species functional distinctiveness being related to the relative biovolume of species. By grouping their variables according to seasons (cold-dry vs. warm-wet) or river elevation profile (upper, medium and lower course), they hereby highlight how environmental heterogeneity contributes to shape species assemblages and their dynamics and conclude that emergent neutrality models are a powerful approach to explain species coexistence; and therefore ecological patterns. References [1] Tea-makorn PP, Kosinski M (2020) Spouses’ faces are similar but do not become more similar with time. Scientific Reports, 10, 17001. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73971-8. [2] MacArthur RH (1984) Geographical Ecology: Patterns in the Distribution of Species. Princeton University Press. [3] Vellend M (2020) The Theory of Ecological Communities (MPB-57). Princeton University Press. [4] Wennekes PL, Rosindell J, Etienne RS (2012) The Neutral—Niche Debate: A Philosophical Perspective. Acta Biotheoretica, 60, 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10441-012-9144-6. [5] Gravel D, Guichard F, Hochberg ME (2011) Species coexistence in a variable world. Ecology Letters, 14, 828–839. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01643.x. [6] Hubbell SP (2001) The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography (MPB-32). Princeton University Press. [7] Leibold MA, McPeek MA (2006) Coexistence of the Niche and Neutral Perspectives in Community Ecology. Ecology, 87, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1399:COTNAN]2.0.CO;2. [8] Pielou EC (1977) The Latitudinal Spans of Seaweed Species and Their Patterns of Overlap. Journal of Biogeography, 4, 299–311. https://doi.org/10.2307/3038189. [9] Holt RD (2006) Emergent neutrality. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21, 531–533. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.003. [10] Scheffer M, Nes EH van (2006) Self-organized similarity, the evolutionary emergence of groups of similar species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 6230–6235. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0508024103. [11] Gravel D, Canham CD, Beaudet M, Messier C (2006) Reconciling niche and neutrality: the continuum hypothesis. Ecology Letters, 9, 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00884.x. [12] Vergnon R, Dulvy NK, Freckleton RP (2009) Niches versus neutrality: uncovering the drivers of diversity in a species-rich community. Ecology Letters, 12, 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01364.x. [13] Mutshinda CM, Finkel ZV, Widdicombe CE, Irwin AJ (2016) Ecological equivalence of species within phytoplankton functional groups. Functional Ecology, 30, 1714–1722. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12641. [14] Graco-Roza C, Segura AM, Kruk C, Domingos P, Soininen J, Marinho MM (2021) Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly. bioRxiv, 869966, ver. 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/869966

| Clumpy coexistence in phytoplankton: The role of functional similarity in community assembly | Caio Graco-Roza, Angel M. Segura, Carla Kruk, Patricia Domingos, Janne Soininen, Marcelo M. Marinho | <p style="text-align: justify;">Emergent neutrality (EN) suggests that species must be sufficiently similar or sufficiently different in their niches to avoid interspecific competition. Such a scenario results in a transient pattern with clumps an... |  | Coexistence, Community ecology, Theoretical ecology | Cédric Hubas | 2020-01-23 16:11:32 | View | |

02 Aug 2021

Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimationAline Migné, Gwendoline Duong, Dominique Menu, Dominique Davoult & François Gévaert https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03079617Towards a better understanding of the effects of self-shading on Fucus serratus populationsRecommended by Cédric Hubas based on reviews by Gwenael Abril, Francesca Rossi and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Gwenael Abril, Francesca Rossi and 1 anonymous reviewer

The importance of the vertical structure of vegetation cover for the functioning, management and conservation of ecosystems has received particular attention from ecologists in the last decades. Canopy architecture has many implications for light extinction coefficient, temperature variation reduction, self-shading which are all key parameters for the structuring and functioning of different ecosystems such as grasslands [1,2], forests [3,4], phytoplankton communities [5, 6], macroalgal populations [7] and even underwater animal forests such as octocoral communities [8]. This research topic, therefore, benefits from a large body of literature and the facilitative role of self-shadowing is no longer in question. However, it is always puzzling to note that some of the most common ecosystems turn out to be amongst the least known. This is precisely the case of the Fucus serratus communities which are widespread in Northeast Atlantic along the Atlantic coast of Europe from Svalbard to Portugal, as well as Northwest Atlantic & Gulf of St. Lawrence, easily accessible at low tide, but which have comparatively received less attention than more emblematic macro-algal communities such as Laminariales. The lack of attention paid to these most common Fucales is particularly critical as some species such as F. serratus are proving to be particularly vulnerable to environmental change, leading to a predicted northward retreat from its current southern boundary [9]. In the present study [10], the authors showed the importance of the vegetation cover in resisting tide-induced environmental stresses. The canopy of F. serratus mitigates stress levels experienced in the lower layers during emersion, while various acclimation strategies take over to maintain the photosynthetic apparatus in optimal conditions. They hereby highlight adaptation mechanisms to the extreme environment represented by the intertidal zone. These adaptation strategies were expected and similar mechanisms had been shown at the cellular level previously [11]. The earliest studies on the subject have shown that the structure of the bottom, the movement of water, and light availability all "influence the distribution of Fucaceae and disturb the regularity of their fine zonation, which itself is caused by the most important factor, desiccation", as Zaneveld states in his review [12]. He observed that the causes of the zonal distribution of marine algae are numerous, and identified several points of interest such as the relative period of emersion, the rapidity of desiccation, the loss of water, and the thickness of the cell walls. The present study thus highlights the existence of facilitative mechanisms associated with F. serratus canopy and nicely confirms previous work with in situ observations. It also highlights the importance of the vegetative cover in combating desiccation and introduces the dampening effect as a facilitating mechanism. The effect of the vegetation cover can sometimes even be felt beyond its immediate area of influence. A recent study shows that ground-level ozone is significantly reduced by the combined effects of canopy shading and turbulence [4]. Below the canopy, the light intensity becomes sufficiently low which inhibits ozone formation due to the decrease in the rates of hydroxyl radical formation and the rates of conversion of nitrogen dioxide to nitrogen oxide by photolysis. In addition, reductions in light levels associated with foliage promote ozone-destroying reactions between plant-emitted species, such as nitric oxide and/or alkenes, and ozone itself. The reduction in diffusivity slows the upward transport of surface emitted species, partially decoupling the area under the canopy from the rest of the atmosphere. By analogy with the work of Makar et al [4], and in the light of the results provided by the authors of this study, one may wonder whether the canopy dampening of F. serratus communities (and other common fucoids widely distributed on our coasts) might not also influence atmospheric chemistry, both at the Earth's surface and in the atmospheric boundary layer. The lack of accumulation of reactive oxygen species under the canopy found by the authors is consistent with this hypothesis and suggests that the damping effect of F. serratus may well have much wider consequences than expected. References [1] Jurik TW, Kliebenstein H (2000) Canopy Architecture, Light Extinction and Self-Shading of a Prairie Grass, Andropogon Gerardii. The American Midland Naturalist, 144, 51–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3083010 [2] Mitchley J, Willems JH (1995) Vertical canopy structure of Dutch chalk grasslands in relation to their management. Vegetatio, 117, 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00033256 [3] Kane VR, Gillespie AR, McGaughey R, Lutz JA, Ceder K, Franklin JF (2008) Interpretation and topographic compensation of conifer canopy self-shadowing. Remote Sensing of Environment, 112, 3820–3832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2008.06.001 [4] Makar PA, Staebler RM, Akingunola A, Zhang J, McLinden C, Kharol SK, Pabla B, Cheung P, Zheng Q (2017) The effects of forest canopy shading and turbulence on boundary layer ozone. Nature Communications, 8, 15243. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms15243 [5] Shigesada N, Okubo A (1981) Analysis of the self-shading effect on algal vertical distribution in natural waters. Journal of Mathematical Biology, 12, 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00276919 [6] Barros MP, Pedersén M, Colepicolo P, Snoeijs P (2003) Self-shading protects phytoplankton communities against H2O2-induced oxidative damage. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 30, 275–282. https://doi.org/10.3354/ame030275 [7] Ørberg SB, Krause-Jensen D, Mouritsen KN, Olesen B, Marbà N, Larsen MH, Blicher ME, Sejr MK (2018) Canopy-Forming Macroalgae Facilitate Recolonization of Sub-Arctic Intertidal Fauna and Reduce Temperature Extremes. Frontiers in Marine Science, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2018.00332 [8] Nelson H, Bramanti L (2020) From Trees to Octocorals: The Role of Self-Thinning and Shading in Underwater Animal Forests. In: Perspectives on the Marine Animal Forests of the World (eds Rossi S, Bramanti L), pp. 401–417. Springer International Publishing, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57054-5_12 [9] Jueterbock A, Kollias S, Smolina I, Fernandes JMO, Coyer JA, Olsen JL, Hoarau G (2014) Thermal stress resistance of the brown alga Fucus serratus along the North-Atlantic coast: Acclimatization potential to climate change. Marine Genomics, 13, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.margen.2013.12.008 [10] Migné A, Duong G, Menu D, Davoult D, Gévaert F (2021) Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimation. HAL, hal-03079617, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03079617 [11] Lichtenberg M, Kühl M (2015) Pronounced gradients of light, photosynthesis and O2 consumption in the tissue of the brown alga Fucus serratus. New Phytologist, 207, 559–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13396 [12] Zaneveld JS (1937) The Littoral Zonation of Some Fucaceae in Relation to Desiccation. Journal of Ecology, 25, 431–468. https://doi.org/10.2307/2256204 | Dynamics of Fucus serratus thallus photosynthesis and community primary production during emersion across seasons: canopy dampening and biochemical acclimation | Aline Migné, Gwendoline Duong, Dominique Menu, Dominique Davoult & François Gévaert | <p style="text-align: justify;">The brown alga <em>Fucus serratus</em> forms dense stands on the sheltered low intertidal rocky shores of the Northeast Atlantic coast. In the southern English Channel, these stands have proved to be highly producti... |  | Marine ecology | Cédric Hubas | 2021-01-05 16:24:02 | View | |

10 Jun 2018

A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis”Charpentier MJE, Kappeler PM https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.08151v3Does elevated parasite richness in the environment affect daily path length of animals or is it the converse? An answer bringing some new elements of discussionRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

In 2015, Brockmeyer et al. [1] suggested that mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx) may accept additional ranging costs to avoid heavily parasitized areas. Following this paper, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] questioned this interpretation and presented other hypotheses. To summarize, whilst Brockmeyer et al. [1] proposed that elevated daily path length may be a consequence of elevated parasite richness, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2] viewed it as a cause. In this current paper, Charpentier and Kappeler [3] respond to some of the criticisms by Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques and discuss the putative parsimony of the two competing scenarios. The manuscript is interesting and focuses on an important question concerning the discussion about the social organization and home range use in wild mandrills. This answer helps to move this debate forward and should stimulate more empirical studies of the role of environmentally-transmitted parasites in shaping ranging and movement patterns of wild vertebrates. Given the elements this paper brings to the topics, it should have been published in American Journal of Primatology, the journal that published the two previous articles. References [1] Brockmeyer, T., Kappeler, P. M., Willaume, E., Benoit, L., Mboumba, S., & Charpentier, M. J. E. (2015). Social organization and space use of a wild mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx) group. American Journal of Primatology, 77(10), 1036–1048. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22439 | A reply to “Ranging Behavior Drives Parasite Richness: A More Parsimonious Hypothesis” | Charpentier MJE, Kappeler PM | In a recent article, Bicca-Marques and Calegaro-Marques [2016] discussed the putative assumptions related to an interpretation we provided regarding an observed positive relationship between weekly averaged parasite richness of a group of mandrill... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Foraging, Host-parasite interactions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Zoology | Cédric Sueur | 2018-05-22 10:59:33 | View | |

29 Sep 2023

MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modellingOndřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.03.05.531080A deep learning model to unlock secrets of animal movement and behaviourRecommended by Cédric Sueur based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Jacob Davidson and 1 anonymous reviewer

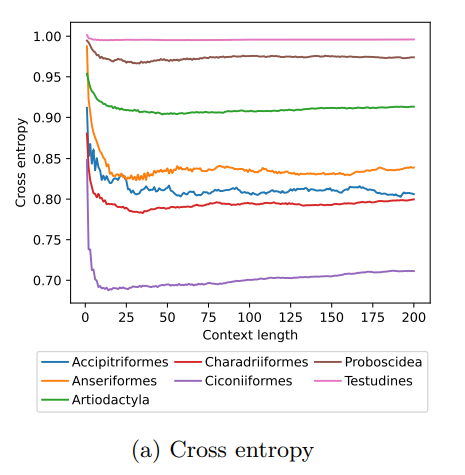

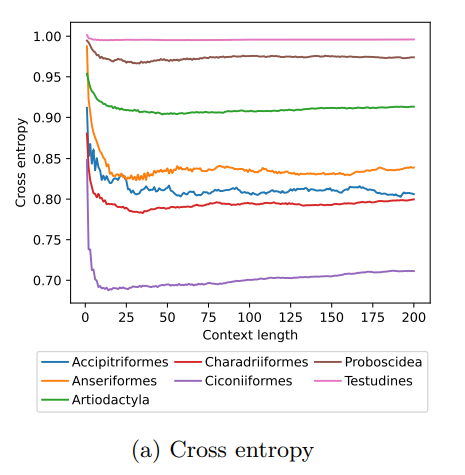

The study of animal movement is essential for understanding their behaviour and how ecological or global changes impact their routines [1]. Recent technological advancements have improved the collection of movement data [2], but limited statistical tools have hindered the analysis of such data [3–5]. Animal movement is influenced not only by environmental factors but also by internal knowledge and memory, which are challenging to observe directly [6,7]. Routine movement behaviours and the incorporation of memory into models remain understudied. Researchers have developed ‘MoveFormer’ [8], a deep learning-based model that predicts future movements based on past context, addressing these challenges and offering insights into the importance of different context lengths and information types. The model has been applied to a dataset of over 1,550 trajectories from various species, and the authors have made the MoveFormer source code available for further research. Inspired by the step-selection framework and efforts to quantify uncertainty in movement predictions, MoveFormer leverages deep learning, specifically the Transformer architecture, to encode trajectories and understand how past movements influence current and future ones – a critical question in movement ecology. The results indicate that integrating information from a few days to two or three weeks before the movement enhances predictions. The model also accounts for environmental predictors and offers insights into the factors influencing animal movements. Its potential impact extends to conservation, comparative analyses, and the generalisation of uncertainty-handling methods beyond ecology, with open-source code fostering collaboration and innovation in various scientific domains. Indeed, this method could be applied to analyse other kinds of movements, such as arm movements during tool use [9], pen movements, or eye movements during drawing [10], to better understand anticipation in actions and their intentionality. References 1. Méndez, V.; Campos, D.; Bartumeus, F. Stochastic Foundations in Movement Ecology: Anomalous Diffusion, Front Propagation and Random Searches; Springer Series in Synergetics; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; ISBN 978-3-642-39009-8. | MoveFormer: a Transformer-based model for step-selection animal movement modelling | Ondřej Cífka, Simon Chamaillé-Jammes, Antoine Liutkus | <p style="text-align: justify;">The movement of animals is a central component of their behavioural strategies. Statistical tools for movement data analysis, however, have long been limited, and in particular, unable to account for past movement i... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Habitat selection | Cédric Sueur | 2023-03-22 16:32:14 | View | |

12 Mar 2023

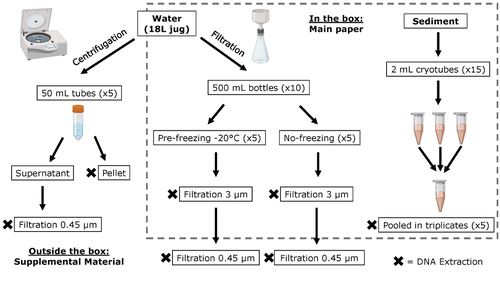

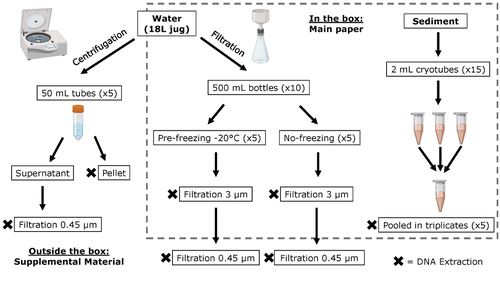

Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities.Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388Processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters from coastal lagoonsRecommended by Claudia Piccini based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Rutger De WitCoastal lagoons are among the most productive natural ecosystems on Earth. These relatively closed basins are important habitats and nursery for endemic and endangered species and are extremely vulnerable to nutrient input from the surrounding catchment; therefore, they are highly susceptible to anthropogenic influence, pollution and invasion (Pérez-Ruzafa et al., 2019). In general, coastal lagoons exhibit great spatial and temporal variability in their physicochemical water characteristics due to the sporadic mixing of freshwater with marine influx. One of the alternatives for monitoring communities or target species in aquatic ecosystems is the environmental DNA (eDNA), since overcomes some limitations from traditional methods and enables the investigation of multiple species from a single sample (Thomsen and Willerslev, 2015). In coastal lagoons, where the water turbidity is highly variable, there is a major challenge for monitoring the eDNA because filtering turbid water to obtain the eDNA is problematic (filters get rapidly clogged, there is organic and inorganic matter accumulation, etc.). The study by Turba et al. (2023) analyzes different ways of dealing with eDNA sampling and processing in turbid waters and sediments of coastal lagoons, and offers guidelines to obtain unbiased results from the subsequent sequencing using 12S (fish) and 16S (Bacteria and Archaea) universal primers. They analyzed the effect on taxa detection of: i) freezing or not prior to filtering; ii) freezing prior to centrifugation to obtain a sample pellet; and iii) using frozen sediment samples as a proxy of what happens in the water. The authors propose these different alternatives (freeze, do not freeze, sediment sampling) because they consider that they are the easiest to carry out. They found that freezing before filtering using a 3 µm pore size filter had no effects on community composition for either primer, and therefore it is a worthwhile approach for comparison of fish, bacteria and archaea in this kind of system. However, significantly different bacterial community composition was found for sediment compared to water samples. Also, in sediment samples the replicates showed to be more heterogeneous, so the authors suggest increasing the number of replicates when using sediment samples. Something that could be a concern with the study is that the rarefaction curves based on sequencing effort for each protocol did not saturate in any case, this being especially evident in sediment samples. The authors were aware of this, used the slopes obtained from each curve as a measure of comparison between samples and considering that the sequencing depth did not meet their expectations, they managed to achieve their goal and to determine which protocol is the most promising for eDNA monitoring in coastal lagoons. Although there are details that could be adjusted in relation to this item, I consider that the approach is promising for this type of turbid system. References Pérez-Ruzafa A, Campillo S, Fernández-Palacios JM, García-Lacunza A, García-Oliva M, Ibañez H, Navarro-Martínez PC, Pérez-Marcos M, Pérez-Ruzafa IM, Quispe-Becerra JI, Sala-Mirete A, Sánchez O, Marcos C (2019) Long-Term Dynamic in Nutrients, Chlorophyll a, and Water Quality Parameters in a Coastal Lagoon During a Process of Eutrophication for Decades, a Sudden Break and a Relatively Rapid Recovery. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2019.00026 Thomsen PF, Willerslev E (2015) Environmental DNA – An emerging tool in conservation for monitoring past and present biodiversity. Biological Conservation, 183, 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.11.019 Turba R, Thai GH, Jacobs DK (2023) Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. bioRxiv, 2022.06.17.495388, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.17.495388 | Different approaches to processing environmental DNA samples in turbid waters have distinct effects for fish, bacterial and archaea communities. | Rachel Turba, Glory H. Thai, and David K Jacobs | <p style="text-align: justify;">Coastal lagoons are an important habitat for endemic and threatened species in California that have suffered impacts from urbanization and increased drought. Environmental DNA has been promoted as a way to aid in th... |  | Biodiversity, Community genetics, Conservation biology, Freshwater ecology, Marine ecology, Molecular ecology | Claudia Piccini | David Murray-Stoker | 2022-06-20 20:31:51 | View |

24 Nov 2023

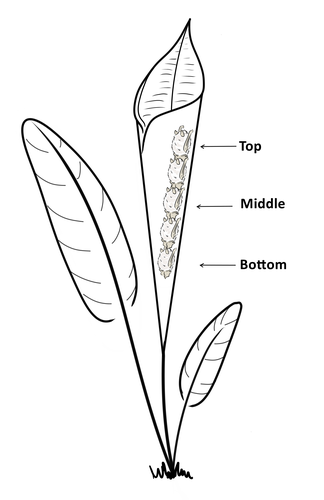

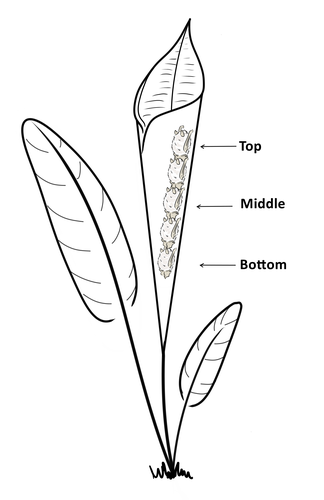

Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged batsGiada Giacomini, Silvia Chaves-Ramirez, Andres Hernandez-Pinson, Jose Pablo Barrantes, Gloriana Chaverri https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.04.515223Consistent individual differences in habitat use in a tropical leaf roosting batRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Annemarie van der Marel and 2 anonymous reviewersConsistent individual differences in habitat use are found across species and can play a role in who an individual mates with, their risk of predation, and their ability to compete with others (Stuber et al. 2022). However, the data informing such hypotheses come primarily from temperate regions (Stroud & Thompson 2019, Titley et al. 2017). This calls into question the generalizability of the conclusions from this research until further investigations can be conducted in tropical regions. Giacomini and colleagues (2023) tackled this task in an investigation of consistent individual differences in habitat use in the Central American tropics. They explored whether Spix’s disc-winged bats form positional hierarchies in roosts, which is an excellent start to learning more about the social behavior of this species - a species that is difficult to directly observe. They found that individual bats use their roosting habitat in predictable ways by positioning themselves consistently either in the bottom, middle, or top of the roost leaf. Individuals chose the same positions across time and across different roost sites. They also found that age and sex play a role in which sections individuals are positioned in. Their research shows that consistent individual differences in habitat use are present in a tropical system, and sets the stage for further investigations into social behavior in this species, particularly whether there is a dominance hierarchy among individuals and whether some positions in the roost are more protective and sought after than others. References Giacomini G, Chaves-Ramirez S, Hernandez-Pinson A, Barrantes JP, Chaverri G. (2023). Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged bats. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.04.515223 Stroud, J. T., & Thompson, M. E. (2019). Looking to the past to understand the future of tropical conservation: The importance of collecting basic data. Biotropica, 51(3), 293-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12665 Stuber, E. F., Carlson, B. S., & Jesmer, B. R. (2022). Spatial personalities: a meta-analysis of consistent individual differences in spatial behavior. Behavioral Ecology, 33(3), 477-486. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab147 Titley, M. A., Snaddon, J. L., & Turner, E. C. (2017). Scientific research on animal biodiversity is systematically biased towards vertebrates and temperate regions. PloS one, 12(12), e0189577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189577 | Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged bats | Giada Giacomini, Silvia Chaves-Ramirez, Andres Hernandez-Pinson, Jose Pablo Barrantes, Gloriana Chaverri | <p style="text-align: justify;">Individuals within both moving and stationary groups arrange themselves in a predictable manner; for example, some individuals are consistently found at the front of the group or in the periphery and others in the c... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure, Zoology | Corina Logan | 2022-11-05 17:39:35 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle