Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

01 Mar 2019

Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild birdAdèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts https://doi.org/10.1101/323311The global change of species interactionsRecommended by Jan Hrcek based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersWhat kinds of studies are most needed to understand the effects of global change on nature? Two deficiencies stand out: lack of long-term studies [1] and lack of data on species interactions [2]. The paper by Mennerat and colleagues [3] is particularly valuable because it addresses both of these shortcomings. The first one is obvious. Our understanding of the impact of climate on biota improves with longer times series of observations. Mennerat et al. [3] analysed an impressive 18-year series from multiple sites to search for trends in parasitism rates across a range of temperatures. The second deficiency (lack of species interaction data) is perhaps not yet fully appreciated, despite studies pointing this out ten years ago [2,4]. The focus is often on species range limits and how taking species interactions into account changes species range predictions based on climate alone (climate envelope models; [5]). But range limits are not everything, as the function of a species (or community, network, etc.) ultimately depends on the strengths of species interactions and not only on the presence or absence of a given species [2,4]. Mennerat et al. [3] show that in the case of birds and their nest parasites, it is the strength of the interaction that has changed, while the species involved stayed the same. Mennerat et al. [3] found nest parasitism to increase with temperature at the nestling stage. They have also searched for trends of parasitism dynamics dependence on the host, but did not find any, probably because the nest parasites are generalists and attack other bird species within the study sites. This study thus draws attention to wider networks of interacting species, and we urgently need more data to predict how interaction networks will rewire with progressing environmental change [6,7]. References [1] Lindenmayer, D.B., Likens, G.E., Andersen, A., Bowman, D., Bull, C.M., Burns, E., et al. (2012). Value of long-term ecological studies. Austral Ecology, 37(7), 745–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9993.2011.02351.x | Parasite intensity is driven by temperature in a wild bird | Adèle Mennerat, Anne Charmantier, Sylvie Hurtrez-Boussès, Philippe Perret, Marcel M Lambrechts | <p>Increasing awareness that parasitism is an essential component of nearly all aspects of ecosystem functioning, as well as a driver of biodiversity, has led to rising interest in the consequences of climate change in terms of parasitism and dise... |  | Climate change, Evolutionary ecology, Host-parasite interactions, Parasitology, Zoology | Jan Hrcek | 2018-05-17 14:37:14 | View | |

12 Aug 2021

A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm callSamantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5Does the active vocabulary in Great-tailed Grackles supports their range expansion? New study will find outRecommended by Jan Oliver Engler based on reviews by Guillermo Fandos and 2 anonymous reviewersAlarm calls are an important acoustic signal that can decide the life or death of an individual. Many birds are able to vary their alarm calls to provide more accurate information on e.g. urgency or even the type of a threatening predator. According to the acoustic adaptation hypothesis, the habitat plays an important role too in how acoustic patterns get transmitted. This is of particular interest for range-expanding species that will face new environmental conditions along the leading edge. One could hypothesize that the alarm call repertoire of a species could increase in newly founded ranges to incorporate new habitats and threats individuals might face. Hence selection for a larger active vocabulary might be beneficial for new colonizers. Using the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) as a model species, Samantha Bowser from Arizona State University and Maggie MacPherson from Louisiana State University want to find out exactly that. The Great-Tailed Grackle is an appropriate species given its high vocal diversity. Also, the species consists of different subspecies that show range expansions along the northern range edge yet to a varying degree. Using vocal experiments and field recordings the researchers have a high potential to understand more about the acoustic adaptation hypothesis within a range dynamic process. Over the course of this assessment, the authors incorporated the comments made by two reviewers into a strong revision of their research plans. With that being said, the few additional comments made by one of the initial reviewers round up the current stage this interesting research project is in. To this end, I can only fully recommend the revised research plan and am much looking forward to the outcomes from the author’s experiments, modeling, and field data. With the suggestions being made at such an early stage I firmly believe that the final outcome will be highly interesting not only to an ornithological readership but to every ecologist and biogeographer interested in drivers of range dynamic processes. References Bowser, S., MacPherson, M. (2021). A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call. In principle recommendation by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/2UFJ5. Version 3 | A study on the role of social information sharing leading to range expansion in songbirds with large vocal repertoires: Enhancing our understanding of the Great-Tailed Grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) alarm call | Samantha Bowser, Maggie MacPherson | <p>The acoustic adaptation hypothesis posits that animal sounds are influenced by the habitat properties that shape acoustic constraints (Ey and Fischer 2009, Morton 2015, Sueur and Farina 2015).Alarm calls are expected to signal important habitat... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Coexistence, Dispersal & Migration, Habitat selection, Landscape ecology | Jan Oliver Engler | Darius Stiels, Anonymous | 2020-12-01 18:11:02 | View |

14 May 2019

Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imagingMarie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches https://doi.org/10.1101/425561OB-GYN for salmon parrsRecommended by Jean-Olivier Irisson based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Hervé CAPRA and 1 anonymous reviewer

Population dynamics and stock assessment models are only as good as the data used to parameterise them. For Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) populations, a critical parameter may be frequency of precocious maturation. Indeed, the young males (parrs) that mature early, before leaving the river to reach the ocean, can contribute to reproduction but have much lower survival rates afterwards. The authors cite evidence of the potentially major consequences of this alternate reproductive strategy. So, to be parameterised correctly, it needs to be assessed correctly. Cue the ultrasound machine. Through a thorough analysis of data collected on 850 individuals [1], over three years, the authors clearly show that the non-invasive examination of the internal cavity of young fishes to look for gonads, using a portable ultrasound machine, provides reliable and replicable evidence of precocious maturation. They turned into OB-GYN for salmons (albeit for male salmons!) and it worked. While using ultrasounds to detect fish gonads is not a new idea (early attempts for salmonids date back to the 80s [2]), the value here is in the comparison with the classic visual inspection technique (which turns out to be less reliable) and the fact that ultrasounds can now easily be carried out in the field. Beyond the potentially important consequences of this new technique for the correct assessment of salmon population dynamics, the authors also make the case for the acquisition of more reliable individual-level data in ecological studies, which I applaud. References. [1] Nevoux M, Marchand F, Forget G, Huteau D, Tremblay J, and Destouches J-P. (2019). Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging. bioRxiv 425561, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/425561 | Field assessment of precocious maturation in salmon parr using ultrasound imaging | Marie Nevoux, Frédéric Marchand, Guillaume Forget, Dominique Huteau, Julien Tremblay, Jean-Pierre Destouches | <p>Salmonids are characterized by a large diversity of life histories, but their study is often limited by the imperfect observation of the true state of an individual in the wild. Challenged by the need to reduce uncertainty of empirical data, re... | Conservation biology, Demography, Experimental ecology, Freshwater ecology, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology | Jean-Olivier Irisson | 2018-09-25 17:24:59 | View | ||

17 Mar 2021

Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslandsCatherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137Resolving herbivore influences under climate variabilityRecommended by Jennifer Krumins based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewersWe know that herbivory can have profound influences on plant communities with respect to their distribution and productivity (recently reviewed by Jia et al. 2018). However, the degree to which these effects are realized belowground in the rhizosphere is far less understood. Indeed, many independent studies and synthesis find that the environmental context can be more important than the direct effects of herbivore activity and its removal of plant biomass (Andriuzzi and Wall 2017, Schrama et al. 2013). In spite of dedicated attention, generalizable conclusions remain a bit elusive (Sitters and Venterink 2015). Picon-Cochard and colleagues (2021) help address this research conundrum in an elegant analysis that demonstrates the interaction between long-term cattle grazing and climatic variability on primary production aboveground and belowground. Over the course of two years, Picon-Cochard et al. (2021) measured above and belowground net primary productivity in French grasslands that had been subject to ten years of managed cattle grazing. When they compared these data with climatic trends, they find an interesting interaction among grazing intensity and climatic factors influencing plant growth. In short, and as expected, plants allocate more resources to root growth in dry years and more to above ground biomass in wet and cooler years. However, this study reveals the degree to which this is affected by cattle grazing. Grazed grasslands support warmer and dryer soils creating feedback that further and significantly promotes root growth over green biomass production. The implications of this work to understanding the capacity of grassland soils to store carbon is profound. This study addresses one brief moment in time of the long trajectory of this grazed ecosystem. The legacy of grazing does not appear to influence soil ecosystem functioning with respect to root growth except within the environmental context, in this case, climate. This supports the notion that long-term research in animal husbandry and grazing effects on landscapes is deeded. It is my hope that this study is one of many that can be used to synthesize many different data sets and build a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of grazing and herd management within the context of a changing climate. Herbivory has a profound influence upon ecosystem health and the distribution of plant communities (Speed and Austrheim 2017), global carbon storage (Chen and Frank 2020) and nutrient cycling (Sitters et al. 2020). The analysis and results presented by Picon-Cochard (2021) help to resolve the mechanisms that underly these complex effects and ultimately make projections for the future. References Andriuzzi WS, Wall DH. 2017. Responses of belowground communities to large aboveground herbivores: Meta‐analysis reveals biome‐dependent patterns and critical research gaps. Global Change Biology 23:3857-3868. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13675 Chen J, Frank DA. 2020. Herbivores stimulate respiration from labile and recalcitrant soil carbon pools in grasslands of Yellowstone National Park. Land Degradation & Development 31:2620-2634. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3656 Jia S, Wang X, Yuan Z, Lin F, Ye J, Hao Z, Luskin MS. 2018. Global signal of top-down control of terrestrial plant communities by herbivores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:6237-6242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707984115 Picon-Cochard C, Vassal N, Martin R, Herfurth D, Note P, Louault F. 2021. Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands. bioRxiv, 2020.08.23.263137, version 6 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.23.263137 Schrama M, Veen GC, Bakker EL, Ruifrok JL, Bakker JP, Olff H. 2013. An integrated perspective to explain nitrogen mineralization in grazed ecosystems. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15:32-44. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppees.2012.12.001 Sitters J, Venterink HO. 2015. The need for a novel integrative theory on feedbacks between herbivores, plants and soil nutrient cycling. Plant and Soil 396:421-426. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-015-2679-y Sitters J, Wubs EJ, Bakker ES, Crowther TW, Adler PB, Bagchi S, Bakker JD, Biederman L, Borer ET, Cleland EE. 2020. Nutrient availability controls the impact of mammalian herbivores on soil carbon and nitrogen pools in grasslands. Global Change Biology 26:2060-2071. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15023 Speed JD, Austrheim G. 2017. The importance of herbivore density and management as determinants of the distribution of rare plant species. Biological Conservation 205:77-84. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.030 | Intra and inter-annual climatic conditions have stronger effect than grazing intensity on root growth of permanent grasslands | Catherine Picon-Cochard, Nathalie Vassal, Raphaël Martin, Damien Herfurth, Priscilla Note, Frédérique Louault | <p>Background and Aims: Understanding how direct and indirect changes in climatic conditions, management, and species composition affect root production and root traits is of prime importance for the delivery of carbon sequestration services of gr... |  | Agroecology, Biodiversity, Botany, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning | Jennifer Krumins | 2020-08-30 19:27:30 | View | |

26 Mar 2019

Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity?Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_exploration.htmlProbing behaviors correlated with behavioral flexibilityRecommended by Jeremy Van Cleve based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Behavioral plasticity, which is a subset of phenotypic plasticity, is an important component of foraging, defense against predators, mating, and many other behaviors. More specifically, behavioral flexibility, in this study, captures how quickly individuals adapt to new circumstances. In cases where individuals disperse to new environments, which often occurs in range expansions, behavioral flexibility is likely crucial to the chance that individuals can establish in these environments. Thus, it is important to understand how best to measure behavioral flexibility and how measures of such flexibility might vary across individuals and behavioral contexts and with other measures of learning and problem solving. | Is behavioral flexibility linked with exploration, but not boldness, persistence, or motor diversity? | Kelsey McCune, Carolyn Rowney, Luisa Bergeron, Corina Logan | This is a PREREGISTRATION. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific file we are submitting is g_exploration.Rmd, which is easily accessible at GitHub at https://github.com/cor... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Jeremy Van Cleve | 2018-09-27 03:35:12 | View | ||

29 Mar 2021

Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variationRicardo A. Segovia https://doi.org/10.1101/836338New light on the baseline importance of temperature for the origin of geographic species richness gradientsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Rafael Molina-Venegas and 2 anonymous reviewers

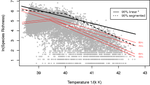

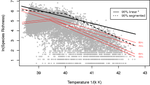

Whether environmental conditions –in particular energy and water availability– are sufficient to account for species richness gradients (e.g. Currie 1991), or the effects of other biotic and historical or regional factors need to be considered as well (e.g. Ricklefs 1987), was the subject of debate during the 1990s and 2000s (e.g. Francis & Currie 2003; Hawkins et al. 2003, 2006; Currie et al. 2004; Ricklefs 2004). The metabolic theory of ecology (Brown et al. 2004) provided a solid and well-rooted theoretical support for the preponderance of energy as the main driver for richness variations. As any good piece of theory, it provided testable predictions about the sign and shape (i.e. slope) of the relationship between temperature –a key aspect of ambient energy– and species richness. However, these predictions were not supported by empirical evaluations (e.g. Kreft & Jetz 2007; Algar et al. 2007; Hawkins et al. 2007a), as the effects of a myriad of other environmental gradients, regional factors and evolutionary processes result in a wide variety of richness–temperature responses across different groups and regions (Hawkins et al. 2007b; Hortal et al. 2008). So, in a textbook example of how good theoretical work helps advancing science even if proves to be (partially) wrong, the evaluation of this aspect of the metabolic theory of ecology led to current understanding that, while species richness does respond to current climatic conditions, many other ecological, evolutionary and historical factors do modify such response across scales (see, e.g., Ricklefs 2008; Hawkins 2008; D’Amen et al. 2017). And the kinetic model linking mean annual temperature and species richness (Allen et al. 2002; Brown et al. 2004) was put aside as being, perhaps, another piece of the puzzle of the origin of current diversity gradients. Segovia (2021) puts together an elegant way of reinvigorating this part of the metabolic theory of ecology. He uses quantile regressions to model just the upper parts of the relationship between species richness and mean annual temperature, rather than modelling its central tendency through the classical linear regression family of methods –as was done in the past. This assumes that the baseline effect of ambient energy does produce the negative linear relationship between richness and temperature predicted by the kinetic model (Allen et al. 2002), but also that this effect only poses an upper limit for species richness, and the effects of other factors may result in lower levels of species co-occurrence, thus producing a triangular rather than linear relationship. The results of Segovia’s simple and elegant analytical design show unequivocally that the predictions of the kinetic model become progressively more explanatory towards the upper quartiles of the relationship between species richness and temperature along over 10,000 tree local inventories throughout the Americas, reaching over 70% of explanatory power for the upper 5% of the relationship (i.e. the 95% quantile). This confirms to a large extent his reformulation of the predictions of the kinetic model. Further, the neat study from Segovia (2021) also provides evidence confirming that the well-known spatial non-stationarity in the richness–temperature relationship (see Cassemiro et al. 2007) also applies to its upper-bound segment. Both the explanatory power and the slope of the relationship in the 95% upper quantile vary widely between biomes, reaching values similar to the predictions of the kinetic model only in cold temperate environments –precisely where temperature becomes more important than water availability as a constrain to plant life (O’Brien 1998; Hawkins et al. 2003). Part of these variations are indeed related with changes in water deficit and number of frost days along the XXth Century, as shown by the residuals of this paper (Segovia 2021) and a more detailed separate study (Segovia et al. 2020). This pinpoints the importance of the relative balance between water and energy as two of the main climatic factors constraining species diversity gradients, confirming the value of hypotheses that date back to Humboldt’s work (see Hawkins 2001, 2008). There is however a significant amount of unexplained variation in Segovia’s analyses, in particular in the progressive departure of the predictions of the kinetic model as we move towards the tropics, or downwards along the lower quantiles of the richness–temperature relationship. This calls for a deeper exploration of the factors that modify the baseline relationship between richness and energy, opening a new avenue for the macroecological investigation of how different forces and processes shape up geographical diversity gradients beyond the mere energetic constrains imposed by the basal limitations of multicellular life on Earth. References Algar, A.C., Kerr, J.T. and Currie, D.J. (2007) A test of Metabolic Theory as the mechanism underlying broad-scale species-richness gradients. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 170-178. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2006.00275.x Allen, A.P., Brown, J.H. and Gillooly, J.F. (2002) Global biodiversity, biochemical kinetics, and the energetic-equivalence rule. Science, 297, 1545-1548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1072380 Brown, J.H., Gillooly, J.F., Allen, A.P., Savage, V.M. and West, G.B. (2004) Toward a metabolic theory of ecology. Ecology, 85, 1771-1789. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-9000 Cassemiro, F.A.d.S., Barreto, B.d.S., Rangel, T.F.L.V.B. and Diniz-Filho, J.A.F. (2007) Non-stationarity, diversity gradients and the metabolic theory of ecology. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 16, 820-822. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00332.x Currie, D.J. (1991) Energy and large-scale patterns of animal- and plant-species richness. The American Naturalist, 137, 27-49. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/285144 Currie, D.J., Mittelbach, G.G., Cornell, H.V., Field, R., Guegan, J.-F., Hawkins, B.A., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2004) Predictions and tests of climate-based hypotheses of broad-scale variation in taxonomic richness. Ecology Letters, 7, 1121-1134. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00671.x D'Amen, M., Rahbek, C., Zimmermann, N.E. and Guisan, A. (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169-187. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Francis, A.P. and Currie, D.J. (2003) A globally consistent richness-climate relationship for Angiosperms. American Naturalist, 161, 523-536. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/368223 Hawkins, B.A. (2001) Ecology's oldest pattern? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 16, 470. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02197-8 Hawkins, B.A. (2008) Recent progress toward understanding the global diversity gradient. IBS Newsletter, 6.1, 5-8. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8sr2k1dd Hawkins, B.A., Field, R., Cornell, H.V., Currie, D.J., Guégan, J.-F., Kaufman, D.M., Kerr, J.T., Mittelbach, G.G., Oberdorff, T., O'Brien, E., Porter, E.E. and Turner, J.R.G. (2003) Energy, water, and broad-scale geographic patterns of species richness. Ecology, 84, 3105-3117. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/03-8006 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Jaramillo, C.A. and Soeller, S.A. (2006) Post-Eocene climate change, niche conservatism, and the latitudinal diversity gradient of New World birds. Journal of Biogeography, 33, 770-780. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01452.x Hawkins, B.A., Albuquerque, F.S., Araújo, M.B., Beck, J., Bini, L.M., Cabrero-Sañudo, F.J., Castro Parga, I., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Ferrer-Castán, D., Field, R., Gómez, J.F., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Kitching, I.J., León-Cortés, J.L., et al. (2007a) A global evaluation of metabolic theory as an explanation for terrestrial species richness gradients. Ecology, 88, 1877-1888. doi:10.1890/06-1444.1. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-1444.1 Hawkins, B.A., Diniz-Filho, J.A.F., Bini, L.M., Araújo, M.B., Field, R., Hortal, J., Kerr, J.T., Rahbek, C., Rodríguez, M.Á. and Sanders, N.J. (2007b) Metabolic theory and diversity gradients: Where do we go from here? Ecology, 88, 1898–1902. doi: https://doi.org/10.1890/06-2141.1 Hortal, J., Rodríguez, J., Nieto-Díaz, M. and Lobo, J.M. (2008) Regional and environmental effects on the species richness of mammal assemblages. Journal of Biogeography, 35, 1202–1214. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2007.01850.x Kreft, H. and Jetz, W. (2007) Global patterns and determinants of vascular plant diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 104, 5925-5930. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608361104 O'Brien, E. (1998) Water-energy dynamics, climate, and prediction of woody plant species richness: an interim general model. Journal of Biogeography, 25, 379-398. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.252166.x Ricklefs, R.E. (1987) Community diversity: Relative roles of local and regional processes. Science, 235, 167-171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.235.4785.167 Ricklefs, R.E. (2004) A comprehensive framework for global patterns in biodiversity. Ecology Letters, 7, 1-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00554.x Ricklefs, R.E. (2008) Disintegration of the ecological community. American Naturalist, 172, 741-750. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/593002 Segovia, R.A. (2021) Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation. bioRxiv, 836338, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/836338 Segovia, R.A., Pennington, R.T., Baker, T.R., Coelho de Souza, F., Neves, D.M., Davis, C.C., Armesto, J.J., Olivera-Filho, A.T. and Dexter, K.G. (2020) Freezing and water availability structure the evolutionary diversity of trees across the Americas. Science Advances, 6, eaaz5373. doi: https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5373 | Temperature predicts the maximum tree-species richness and water and frost shape the residual variation | Ricardo A. Segovia | <p>The kinetic hypothesis of biodiversity proposes that temperature is the main driver of variation in species richness, given its exponential effect on biological activity and, potentially, on rates of diversification. However, limited support fo... |  | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Botany, Macroecology, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2019-11-10 20:56:40 | View | |

18 Dec 2020

Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islandsManuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.19.210880A meaningful application of species distribution models and functional traits to understand invasion dynamicsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey based on reviews by Paula Matos and Peter Convey

Polar and subpolar regions are fragile environments, where the introduction of alien species may completely change ecosystem dynamics if the alien species become keystone species (e.g. Croll, 2005). The increasing number of human visits, together with climate change, are favouring the introduction and settling of new invaders to these regions, particularly in Antarctica (Hughes et al. 2015). Within this context, the joint use of Species Distribution Models (SDM) –to assess the areas potentially suitable for the aliens– with other measures of the potential to become successful invaders can inform on the need for devoting specific efforts to eradicate these new species before they become naturalized (e.g. Pertierra et al. 2016). References Austin, M. P., Nicholls, A. O., and Margules, C. R. (1990). Measurement of the realized qualitative niche: environmental niches of five Eucalyptus species. Ecological Monographs, 60(2), 161-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1943043 | Once upon a time in the far south: Influence of local drivers and functional traits on plant invasion in the harsh sub-Antarctic islands | Manuele Bazzichetto, François Massol, Marta Carboni, Jonathan Lenoir, Jonas Johan Lembrechts, Rémi Joly, David Renault | <p>Aim Here, we aim to: (i) investigate the local effect of environmental and human-related factors on alien plant invasion in sub-Antarctic islands; (ii) explore the relationship between alien species features and their dependence on anthropogeni... |  | Biogeography, Biological invasions, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | 2020-07-21 21:13:08 | View | |

27 Apr 2021

Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit fliesBenoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326Understanding the interplay between host-specificity, environmental conditions and competition through the sound application of Joint Species Distribution ModelsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann based on reviews by Joaquín Calatayud and Carsten Dormann

Understanding why and how species coexist in local communities is one of the central questions in ecology. There is general agreement that species distribution and coexistence are determined by a number of key mechanisms, including the environmental requirements of species, dispersal, evolutionary constraints, resource availability and selection, metapopulation dynamics, and biotic interactions (e.g. Soberón & Nakamura 2009; Colwell & Rangel 2009; Ricklefs 2015). These factors are however intricately intertwined in a scale-structured fashion (Hortal et al. 2010; D’Amen et al. 2017), making it particularly difficult to tease apart the effects of each one of them. This could be addressed by the novel field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling (JSDM; Okasvainen & Abrego 2020), as it allows assessing the effects of several sets of factors and the co-occurrence and/or covariation in abundances of potentially interacting species at the same time (Pollock et al. 2014; Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Dormann et al. 2018). However, the development of JSDM has been hampered by the general lack of good-quality detailed data on species co-occurrences and abundances (see Hortal et al. 2015). Facon et al. (2021) use a particularly large compilation of field surveys to study the abundance and co-occurrence of Tephritidae fruit flies in c. 400 orchards, gardens and natural areas throughout the island of Réunion. Further, they combine such information with lab data on their host-selection fundamental niche (i.e. in the absence of competitors), codifying traits of female choice and larval performances in 21 host species. They use Poisson Log-Normal models, a type of mixed model that allows one to jointly model the random effects associated with all species, and retrieve the covariations in abundance that are not explained by environmental conditions or differences in sampling effort. Then, they use a series of models to evaluate the effects on these matrices of ecological covariates (date, elevation, habitat, climate and host plant), species interactions (by comparing with a constrained residual variance-covariance matrix) and the species’ host-selection fundamental niches (through separate models for each fly species). The eight Tephritidae species inhabiting Réunion include both generalists and specialists in Solanaceae and Cucurbitaceae with a known history of interspecific competition. Facon et al. (2021) use a comprehensive JSDM approach to assess the effects of different factors separately and altogether. This allows them to identify large effects of plant hosts and the fundamental host-selection niche on species co-occurrence, but also to show that ecological covariates and weak –though not negligible– species interactions are necessary to account for all residual variance in the matrix of joint species abundances per site. Further, they also find evidence that the fitness per host measured in the lab has a strong influence on the abundances in each host plant in the field for specialist species, but not for generalists. Indeed, the stronger effects of competitive exclusion were found in pairs of Cucurbitaceae specialist species. However, these analyses fail to provide solid grounds to assess why generalists are rarely found in Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae. Although they argue that this may be due to Connell’s (1980) ghost of competition past (past competition that led to current niche differentiation), further data on the evolutionary history of these fruit flies is needed to assess this hypothesis. Finding evidence for the effects of competitive interactions on species’ occurrences and spatial distributions is often difficult, perhaps because these effects occur over longer time scales than the ones usually studied by ecologists (Yackulic 2017). The work by Facon and colleagues shows that weak effects of competition can be detected also at the short ecological timescales that determine coexistence in local communities, under the virtuous combination of good-quality data and sound analytical designs that account for several aspects of species’ niches, their biotopes and their joint population responses. This adds a new dimension to the application of Hutchinson’s (1978) niche framework to understand the spatial dynamics of species and communities (see also Colwell & Rangel 2009), although further advances to incorporate dispersal-driven metacommunity dynamics (see, e.g., Ovaskainen et al. 2016; Leibold et al. 2017) are certainly needed. Nonetheless, this work shows the potential value of in-depth analyses of species coexistence based on combining good-quality field data with well-thought out JSDM applications. If many studies like this are conducted, it is likely that the uprising field of Joint Species Distribution Modelling will improve our understanding of the hierarchical relationships between the different factors affecting species coexistence in ecological communities in the near future.

References Colwell RK, Rangel TF (2009) Hutchinson’s duality: The once and future niche. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19651–19658. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901650106 Connell JH (1980) Diversity and the Coevolution of Competitors, or the Ghost of Competition Past. Oikos, 35, 131–138. https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 D’Amen M, Rahbek C, Zimmermann NE, Guisan A (2017) Spatial predictions at the community level: from current approaches to future frameworks. Biological Reviews, 92, 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12222 Dormann CF, Bobrowski M, Dehling DM, Harris DJ, Hartig F, Lischke H, Moretti MD, Pagel J, Pinkert S, Schleuning M, Schmidt SI, Sheppard CS, Steinbauer MJ, Zeuss D, Kraan C (2018) Biotic interactions in species distribution modelling: 10 questions to guide interpretation and avoid false conclusions. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 27, 1004–1016. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12759 Facon B, Hafsi A, Masselière MC de la, Robin S, Massol F, Dubart M, Chiquet J, Frago E, Chiroleu F, Duyck P-F, Ravigné V (2021) Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of community structure in fruit flies. bioRxiv, 2020.12.07.414326. ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.07.414326 Hortal J, de Bello F, Diniz-Filho JAF, Lewinsohn TM, Lobo JM, Ladle RJ (2015) Seven Shortfalls that Beset Large-Scale Knowledge of Biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 46, 523–549. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054400 Hortal J, Roura‐Pascual N, Sanders NJ, Rahbek C (2010) Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 33, 51–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06428.x Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Leibold MA, Chase JM, Ernest SKM (2017) Community assembly and the functioning of ecosystems: how metacommunity processes alter ecosystems attributes. Ecology, 98, 909–919. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.1697 Ovaskainen O, Abrego N (2020) Joint Species Distribution Modelling: With Applications in R. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108591720 Ovaskainen O, Roy DB, Fox R, Anderson BJ (2016) Uncovering hidden spatial structure in species communities with spatially explicit joint species distribution models. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12502 Pollock LJ, Tingley R, Morris WK, Golding N, O’Hara RB, Parris KM, Vesk PA, McCarthy MA (2014) Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM). Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 397–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180 Ricklefs RE (2015) Intrinsic dynamics of the regional community. Ecology Letters, 18, 497–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12431 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Yackulic CB (2017) Competitive exclusion over broad spatial extents is a slow process: evidence and implications for species distribution modeling. Ecography, 40, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02836 | Joint species distributions reveal the combined effects of host plants, abiotic factors and species competition as drivers of species abundances in fruit flies | Benoit Facon, Abir Hafsi, Maud Charlery de la Masselière, Stéphane Robin, François Massol, Maxime Dubart, Julien Chiquet, Enric Frago, Frédéric Chiroleu, Pierre-François Duyck & Virginie Ravigné | <p style="text-align: justify;">The relative importance of ecological factors and species interactions for phytophagous insect species distributions has long been a controversial issue. Using field abundances of eight sympatric Tephritid fruit fli... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Herbivory, Interaction networks, Species distributions | Joaquín Hortal | Carsten Dormann, Joaquín Calatayud | 2020-12-08 06:44:25 | View |

16 Jun 2023

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansionThibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environmentsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

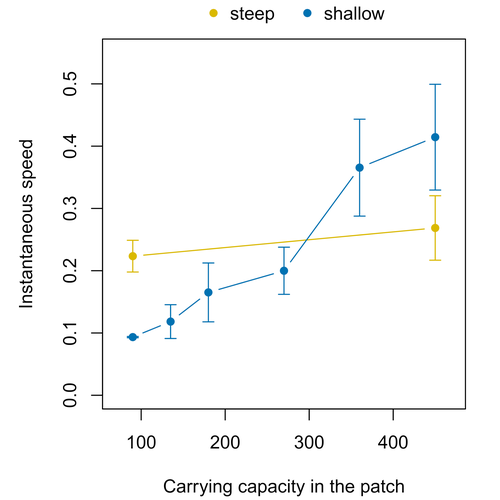

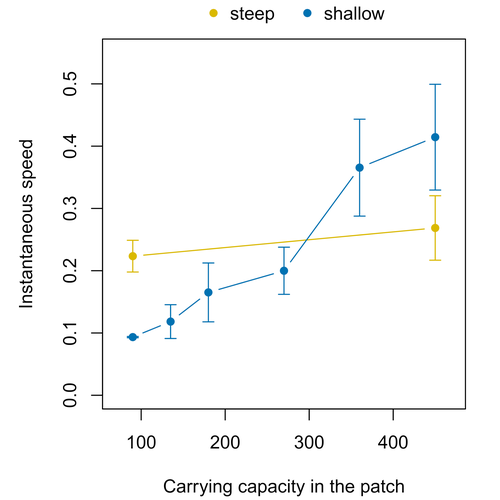

Dispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007). Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients). Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011). The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions. REFERENCES Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746 Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1 Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431. Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255 Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107 Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x | Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion | Thibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken | <p>Demographic processes that occur at the local level, such as positive density dependence in growth or dispersal, are known to shape population range expansion, notably by linking carrying capacity to invasion speed. As a result of these process... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Joaquín Hortal | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-11-16 15:52:08 | View |

25 Nov 2022

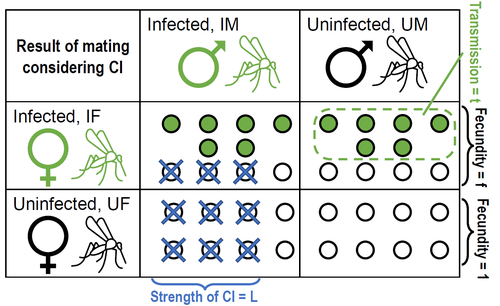

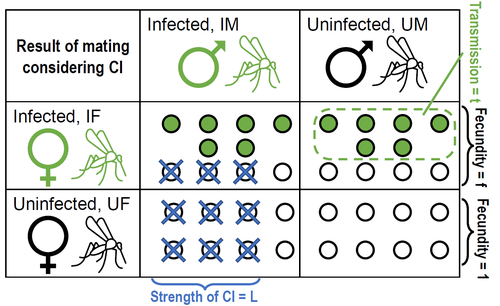

Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populationsPetteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824Population dynamics of Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll and Mr. HydeRecommended by Jorge Peña based on reviews by 3 anonymous reviewers"Good and evil are so close as to be chained together in the soul" Maternally inherited symbionts—microorganisms that pass from a female host to her progeny—have two main ways of increasing their own fitness. First, they can increase the fecundity or viability of infected females. This “positive fitness effects” strategy is the one commonly used by mutualistic symbionts, such as Buchnera aphidicola—the bacterial endosymbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum [4]. Second, maternally inherited symbionts can manipulate the reproduction of infected females in a way that enhances symbiont transmission at the expense of host fitness. A famous example of this “reproductive parasitism” strategy is the cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) [3] induced by bacteria of the genus Wolbachia in their arthropod and nematode hosts. CI works as a toxin-antidote system, whereby the sperm of infected males is modified in a lethal way (toxin) that can only be reverted if the egg is also infected (antidote) [1]. As a result, CI imposes a kind of conditional sterility on their hosts: while infected females are compatible with both infected and uninfected males, uninfected females experience high offspring mortality if (and only if) they mate with infected males [7]. These two symbiont strategies (positive fitness effects versus reproductive parasitism) have been traditionally studied separately, both empirically and theoretically. However, it has become clear that the two strategies are not mutually exclusive, and that a reproductive parasite can simultaneously act as a mutualist—an infection type that has been dubbed “Jekyll and Hyde” [6], after the famous novella by Robert Louis Stevenson about kind scientist Dr. Jekyll and his evil alter ego, Mr. Hyde. In important previous work, Zug and Hammerstein [7] analyzed the consequences of positive fitness effects on the dynamics of different kind of infections, including “Jekyll and Hyde” infections characterized by CI and other reproductive parasitism strategies. Building on this and related modeling framework, Karisto et al. [2] re-investigate and expand on the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism in Wolbachia infections by focusing on CI in both diplodiploid and haplodiploid populations, and by paying particular attention to the mathematical assumption structure underlying their results. Karisto et al. begin by reviewing classic models of Wolbachia infections in diplodiploid populations that assume a “negative fitness effect” (modeled as a fertility penalty on infected females), characteristic of a pure strategy of reproductive parasitism. Together with the positive frequency-dependent effects due to CI (whereby the fitness benefits to symbionts infecting females increase with the proportion of infected males in the population) this results in population dynamics characterized by two stable equilibria (the Wolbachia-free state and an interior equilibrium with a high frequency of Wolbachia-carrying hosts) separated by an unstable interior equilibrium. Wolbachia can then spread once the initial frequency is above a threshold or an invasion barrier, but is prevented from fixing by a proportion of infections failing to be passed on to offspring. Karisto et al. show that, given the assumption of negative fitness effects, the stable interior equilibrium can never feature a Wolbachia prevalence below one-half. Moreover, they convincingly argue that a prevalence greater than but close to one-half is difficult to maintain in the presence of stochastic fluctuations, as in these cases the high-prevalence stable equilibrium would be too close to the unstable equilibrium signposting the invasion barrier. Karisto et al. then relax the assumption of negative fitness effects and allow for positive fitness effects (modeled as a fertility premium on infected females) in a diplodiploid population. They show that positive fitness effects may result in situations where the original invasion threshold is now absent, the bistable coexistence dynamics are transformed into purely co-existence dynamics, and Wolbachia symbionts can now invade when rare. Karisto et al. conclude that positive fitness effects provide a plausible and potentially testable explanation for the low frequencies of symbiont-carrying hosts that are sometimes observed in nature, which are difficult to reconcile with the assumption of negative fitness effects. Finally, Karisto et al. extend their analysis to haplodiploid host populations (where all fertilized eggs develop as females). Here, they investigate two types of cytoplasmic incompatibility: a female-killing effect, similar to the CI effect studied in diplodiploid populations (the “Leptopilina type” of Vavre et al. [5]) and a masculinization effect, where CI leads to the loss of paternal chromosomes and to the development of the offspring as a male (the “Nasonia type” of Vavre et al. [5]). The models are now two-sex, which precludes a complete analytical treatment, in particular regarding the stability of fixed points. Karisto et al. compensate by conducting large numerical analyses that support their claims. Importantly, all main conclusions regarding the interplay between positive fitness effects and reproductive parasitism continue to hold under haplodiploidy. All in all, the analysis and results by Karisto et al. suggest that it is not necessary to resort to classical (but depending on the situation, unlikely) mechanisms, such as ongoing invasion or source-sink dynamics, to explain arthropod populations featuring low-prevalent Wolbachia infections. Instead, low-frequency equilibria might be simply due to reproductive parasites conferring beneficial fitness effects, or Wolbachia symbionts playing Dr. Jekyll (positive fitness effects) and Mr. Hyde (cytoplasmatic incompatibility). References [1] Beckmann JF, Bonneau M, Chen H, Hochstrasser M, Poinsot D, Merçot H, Weill M, Sicard M, Charlat S (2019) The Toxin–Antidote Model of Cytoplasmic Incompatibility: Genetics and Evolutionary Implications. Trends in Genetics, 35, 175–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2018.12.004 [2] Karisto P, Duplouy A, Vries C de, Kokko H (2022) Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations. bioRxiv, 2022.04.11.487824, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.11.487824 [3] Laven H (1956) Cytoplasmic Inheritance in Culex. Nature, 177, 141–142. https://doi.org/10.1038/177141a0 [4] Perreau J, Zhang B, Maeda GP, Kirkpatrick M, Moran NA (2021) Strong within-host selection in a maternally inherited obligate symbiont: Buchnera and aphids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118, e2102467118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2102467118 [5] Vavre F, Fleury F, Varaldi J, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M (2000) Evidence for Female Mortality in Wolbachia-Mediated Cytoplasmic Incompatibility in Haplodiploid Insects: Epidemiologic and Evolutionary Consequences. Evolution, 54, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00019.x [6] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2015) Bad guys turned nice? A critical assessment of Wolbachia mutualisms in arthropod hosts. Biological Reviews, 90, 89–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12098 [7] Zug R, Hammerstein P (2018) Evolution of reproductive parasites with direct fitness benefits. Heredity, 120, 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41437-017-0022-5 | Positive fitness effects help explain the broad range of Wolbachia prevalences in natural populations | Petteri Karisto, Anne Duplouy, Charlotte de Vries, Hanna Kokko | <p style="text-align: justify;">The bacterial endosymbiont <em>Wolbachia</em> is best known for its ability to modify its host’s reproduction by inducing cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) to facilitate its own spread. Classical models predict eithe... |  | Host-parasite interactions, Population ecology | Jorge Peña | 2022-04-12 12:52:55 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle