Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * ▲ | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 May 2023

Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new contextLogan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xsAn experiment to improve our understanding of the link between behavioral flexibility and innovativenessRecommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel, Andrea Griffin, Aliza le Roux and 1 anonymous reviewer

Whether individuals are able to cope with new environmental conditions, and whether this ability can be improved, is certainly of great interest in our changing world. One way to cope with new conditions is through behavioral flexibility, which can be defined as “the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances through packaging information and making it available to other cognitive processes” (Logan et al. 2023). Flexibility is predicted to be positively correlated with innovativeness, the ability to create a new behavior or use an existing behavior in a few situations (Griffin & Guez 2014). Coulon A (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Griffin, A. S., & Guez, D. (2014). Innovation and problem solving: A review of common mechanisms. Behavioural Processes, 109, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2014.08.027 Logan C, Rowney C, Bergeron L, Seitz B, Blaisdell A, Johnson-Ulrich Z, McCune K (2019) Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz B, Sevchik A, McCune KB (2023) Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context. EcoEcoRxiv, version 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/5z8xs | Behavioral flexibility is manipulable and it improves flexibility and innovativeness in a new context | Logan CJ, Lukas D, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, McCune KB | <p style="text-align: justify;">Behavioral flexibility, the ability to adapt behavior to new circumstances, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geographic range. Howev... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-01-13 19:08:52 | View | ||

28 Aug 2023

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30JBehavioral changes in the rapid geographic expansion of the great-tailed grackleRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer

While many species' populations are declining, primarily due to human-related impacts (McKnee et al., 2014), certain species have thrived by utilizing human-influenced environments, leading to their population expansion (Muñoz & Real, 2006). In this context, the capacity to adapt and modify behaviors in response to new surroundings is believed to play a crucial role in facilitating species' spread to novel areas (Duckworth & Badyaev, 2007). For example, an increase in innovative behaviors within recently established communities could aid in discovering previously untapped food resources, while a decrease in exploration might reduce the likelihood of encountering dangers in unfamiliar territories (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016). To investigate the contribution of these behaviors to rapid range expansions, it is essential to directly measure and compare behaviors in various populations of the species. The study conducted by Logan et al. (2023) aims to comprehend the role of behavioral changes in the range expansion of great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). To achieve this, the researchers compared the prevalence of specific behaviors at both the expansion's edge and its middle. Great-tailed grackles were chosen as an excellent model due to their behavioral adaptability, rapid geographic expansion, and their association with human-modified environments. The authors carried out a series of experiments in captivity using wild-caught individuals, following a detailed protocol. The study successfully identified differences in two of the studied behavioral traits: persistence (individuals participated in a larger proportion of trials) and flexibility variance (a component of the species' behavioral flexibility, indicating a higher chance that at least some individuals in the population could be more flexible). Notably, individuals at the edge of the population exhibited higher values of persistence and flexibility, suggesting that these behavioral traits might be contributing factors to the species' expansion. Overall, the study by Logan et al. (2023) is an excellent example of the importance of behavioral flexibility and other related behaviors in the process of species' range expansion and the significance of studying these behaviors across different populations to gain a better understanding of their role in the expansion process. Finally, it is important to underline that this study is part of a pre-registration that received an In Principle Recommendation in PCI Ecology (Sebastián-González 2020) where objectives, methodology, and expected results were described in detail. The authors have identified any deviation from the original pre-registration and thoroughly explained the reasons for their deviations, which were very clear. References Duckworth, R. A., & Badyaev, A. V. (2007). Coupling of dispersal and aggression facilitates the rapid range expansion of a passerine bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(38), 15017-15022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706174104 Griffin, A.S., Guez, D., Federspiel, I., Diquelou, M., Lermite, F. (2016). Invading new environments: A mechanistic framework linking motor diversity and cognition to establishment success. Biological Invasions and Animal Behaviour, 26e46. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139939492.004 Logan, C. J., McCune, K., LeGrande-Rolls, C., Marfori, Z., Hubbard, J., Lukas, D. 2023. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30J McKee, J. K., Sciulli, P. W., Fooce, C. D., & Waite, T. A. (2004). Forecasting global biodiversity threats associated with human population growth. Biological Conservation, 115(1), 161-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00099-5 Muñoz, A. R., & Real, R. (2006). Assessing the potential range expansion of the exotic monk parakeet in Spain. Diversity and Distributions, 12(6), 656-665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2006.00272.x Sebastián González, E. (2020) The role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansion. Peer Community in Ecology, 100062. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100062. Reviewers: Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of species to rapidly expand their geographic range. Great-tailed grackles (<em>Quiscalus mexi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | 2023-04-12 11:00:42 | View | ||

16 Oct 2018

Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus)Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4How empirical sciences may improve livestock welfare and help their managementRecommended by Marie Charpentier based on reviews by Alecia CARTER and 1 anonymous reviewerUnderstanding how livestock management is a source of social stress and disturbances for cattle is an important question with potential applications for animal welfare programs and sustainable development. In their article, Sosa and colleagues [1] first propose to evaluate the effects of individual characteristics on dyadic social relationships and on the social dynamics of four groups of cattle. Using network analyses, the authors provide an interesting and complete picture of dyadic interactions among groupmates. Although shown elsewhere, the authors demonstrate that individuals that are close in age and close in rank form stronger dyadic associations than other pairs. Second, the authors take advantage of some transfers of animals between groups -for management purposes- to assess how these transfers affect the social dynamics of groupmates. Their central finding is that the identity of transferred animals is a key-point. In particular, removing offspring strongly destabilizes the social relationships of mothers while adding a bull into a group also profoundly impacts female-female social relationships, as social networks before and after transfer of these key-animals are completely different. In addition, individuals, especially the young ones, that are transferred without familiar conspecifics take more time to socialize with their new group members than individuals transferred with familiar groupmates, generating a potential source of stress. Interestingly, the authors end up their article with some thoughts on the implications of their findings for animal welfare and ethics. This study provides additional evidence that empirical science has a major role to play in providing recommendations regarding societal questions such as livestock management and animal wellbeing. References [1] Sosa, S., Pelé, M., Debergue, E., Kuntz, C., Keller, B., Robic, F., Siegwalt-Baudin, F., Richer, C., Ramos, A., & Sueur C. (2018). Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus). arXiv:1805.11553v4 [q-bio.PE] peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. https://arxiv.org/abs/1805.11553v4 | Impact of group management and transfer on individual sociality in Highland cattle (Bos Taurus) | Sebastian Sosa, Marie Pelé, Elise Debergue, Cedric Kuntz, Blandine Keller, Florian Robic, Flora Siegwalt-Baudin, Camille Richer, Amandine Ramos, Cédric Sueur | The sociality of cattle facilitates the maintenance of herd cohesion and synchronisation, making these species the ideal choice for domestication as livestock for humans. However, livestock populations are not self-regulated, and farmers transfer ... | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure | Marie Charpentier | 2018-05-30 14:05:39 | View | ||

24 Nov 2023

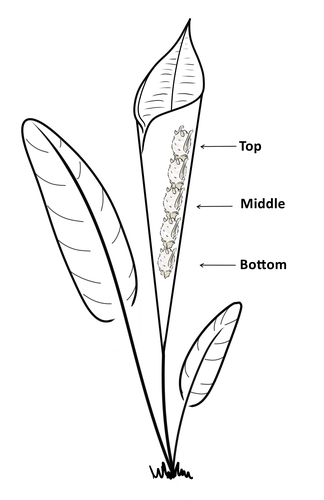

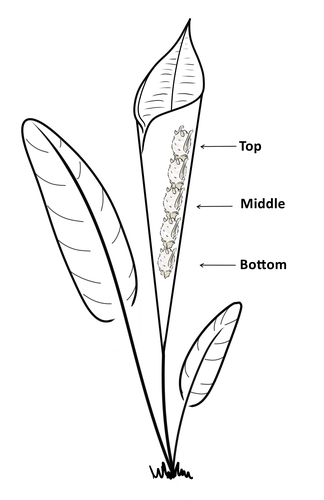

Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged batsGiada Giacomini, Silvia Chaves-Ramirez, Andres Hernandez-Pinson, Jose Pablo Barrantes, Gloriana Chaverri https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.04.515223Consistent individual differences in habitat use in a tropical leaf roosting batRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Annemarie van der Marel and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Annemarie van der Marel and 2 anonymous reviewers

Consistent individual differences in habitat use are found across species and can play a role in who an individual mates with, their risk of predation, and their ability to compete with others (Stuber et al. 2022). However, the data informing such hypotheses come primarily from temperate regions (Stroud & Thompson 2019, Titley et al. 2017). This calls into question the generalizability of the conclusions from this research until further investigations can be conducted in tropical regions. Giacomini and colleagues (2023) tackled this task in an investigation of consistent individual differences in habitat use in the Central American tropics. They explored whether Spix’s disc-winged bats form positional hierarchies in roosts, which is an excellent start to learning more about the social behavior of this species - a species that is difficult to directly observe. They found that individual bats use their roosting habitat in predictable ways by positioning themselves consistently either in the bottom, middle, or top of the roost leaf. Individuals chose the same positions across time and across different roost sites. They also found that age and sex play a role in which sections individuals are positioned in. Their research shows that consistent individual differences in habitat use are present in a tropical system, and sets the stage for further investigations into social behavior in this species, particularly whether there is a dominance hierarchy among individuals and whether some positions in the roost are more protective and sought after than others. References Giacomini G, Chaves-Ramirez S, Hernandez-Pinson A, Barrantes JP, Chaverri G. (2023). Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged bats. bioRxiv, https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.04.515223 Stroud, J. T., & Thompson, M. E. (2019). Looking to the past to understand the future of tropical conservation: The importance of collecting basic data. Biotropica, 51(3), 293-299. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12665 Stuber, E. F., Carlson, B. S., & Jesmer, B. R. (2022). Spatial personalities: a meta-analysis of consistent individual differences in spatial behavior. Behavioral Ecology, 33(3), 477-486. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arab147 Titley, M. A., Snaddon, J. L., & Turner, E. C. (2017). Scientific research on animal biodiversity is systematically biased towards vertebrates and temperate regions. PloS one, 12(12), e0189577. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189577 | Consistent individual positions within roosts in Spix's disc-winged bats | Giada Giacomini, Silvia Chaves-Ramirez, Andres Hernandez-Pinson, Jose Pablo Barrantes, Gloriana Chaverri | <p style="text-align: justify;">Individuals within both moving and stationary groups arrange themselves in a predictable manner; for example, some individuals are consistently found at the front of the group or in the periphery and others in the c... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Social structure, Zoology | Corina Logan | 2022-11-05 17:39:35 | View | |

29 Mar 2021

Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variationRicardo A. Segovia https://doi.org/10.1101/836338New light on the baseline importance of temperature for the origin of geographic species richness gradientsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers

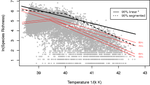

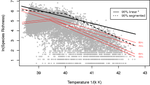

Whether environmental conditions –in particular energy and water availability– are sufficient to account for species richness gradients (e.g. Currie 1991), or the effects of other biotic and historical or regional factors need to be considered as well (e.g. Ricklefs 1987), was the subject of debate during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Francis & Currie 2003; Hawkins et al. 2003, 2006; Currie et al. 2004; Ricklefs 2004). The metabolic theory of ecology (Brown et al. 2004) provided a solid and well-rooted theoretical support for the preponderance of energy as the main driver for richness variations. As any good piece of theory, it provided testable predictions about the sign and shape (i.e. slope) of the relationship between temperature –a key aspect of ambient energy– and species richness. However, these predictions were not supported by empirical evaluations (e.g. Kreft & Jetz 2007; Algar et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 2007a), as the effects of a myriad of other environmental gradients, regional factors and evolutionary processes result in a wide variety of richness–temperature responses across different groups and regions (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Hortal et al. 2008). So, in a textbook example of how good theoretical work helps advancing science even if proves to be (partially) wrong, the evaluation of this aspect of the metabolic theory of ecology led to current understanding that, while species richness does respond to current climatic conditions, many other ecological, evolutionary and historical factors do modify such response across scales (see, e.g., Ricklefs 2008; Hawkins 2008; D’Amen et al. 2017). And the kinetic model linking mean annual temperature and species richness (Allen et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2004) was put aside as being, perhaps, another piece of the puzzle of the origin of current diversity gradients. Segovia (2021) puts together an elegant way of reinvigorating this part of the metabolic theory of ecology. He uses quantile regressions to model just the upper parts of the relationship between species richness and mean annual temperature, rather than modelling its central tendency through the classical linear regression family of methods –as was done in the past. This assumes that the baseline effect of ambient energy does produce the negative linear relationship between richness and temperature predicted by the kinetic model (Allen et al. 2002), but also that this effect only poses an upper limit for species richness, and the effects of other factors may result in lower levels of species co-occurrence, thus producing a triangular rather than linear relationship. The results of Segovia’s simple and elegant analytical design show unequivocally that the predictions of the kinetic model become progressively more explanatory towards the upper quartiles of the relationship between species richness and temperature along over 10,000 tree local inventories throughout the Americas, reaching over 70% of explanatory power for the upper 5% of the relationship (i.e. the 95% quantile). This confirms to a large extent his reformulation of the predictions of the kinetic model. Further, the neat study from Segovia (2021) also provides evidence confirming that the well-known spatial non-stationarity in the richness–temperature relationship (see Cassemiro et al. 2007) also applies to its upper-bound segment. Both the explanatory power and the slope of the relationship in the 95% upper quantile vary widely between biomes, reaching values similar to the predictions of the kinetic model only in cold temperate environments –precisely where temperature becomes more important than water availability as a constrain to plant life (O’Brien 1998; Hawkins et al. 2003). Part of these variations are indeed related with changes in water deficit and number of frost days along the XXth Century, as shown by the residuals of this paper (Segovia 2021) and a more detailed separate study (Segovia et al. 2020). This pinpoints the importance of the relative balance between water and energy as two of the main climatic factors constraining species diversity gradients, confirming the value of hypotheses that date back to Humboldt’s work (see Hawkins 2001, 2008). There is however a significant amount of unexplained variation in Segovia’s analyses, in particular in the progressive departure of the predictions of the kinetic model as we move towards the tropics, or downwards along the lower quantiles of the richness–temperature relationship. This calls for a deeper exploration of the factors that modify the baseline relationship between richness and energy, opening a new avenue for the macroecological investigation of how different forces and processes shape up geographical diversity gradients beyond the mere energetic constrains imposed by the basal limitations of multicellular life on Earth. References Algar, A.C., Kerr, J.T. and Currie, D.J. (2007) A test of Metabolic Theory as the mechanism underlying broad-scale species-richness gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 170-178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00275.x Allen, A.P., Brown, J.H. and Gillooly, J.F. (2002) Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science, 297, 1545-1548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072380 Brown, J.H., Gillooly, J.F., Allen, A.P., Savage, V.M. and West, G.B. (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology, 85, 1771-1789. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-9000 Cassemiro, F.A.d.S., Barreto, B.d.S., Rangel, T.F.L.V.B. and Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. (2007) Non-stationarity, diversity gradients and the metabolic theory of ecology. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 820-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00332.x Currie, D.J. (1991) Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist, 137, 27-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/285144 Currie, D.J., Mittelbach, G.G., Cornell, H.V., Field, R., Guegan, J.-F., Hawkins, B.A., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2004) Predictions and tests of climate-based hypotheses of broad-scale variation in taxonomic richness. Ecology Letters, 7, 1121-1134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00671.x D'Amen, M., Rahbek, C., Zimmermann, N.E. and Guisan, A. (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Francis, A.P. and Currie, D.J. (2003) A globally consistent richness-climate relationship for Angiosperms. American Naturalist, 161, 523-536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/368223 Hawkins, B.A. (2001) Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8 Hawkins, B.A. (2008) Recent progress toward understanding the global diversity gradient. IBS Newsletter, 6.1, 5-8. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr2k1dd Hawkins, B.A., Field, R., Cornell, H.V., Currie, D.J., Guégan, J.-F., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Mittelbach, G.G., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E., Porter, E.E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2003) Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology, 84, 3105-3117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8006 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Jaramillo, C.A. and Soeller, S.A. (2006) Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 770-780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01452.x Hawkins, B.A., Albuquerque, F.S., Araújo, M.B., Beck, J., Bini, L.M., Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J., Castro Parga, I., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Ferrer-Castán, D., Field, R., Gómez, J.F., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Kitching, I.J., León-Cortés, J.L., et al. (2007a) A global evaluation of metabolic theory as an explanation for terrestrial species richness gradients. Ecology, 88, 1877-1888. doi:10.1890/06-1444.1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1444.1 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Bini, L.M., Araújo, M.B., Field, R., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Rahbek, C., Rodríguez, M.Á. and Sanders, N.J. (2007b) Metabolic theory and diversity gradients: Where do we go from here? Ecology, 88, 1898–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-2141.1 Hortal, J., Rodríguez, J., Nieto-Díaz, M. and Lobo, J.M. (2008) Regional and environmental effects on the species richness of mammal assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 35, 1202–1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01850.x Kreft, H. and Jetz, W. (2007) Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104, 5925-5930. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608361104 O'Brien, E. (1998) Water-energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 379-398. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x Ricklefs, R.E. (1987) Community diversity: Relative roles of local and regional processes. Science, 235, 167-171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4785.167 Ricklefs, R.E. (2004) A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 7, 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00554.x Ricklefs, R.E. (2008) Disintegration of the ecological community. American Naturalist, 172, 741-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/593002 Segovia, R.A. (2021) Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation. bioRxiv, 836338, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/836338 Segovia, R.A., Pennington, R.T., Baker, T.R., Coelho de Souza, F., Neves, D.M., Davis, C.C., Armesto, J.J., Olivera-Filho, A.T. and Dexter, K.G. (2020) Freezing and water availability structure the evolutionary diversity of trees across the Americas. Science Advances, 6, eaaz5373. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5373 | Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation | Ricardo A. Segovia | <p>The kinetic hypothesis of biodiversity proposes that temperature is the main driver of variation in species richness, given its exponential effect on biological activity and, potentially, on rates of diversification. However, limited support fo... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Botany, Macroecology, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2019-11-10 20:56:40 | View | |

03 Mar 2022

Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than its age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea)sylvain blouet, Katell Guizien, lorenzo Bramanti https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.08.463669A longer-term view on benthic communities on artificial reefs: it’s all about locationRecommended by James Davis Reimer based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersIn this study by Blouet, Bramanti, and Guizen (2022), the authors aim to tackle a long-standing data gap regarding research on marine benthic communities found on artificial reefs. The study is well thought out, and should serve as an important reference on this topic going forward. Blouet S, Bramanti L, Guizien K (2022) Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than shape, age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea). bioRxiv, 2021.10.08.463669, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.08.463669 | Artificial reefs geographical location matters more than its age and depth for sessile invertebrate colonization in the Gulf of Lion (NorthWestern Mediterranean Sea) | sylvain blouet, Katell Guizien, lorenzo Bramanti | <p>Artificial reefs (ARs) have been used to support fishing activities. Sessile invertebrates are essential components of trophic networks within ARs, supporting fish productivity. However, colonization by sessile invertebrates is possible only af... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Colonization, Ecological successions, Life history, Marine ecology | James Davis Reimer | 2021-10-11 10:21:36 | View | |

30 Sep 2020

How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessmentFlorence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.02.129536Citizen science contributes to SDM validationRecommended by Francisco Lloret based on reviews by Maria Angeles Perez-Navarro and 1 anonymous reviewerCitizen science is becoming an important piece for the acquisition of scientific knowledge in the fields of natural sciences, and particularly in the inventory and monitoring of biodiversity (McKinley et al. 2017). The information generated with the collaboration of citizens has an evident importance in conservation, by providing information on the state of populations and habitats, helping in mitigation and restoration actions, and very importantly contributing to involve society in conservation (Brown and Williams 2019).

An obvious advantage of these initiatives is the ability to mobilize human resources on a large territorial scale and in the medium term, which would otherwise be difficult to finance. The resulting increasing information then can be processed with advanced computational techniques (Hochachka et al 2012; Kelling et al. 2015), thus improving our interpretation of the distribution of species. Specifically, the ability to obtain information on a large territorial scale can be integrated into studies based on Species Distribution Models SDMs. One of the common problems with SDMs is that they often work from species occurrences that have been opportunistically recorded, either by professionals or amateurs. A great challenge for data obtained from non-professional citizens, however, remains to ensure its standardization and quality (Kosmala et al. 2016). This requires a clear and effective design, solid volunteer training, and a high level of coordination that turns out to be complex (Brown and Williams 2019). Finally, it is essential to perform a quality validation following scientifically recognized standards, since they are often conditioned by errors and biases in obtaining information (Bird et al. 2014). There are two basic approaches to obtain the necessary data for this validation: getting it from an external source (external validation), or allocating a part of the database itself (internal validation or cross-validation) to this function. References [1] Bird TJ et al. (2014) Statistical solutions for error and bias in global citizen science datasets. Biological Conservation 173: 144-154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.07.037 | How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessment | Florence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon | <p>Species distribution models (SDM) have been increasingly developed in recent years but their validity is questioned. Their assessment can be improved by the use of independent data but this can be difficult to obtain and prohibitive to collect.... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Francisco Lloret | 2020-06-03 09:36:34 | View | ||

31 May 2023

Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibiansMatutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425Amphibians under scrutiny - When human-dominated landscape mosaics are not in full compliance with their ecological requirementsRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer

Among vertebrates, amphibians are one of the most diverse groups with more than 7,000 known species. Amphibians occupy various ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, and freshwater habitats. Amphibians are known to be highly sensitive to changes in their environment, particularly to water quality and habitat degradation, so that monitoring abundance of amphibian populations can provide early warning signs of ecosystem disturbances that may also affect other organisms including humans (Bishop et al., 2012). Accordingly, efforts in habitat preservation and sustainable land and water management are necessary to safeguard amphibian populations. In this context, Matutini et al. (2023) compared ecological requirements of amphibian species with the quality of agricultural landscape mosaics. Doing so, they identified critical gaps in existing conservation tools that include protected areas, green infrastructures, and inventoried sites. Matutini et al. (2023) focused on nine amphibian species in the Pays-de-la-Loire region where the landscape has been fashioned over the years by human activities. Three of the chosen amphibian species are living in a dense hedgerow mosaic landscape, while five others are more generalists. Matutini et al. (2023) established multi-species habitat suitability maps, together with their levels of confidence, by combining single species maps with a probabilistic stacking method at 500-m resolution. From these maps, habitats were classified in five categories, from not suitable to highly suitable. Then, the circuit theory was used to map the potential connections between each highly suitable patch at the regional scale. Finally, comparing suitability maps with existing conservation tools, Matutini et al. (2023) were able to assess their coverage and efficiency. Whatever their species status (endangered or not), Matutini et al. (2023) highlighted some discrepancies between the ecological requirements of amphibians in terms of habitat quality and the conservation tools of the landscape mosaic within which they are evolving. More specifically, Matutini et al. (2023) found that protected areas and inventoried sites covered only a small proportion of highly suitable habitats, while green infrastructures covered around 50% of the potential habitat for amphibian species. Such a lack of coverage and efficiency of protected areas brings to light that geographical sites with amphibian conservation challenges are known but not protected. Regarding the landscape fragmentation, Matutini et al. (2023) found that generalist amphibian species have a more homogeneous distribution of suitable habitats at the regional scale. They also identified two bottlenecks between two areas of suitable habitats, a situation that could prove critical to amphibian movements if amphibians were forced to change habitats to global change. In conclusion, Matutini et al. (2023) bring convincing arguments in support of land-use species-conservation planning based on a better consideration of human-dominated landscape mosaics in full compliance with ecological requirements of the species that inhabit the regions concerned. ReferencesBishop, P.J., Angulo, A., Lewis, J.P., Moore, R.D., Rabb, G.B., Moreno, G., 2012. The Amphibian Extinction Crisis - what will it take to put the action into the Amphibian Conservation Action Plan? Sapiens - Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society 5, 1–16. http://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1406 Matutini, F., Baudry, J., Fortin, M.-J., Pain, G., Pithon, J., 2023. Conservation networks do not match ecological requirements of amphibians. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425 | Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibians | Matutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Amphibians are among the most threatened taxa as they are highly sensitive to habitat degradation and fragmentation. They are considered as model species to evaluate habitats quality in agricultural landscapes. I... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-09-20 14:40:03 | View | ||

12 Oct 2020

Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predationAlex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.15.042317Tree diversity is associated with reduced herbivory in urban forestRecommended by Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer and Ian Pearse based on reviews by Ian Pearse and Freerk MollemanUrban ecology, the study of ecological systems in our increasingly urbanized world, is crucial to planning and redesigning cities to enhance ecosystem services (Kremer et al. 2016), human health and well-being and further conservation goals (Dallimer et al. 2012). Urban trees are a crucial component of urban streets and parks that provide shade and cooling through evapotranspiration (Fung and Jim 2019), improve air quality (Lai and Kontokosta 2019), help control storm water (Johnson and Handel 2016), and conserve wildlife (Herrmann et al. 2012; de Andrade et al. 2020). References Airola, D. and Greco, S. (2019). Birds and oaks in California’s urban forest. Int. Oaks, 30, 109–116. | Insect herbivory on urban trees: Complementary effects of tree neighbours and predation | Alex Stemmelen, Alain Paquette, Marie-Lise Benot, Yasmine Kadiri, Hervé Jactel, Bastien Castagneyrol | <p>Insect herbivory is an important component of forest ecosystems functioning and can affect tree growth and survival. Tree diversity is known to influence insect herbivory in natural forest, with most studies reporting a decrease in herbivory wi... |  | Biodiversity, Biological control, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Herbivory | Ruth Arabelle Hufbauer | 2020-04-20 13:49:36 | View | |

26 May 2021

Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunitiesCamille Saade, Sonia Kéfi, Claire Gougat-Barbera, Benjamin Rosenbaum, and Emanuel A. Fronhofer https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.03.409524Unity makes strength: clustered extinctions have stronger, longer-lasting effects on metacommunities dynamicsRecommended by Elodie Vercken based on reviews by David Murray-Stoker and Frederik De LaenderIn this article, Saade et al. (2021) investigate how the rate of local extinctions and their spatial distribution affect recolonization dynamics in metacommunities. They use an elegant combination of microcosm experiments with metacommunities of freshwater ciliates and mathematical modelling mirroring their experimental system. Their main findings are (i) that local patch extinctions increase both local (α-) and inter-patch (β-) diversity in a transient way during the recolonization process, (ii) that these effects depend more on the spatial distribution of extinctions (dispersed or clustered) than on their amount, and (iii) that they may spread regionally. A major strength of this study is that it highlights the importance of considering the spatial structure explicitly. Recent work on ecological networks has shown repeatedly that network structure affects the propagation of pathogens (Badham and Stocker 2010), invaders (Morel-Journel et al. 2019), or perturbation events (Gilarranz et al. 2017). Here, the spatial structure of the metacommunity is a regular grid of patches, but the distribution of extinction events may be either regularly dispersed (i.e., extinct patches are distributed evenly over the grid and are all surrounded by non-extinct patches only) or clustered (all extinct patches are neighbours). This has a direct effect on the neighbourhood of perturbed patches, and because perturbations have mostly local effects, their recovery dynamics are dominated by the composition of this immediate neighbourhood. In landscapes with dispersed extinctions, the neighbourhood of a perturbed patch is not affected by the amount of extinctions, and neither is its recovery time. In contrast, in landscapes with clustered extinctions, the amount of extinctions affects the depth of the perturbed area, which takes longer to recover when it is larger. Interestingly, the spatial distribution of extinctions here is functionally equivalent to differences in connectivity between perturbed and unperturbed patches, which results in contrasted “rescue recovery” and “mixing recovery” regimes as described by Zelnick et al. (2019).

Levins R (1969) Some Demographic and Genetic Consequences of Environmental Heterogeneity for Biological Control1. Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America, 15, 237–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/besa/15.3.237 Ruokolainen L (2013) Spatio-Temporal Environmental Correlation and Population Variability in Simple Metacommunities. PLOS ONE, 8, e72325. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0072325 Saade C, Kefi S, Gougat-Barbera C, Rosenbaum B, Fronhofer EA (2021) Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunities. bioRxiv, 2020.12.03.409524, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.03.409524 | Spatial distribution of local patch extinctions drives recovery dynamics in metacommunities | Camille Saade, Sonia Kéfi, Claire Gougat-Barbera, Benjamin Rosenbaum, and Emanuel A. Fronhofer | <p style="text-align: justify;">Human activities lead more and more to the disturbance of plant and animal communities with local extinctions as a consequence. While these negative effects are clearly visible at a local scale, it is less clear how... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Colonization, Community ecology, Competition, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Elodie Vercken | 2020-12-08 15:55:20 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle