Direct submissions to PCI Ecology from bioRxiv.org are possible using the B2J service

Latest recommendations

| Id | Title * | Authors * | Abstract * | Picture * | Thematic fields * | Recommender▲ | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View | ||

26 Apr 2021

Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in EuropeOlvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dpA planned experiment on local adaptation in a host-parasite system: is adaptation to the host linked to its recent domestication?Recommended by Eric Petit based on reviews by Sharon Zytynska, Alex Stemmelen and 1 anonymous reviewerLocal adaptation shall occur whenever selective pressures vary across space and overwhelm the effects of gene flow and local extinctions (Kawecki and Ebert 2004). Because the intimate interaction that characterizes their relationship exerts a strong selective pressure on both partners, host-parasite systems represent a classical example in which local adaptation is expected from rapidly evolving parasites adapting to more evolutionary constrained hosts (Kaltz and Shykoff 1998). Such systems indeed represent a large proportion of the study-cases in local adaptation research (Runquist et al. 2020). Biotic interactions intervene in many environment-related societal challenges, so that understanding when and how local adaptation arises is important not only for understanding evolutionary dynamics but also for more applied questions such as the control of agricultural pests, biological invasions, or pathogens (Parker and Gilbert 2004). The exact conditions under which local adaptation does occur and can be detected is however still the focus of many theoretical, methodological and empirical studies (Blanquart et al. 2013, Hargreaves et al. 2020, Hoeksema and Forde 2008, Nuismer and Gandon 2008, Richardson et al. 2014). A recent review that evaluates investigations that examined the combined influence of biotic and abiotic factors on local adaptation reaches partial conclusions about their relative importance in different contexts and underlines the many traps that one has to avoid in such studies (Runquist et al. 2020). The authors of this review emphasize that one should evaluate local adaptation using wild-collected strains or populations and over multiple generations, on environmental gradients that span natural ranges of variation for both biotic and abiotic factors, in a theory-based hypothetico-deductive framework that helps interpret the outcome of experiments. These multiple targets are not easy to reach in each local adaptation experiment given the diversity of systems in which local adaptation may occur. Improving research practices may also help better understand when and where local adaptation does occur by adding controls over p-hacking, HARKing or publication bias, which is best achieved when hypotheses, date collection and analytical procedures are known before the research begins (Chambers et al. 2014). In this regard, the route taken by Olvera-Vazquez et al. (2021) is interesting. They propose to investigate whether the rosy aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) recently adapted to its cultivated host, the apple tree (Malus domestica), and chose to pre-register their hypotheses and planned experiments on PCI Ecology (Peer Community In 2020). Though not fulfilling all criteria mentioned by Runquist et al. (2020), they clearly state five hypotheses that all relate to the local adaptation of this agricultural pest to an economically important fruit tree, and describe in details a powerful, randomized experiment, including how data will be collected and analyzed. The experimental set-up includes comparisons between three sites located along a temperature transect that also differ in local edaphic and biotic factors, and contrasts wild and domesticated apple trees that originate from the three sites and were both planted in the local, sympatric site, and transplanted to allopatric sites. Beyond enhancing our knowledge on local adaptation, this experiment will also test the general hypothesis that the rosy aphid recently adapted to Malus sp. after its domestication, a question that population genetic analyses was not able to answer (Olvera-Vazquez et al. 2020). References Blanquart F, Kaltz O, Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2013) A practical guide to measuring local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 16, 1195–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12150 Briscoe Runquist RD, Gorton AJ, Yoder JB, Deacon NJ, Grossman JJ, Kothari S, Lyons MP, Sheth SN, Tiffin P, Moeller DA (2019) Context Dependence of Local Adaptation to Abiotic and Biotic Environments: A Quantitative and Qualitative Synthesis. The American Naturalist, 195, 412–431. https://doi.org/10.1086/707322 Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ, Chambers CD, Feredoes E, Muthukumaraswamy SD, Etchells PJ (2014) Instead of “playing the game” it is time to change the rules: Registered Reports at <em>AIMS Neuroscience</em> and beyond. AIMS Neuroscience, 1, 4–17. https://doi.org/10.3934/Neuroscience.2014.1.4 Hargreaves AL, Germain RM, Bontrager M, Persi J, Angert AL (2019) Local Adaptation to Biotic Interactions: A Meta-analysis across Latitudes. The American Naturalist, 195, 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1086/707323 Hoeksema JD, Forde SE (2008) A Meta‐Analysis of Factors Affecting Local Adaptation between Interacting Species. The American Naturalist, 171, 275–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/527496 Kaltz O, Shykoff JA (1998) Local adaptation in host–parasite systems. Heredity, 81, 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.1998.00435.x Kawecki TJ, Ebert D (2004) Conceptual issues in local adaptation. Ecology Letters, 7, 1225–1241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00684.x Nuismer SL, Gandon S (2008) Moving beyond Common‐Garden and Transplant Designs: Insight into the Causes of Local Adaptation in Species Interactions. The American Naturalist, 171, 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1086/587077 Olvera-Vazquez SG, Remoué C, Venon A, Rousselet A, Grandcolas O, Azrine M, Momont L, Galan M, Benoit L, David G, Alhmedi A, Beliën T, Alins G, Franck P, Haddioui A, Jacobsen SK, Andreev R, Simon S, Sigsgaard L, Guibert E, Tournant L, Gazel F, Mody K, Khachtib Y, Roman A, Ursu TM, Zakharov IA, Belcram H, Harry M, Roth M, Simon JC, Oram S, Ricard JM, Agnello A, Beers EH, Engelman J, Balti I, Salhi-Hannachi A, Zhang H, Tu H, Mottet C, Barrès B, Degrave A, Razmjou J, Giraud T, Falque M, Dapena E, Miñarro M, Jardillier L, Deschamps P, Jousselin E, Cornille A (2020) Large-scale geographic survey provides insights into the colonization history of a major aphid pest on its cultivated apple host in Europe, North America and North Africa. bioRxiv, 2020.12.11.421644. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.11.421644 Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T., Dapena E., Lemarquand A. and Cornille A. (2021) Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) to its host (Malus domestica) and to its climate in Europe. In principle recommendation by Peer Community In Ecology. https://forgemia.inra.fr/amandine.cornille/local_adaptation_dp, ver. 4. Parker IM, Gilbert GS (2004) The Evolutionary Ecology of Novel Plant-Pathogen Interactions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 35, 675–700. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132339 Peer Community In. (2020, January 15). Submit your preregistration to Peer Community In for peer review. https://peercommunityin.org/2020/01/15/submit-your-preregistration-to-peer-community-in-for-peer-review/ Richardson JL, Urban MC, Bolnick DI, Skelly DK (2014) Microgeographic adaptation and the spatial scale of evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 29, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.01.002 | Experimental test for local adaptation of the rosy apple aphid (Dysaphis plantaginea) during its recent rapid colonization on its cultivated apple host (Malus domestica) in Europe | Olvera-Vazquez S.G., Alhmedi A., Miñarro M., Shykoff J. A., Marchadier E., Rousselet A., Remoué C., Gardet R., Degrave A. , Robert P. , Chen X., Porcher J., Giraud T., Vander-Mijnsbrugge K., Raffoux X., Falque M., Alins, G., Didelot F., Beliën T.,... | <p style="text-align: justify;">Understanding the extent of local adaptation in natural populations and the mechanisms enabling populations to adapt to their environment is a major avenue in ecology research. Host-parasite interaction is widely se... | Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations | Eric Petit | 2020-07-26 18:31:42 | View | ||

05 Mar 2019

Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at inhibition?Corina Logan, Kelsey McCune, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Claudia Wascher http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_inhibition.htmlAdapting to a changing environment: advancing our understanding of the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibilityRecommended by Erin Vogel based on reviews by Simon Gingins and 2 anonymous reviewersBehavioral flexibility is essential for organisms to adapt to an ever-changing environment. However, the mechanisms that lead to behavioral flexibility and understanding what traits makes a species better able to adapt behavior to new environments has been understudied. Logan and colleagues have proposed to use a series of experiments, using great-tailed grackles as a study species, to test four main hypotheses. These hypotheses are centered around exploring the relationship between behavioral flexibility and inhibition in grackles. This current preregistration is a part of a larger integrative research plan examining behavioral flexibility when faced with environmental change. In this part of the project they will examine specifically if individuals that are more flexible are also better at inhibiting: in other words: they will test the assumption that inhibition is required for flexibility. | Are the more flexible great-tailed grackles also better at inhibition? | Corina Logan, Kelsey McCune, Zoe Johnson-Ulrich, Luisa Bergeron, Carolyn Rowney, Benjamin Seitz, Aaron Blaisdell, Claudia Wascher | This is a PREREGISTRATION. The DOI was issued by OSF and refers to the whole GitHub repository, which contains multiple files. The specific file we are submitting is g_inhibition.Rmd, which is easily accessible at GitHub at https://github.com/cori... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Erin Vogel | 2018-10-12 18:36:00 | View | ||

06 Oct 2020

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.htmlThe role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansionRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Pizza Ka Yee Chow, Tim Parker and 1 anonymous reviewer

Understanding the relative importance of species-specific traits and environmental factors in modulating species distributions is an intriguing question in ecology [1]. Both behavioral flexibility (i.e., the ability to change the behavior in changing circumstances) and habitat availability are known to influence the ability of a species to expand its geographic range [2,3]. However, the role of each factor is context and species dependent and more information is needed to understand how these two factors interact. In this pre-registration, Logan et al. [4] explain how they will use Great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus), a species with a flexible behavior and a rapid geographic range expansion, to evaluate the relative role of habitat and behavior as drivers of the species’ expansion [4]. The authors present very clear hypotheses, predicted results and also include alternative predictions. The rationales for all the hypotheses are clearly stated, and the methodology (data and analyses plans) are described with detail. The large amount of information already collected by the authors for the studied species during previous projects warrants the success of this study. It is also remarkable that the authors will make all their data available in a public repository, and that the pre-registration in already stored in GitHub, supporting open access and reproducible science. I agree with the three reviewers of this pre-registration about its value and I think its quality has largely improved during the review process. Thus, I am happy to recommend it and I am looking forward to seeing the results. References [1] Gaston KJ. 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges. Oxford series in Ecology and Evolution. Oxford University Press, New York. [2] Sol D, Lefebvre L. 2000. Behavioural flexibility predicts invasion success in birds introduced to new zealand. Oikos. 90(3): 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.900317.x [3] Hanski I, Gilpin M. 1991. Metapopulation dynamics: Brief history and conceptual domain. Biological journal of the Linnean Society. 42(1-2): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00548.x [4] Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D. 2020. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes (http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html) In principle acceptance by PCI Ecology of the version on 16 Dec 2021 https://github.com/corinalogan/grackles/blob/0fb956040a34986902a384a1d8355de65010effd/Files/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.Rmd. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of a species to rapidly expand their geographic range (e.g., Lefebvre et al. (1997), Griffin a... | Behaviour & Ethology, Biological invasions, Dispersal & Migration, Foraging, Habitat selection, Human impact, Phenotypic plasticity, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | Anonymous, Caroline Marie Jeanne Yvonne Nieberding, Tim Parker | 2020-05-14 11:18:57 | View | |

03 Feb 2023

The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pairJeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879peDrivers of range expansion in a pair of sister grackle speciesRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

The spatial distribution of a species is driven by both biotic and abiotic factors that may change over time (Soberón & Nakamura, 2009; Paquette & Hargreaves, 2021). Therefore, species ranges are dynamic, especially in humanized landscapes where changes occur at high speeds (Sirén & Morelli, 2020). The distribution of many species is being reduced because of human impacts; however, some species are expanding their distributions, even over their niche (Lustenhouwer & Parker, 2022). One of the factors that may lead to a geographic niche expansion is behavioral flexibility (Mikhalevich et al., 2017), but the mechanisms determining range expansion through behavioral changes are not fully understood. The PCI Ecology study by Summers et al. (2023) uses a very large database on the current and historic distribution of two species of grackles that have shown different trends in their distribution. The great-tailed grackle has largely expanded its range over the 20th century, while the range of the boat-tailed grackle has remained very similar. They take advantage of this differential response in the distribution of the two species and run several analyses to test whether it was a change in habitat availability, in the realized niche, in habitat connectivity or in in the other traits or conditions that previously limited the species range, what is driving the observed distribution of the species. The study finds a change in the niche of great-tailed grackle, consistent with the high behavioral flexibility of the species. The two reviewers and I have seen a lot of value in this study because 1) it addresses a very timely question, especially in the current changing world; 2) it is a first step to better understanding if behavioral attributes may affect species’ ability to change their niche; 3) it contrasts the results using several complementary statistical analyses, reinforcing their conclusions; 4) it is based on the preregistration Logan et al (2021), and any deviations from it are carefully explained and justified in the text and 5) the limitations of the study have been carefully discussed. It remains to know if the boat-tailed grackle has more limited behavioral flexibility than the great-tailed grackle, further confirming the results of this study. Logan CJ, McCune KB, Chen N, Lukas D (2021) Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior and habitat changes. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/gxpopbehaviorhabitat.html Lustenhouwer N, Parker IM (2022) Beyond tracking climate: Niche shifts during native range expansion and their implications for novel invasions. Journal of Biogeography, 49, 1481–1493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14395 Mikhalevich I, Powell R, Logan C (2017) Is behavioural flexibility evidence of cognitive complexity? How evolution can inform comparative cognition. Interface Focus, 7, 20160121. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2016.0121 Paquette A, Hargreaves AL (2021) Biotic interactions are more often important at species’ warm versus cool range edges. Ecology Letters, 24, 2427–2438. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13864 Sirén APK, Morelli TL (2020) Interactive range-limit theory (iRLT): An extension for predicting range shifts. Journal of Animal Ecology, 89, 940–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13150 Soberón J, Nakamura M (2009) Niches and distributional areas: Concepts, methods, and assumptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 19644–19650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0901637106 Summers JT, Lukas D, Logan CJ, Chen N (2022) The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/879pe | The role of climate change and niche shifts in divergent range dynamics of a sister-species pair | Jeremy Summers, Dieter Lukas, Corina J. Logan, Nancy Chen | <p>---This is a POST-STUDY manuscript for the PREREGISTRATION, which received in principle acceptance in 2020 from Dr. Sebastián González (reviewed by Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow; <a href="https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ec... |  | Behaviour & Ethology, Biogeography, Dispersal & Migration, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Preregistrations, Species distributions | Esther Sebastián González | 2022-05-26 20:07:33 | View | |

28 Aug 2023

Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changesLogan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30JBehavioral changes in the rapid geographic expansion of the great-tailed grackleRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Pizza Ka Yee Chow and 1 anonymous reviewer

While many species' populations are declining, primarily due to human-related impacts (McKnee et al., 2014), certain species have thrived by utilizing human-influenced environments, leading to their population expansion (Muñoz & Real, 2006). In this context, the capacity to adapt and modify behaviors in response to new surroundings is believed to play a crucial role in facilitating species' spread to novel areas (Duckworth & Badyaev, 2007). For example, an increase in innovative behaviors within recently established communities could aid in discovering previously untapped food resources, while a decrease in exploration might reduce the likelihood of encountering dangers in unfamiliar territories (e.g., Griffin et al., 2016). To investigate the contribution of these behaviors to rapid range expansions, it is essential to directly measure and compare behaviors in various populations of the species. The study conducted by Logan et al. (2023) aims to comprehend the role of behavioral changes in the range expansion of great-tailed grackles (Quiscalus mexicanus). To achieve this, the researchers compared the prevalence of specific behaviors at both the expansion's edge and its middle. Great-tailed grackles were chosen as an excellent model due to their behavioral adaptability, rapid geographic expansion, and their association with human-modified environments. The authors carried out a series of experiments in captivity using wild-caught individuals, following a detailed protocol. The study successfully identified differences in two of the studied behavioral traits: persistence (individuals participated in a larger proportion of trials) and flexibility variance (a component of the species' behavioral flexibility, indicating a higher chance that at least some individuals in the population could be more flexible). Notably, individuals at the edge of the population exhibited higher values of persistence and flexibility, suggesting that these behavioral traits might be contributing factors to the species' expansion. Overall, the study by Logan et al. (2023) is an excellent example of the importance of behavioral flexibility and other related behaviors in the process of species' range expansion and the significance of studying these behaviors across different populations to gain a better understanding of their role in the expansion process. Finally, it is important to underline that this study is part of a pre-registration that received an In Principle Recommendation in PCI Ecology (Sebastián-González 2020) where objectives, methodology, and expected results were described in detail. The authors have identified any deviation from the original pre-registration and thoroughly explained the reasons for their deviations, which were very clear. References Duckworth, R. A., & Badyaev, A. V. (2007). Coupling of dispersal and aggression facilitates the rapid range expansion of a passerine bird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104(38), 15017-15022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706174104 Griffin, A.S., Guez, D., Federspiel, I., Diquelou, M., Lermite, F. (2016). Invading new environments: A mechanistic framework linking motor diversity and cognition to establishment success. Biological Invasions and Animal Behaviour, 26e46. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139939492.004 Logan, C. J., McCune, K., LeGrande-Rolls, C., Marfori, Z., Hubbard, J., Lukas, D. 2023. Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2N30J McKee, J. K., Sciulli, P. W., Fooce, C. D., & Waite, T. A. (2004). Forecasting global biodiversity threats associated with human population growth. Biological Conservation, 115(1), 161-164. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(03)00099-5 Muñoz, A. R., & Real, R. (2006). Assessing the potential range expansion of the exotic monk parakeet in Spain. Diversity and Distributions, 12(6), 656-665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2006.00272.x Sebastián González, E. (2020) The role of behavior and habitat availability on species geographic expansion. Peer Community in Ecology, 100062. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100062. Reviewers: Caroline Nieberding, Tim Parker, and Pizza Ka Yee Chow. | Implementing a rapid geographic range expansion - the role of behavior changes | Logan CJ, McCune KB, LeGrande-Rolls C, Marfori Z, Hubbard J, Lukas D | <p>It is generally thought that behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change, plays an important role in the ability of species to rapidly expand their geographic range. Great-tailed grackles (<em>Quiscalus mexi... | Behaviour & Ethology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Esther Sebastián González | 2023-04-12 11:00:42 | View | ||

18 Apr 2024

Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its preyMellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.08.566247Unveiling the influence of carrion pulses on predator-prey dynamicsRecommended by Esther Sebastián González based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Eli Strauss and 1 anonymous reviewer

Most, if not all, predators consume carrion in some circumstances (Sebastián-Gonzalez et al. 2023). Consequently, significant fluctuations in carrion availability can impact predator-prey dynamics by altering the ratio of carrion to live prey in the predators' diet (Roth 2003). Changes in carrion availability may lead to reduced predation when carrion is more abundant (hypo-predation) and intensified predation if predator populations surge in response to carrion influxes but subsequently face scarcity (hyper-predation), (Moleón et al. 2014, Mellard et al. 2021). However, this relationship between predation and scavenging is often challenging because of the lack of empirical data. | Insights on the effect of mega-carcass abundance on the population dynamics of a facultative scavenger predator and its prey | Mellina Sidous; Sarah Cubaynes; Olivier Gimenez; Nolwenn Drouet-Hoguet; Stephane Dray; Loic Bollache; Daphine Madhlamoto; Nobesuthu Adelaide Ngwenya; Herve Fritz; Marion Valeix | <p>The interplay between facultative scavenging and predation has gained interest in the last decade. The prevalence of scavenging induced by the availability of large carcasses may modify predator density or behaviour, potentially affecting prey.... |  | Community ecology | Esther Sebastián González | Eli Strauss | 2023-11-14 15:27:16 | View |

30 Sep 2020

How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessmentFlorence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.02.129536Citizen science contributes to SDM validationRecommended by Francisco Lloret based on reviews by Maria Angeles Perez-Navarro and 1 anonymous reviewerCitizen science is becoming an important piece for the acquisition of scientific knowledge in the fields of natural sciences, and particularly in the inventory and monitoring of biodiversity (McKinley et al. 2017). The information generated with the collaboration of citizens has an evident importance in conservation, by providing information on the state of populations and habitats, helping in mitigation and restoration actions, and very importantly contributing to involve society in conservation (Brown and Williams 2019).

An obvious advantage of these initiatives is the ability to mobilize human resources on a large territorial scale and in the medium term, which would otherwise be difficult to finance. The resulting increasing information then can be processed with advanced computational techniques (Hochachka et al 2012; Kelling et al. 2015), thus improving our interpretation of the distribution of species. Specifically, the ability to obtain information on a large territorial scale can be integrated into studies based on Species Distribution Models SDMs. One of the common problems with SDMs is that they often work from species occurrences that have been opportunistically recorded, either by professionals or amateurs. A great challenge for data obtained from non-professional citizens, however, remains to ensure its standardization and quality (Kosmala et al. 2016). This requires a clear and effective design, solid volunteer training, and a high level of coordination that turns out to be complex (Brown and Williams 2019). Finally, it is essential to perform a quality validation following scientifically recognized standards, since they are often conditioned by errors and biases in obtaining information (Bird et al. 2014). There are two basic approaches to obtain the necessary data for this validation: getting it from an external source (external validation), or allocating a part of the database itself (internal validation or cross-validation) to this function. References [1] Bird TJ et al. (2014) Statistical solutions for error and bias in global citizen science datasets. Biological Conservation 173: 144-154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.07.037 | How citizen science could improve Species Distribution Models and their independent assessment | Florence Matutini, Jacques Baudry, Guillaume Pain, Morgane Sineau, Josephine Pithon | <p>Species distribution models (SDM) have been increasingly developed in recent years but their validity is questioned. Their assessment can be improved by the use of independent data but this can be difficult to obtain and prohibitive to collect.... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Conservation biology, Habitat selection, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology | Francisco Lloret | 2020-06-03 09:36:34 | View | ||

29 Dec 2018

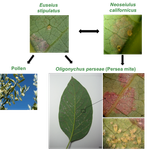

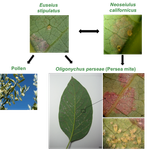

The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food webInmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat https://doi.org/10.1101/324178From deserts to avocado orchards - understanding realized trophic interactions in communitiesRecommended by Francis John Burdon based on reviews by Owen Petchey and 2 anonymous reviewersThe late eminent ecologist Gary Polis once stated that “most catalogued food-webs are oversimplified caricatures of actual communities” and are “grossly incomplete representations of communities in terms of both diversity and trophic connections.” Not content with that damning indictment, he went further by railing that “theorists are trying to explain phenomena that do not exist” [1]. The latter critique might have been push back for Robert May´s ground-breaking but ultimately flawed research on the relationship between food-web complexity and stability [2]. Polis was a brilliant ecologist, and his thinking was clearly influenced by his experiences researching desert food webs. Those food webs possess an uncommon combination of properties, such as frequent omnivory, cannibalism, and looping; high linkage density (L/S); and a nearly complete absence of apex consumers, since few species completely lack predators or parasites [3]. During my PhD studies, I was lucky enough to visit Joshua Tree National Park on the way to a conference in New England, and I could immediately see the problems posed by desert ecosystems. At the time, I was ruminating on the “harsh-benign” hypothesis [4], which predicts that the relative importance of abiotic and biotic forces should vary with changes in local environmental conditions (from harsh to benign). Specifically, in more “harsh” environments, abiotic factors should determine community composition whilst weakening the influence of biotic interactions. However, in the harsh desert environment I saw first-hand evidence that species interactions were not diminished; if anything, they were strengthened. Teddy-bear chollas possessed murderously sharp defenses to protect precious water, creosote bushes engaged in belowground “chemical warfare” (allelopathy) to deter potential competitors, and rampant cannibalism amongst scorpions drove temporal and spatial ontogenetic niche partitioning. Life in the desert was hard, but you couldn´t expect your competition to go easy on you. References [1] Polis, G. A. (1991). Complex trophic interactions in deserts: an empirical critique of food-web theory. The American Naturalist, 138(1), 123-155. doi: 10.1086/285208 | The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web | Inmaculada Torres-Campos, Sara Magalhães, Jordi Moya-Laraño, Marta Montserrat | <p>The mathematical theory describing small assemblages of interacting species (community modules or motifs) has proved to be essential in understanding the emergent properties of ecological communities. These models use differential equations to ... |  | Community ecology, Experimental ecology | Francis John Burdon | 2018-05-16 19:34:10 | View | |

03 Jan 2024

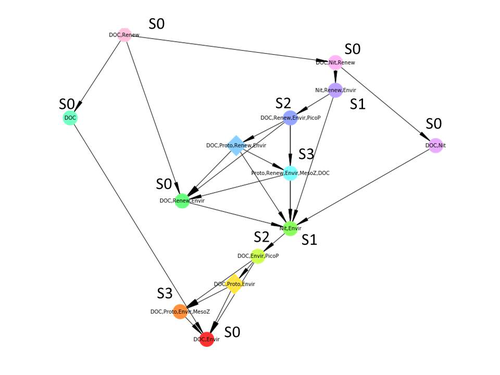

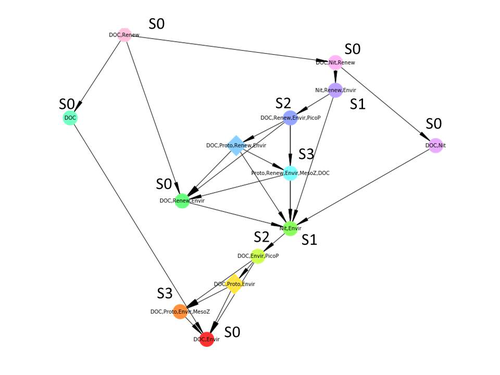

Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changesCedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055A new approach to describe qualitative changes of complex trophic networksRecommended by Francis Raoul based on reviews by Tim Coulson and 1 anonymous reviewerModelling the temporal dynamics of trophic networks has been a key challenge for community ecologists for decades, especially when anthropogenic and natural forces drive changes in species composition, abundance, and interactions over time. So far, most modelling methods fail to incorporate the inherent complexity of such systems, and its variability, to adequately describe and predict temporal changes in the topology of trophic networks. Taking benefit from theoretical computer science advances, Gaucherel and colleagues (2024) propose a new methodological framework to tackle this challenge based on discrete-event Petri net methodology. To introduce the concept to naïve readers the authors provide a useful example using a simplistic predator-prey model. The core biological system of the article is a freshwater trophic network of western France in the Charente-Maritime marshes of the French Atlantic coast. A directed graph describing this system was constructed to incorporate different functional groups (phytoplankton, zooplankton, resources, microbes, and abiotic components of the environment) and their interactions. Rules and constraints were then defined to, respectively, represent physiochemical, biological, or ecological processes linking network components, and prevent the model from simulating unrealistic trajectories. Then the full range of possible trajectories of this mechanistic and qualitative model was computed. The model performed well enough to successfully predict a theoretical trajectory plus two trajectories of the trophic network observed in the field at two different stations, therefore validating the new methodology introduced here. The authors conclude their paper by presenting the power and drawbacks of such a new approach to qualitatively model trophic networks dynamics. Reference Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy (2024) Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes. bioRxiv 2023.06.29.547055, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.06.29.547055 | Diagnosis of planktonic trophic network dynamics with sharp qualitative changes | Cedric Gaucherel, Stolian Fayolle, Raphael Savelli, Olivier Philippine, Franck Pommereau, Christine Dupuy | <p>Trophic interaction networks are notoriously difficult to understand and to diagnose (i.e., to identify contrasted network functioning regimes). Such ecological networks have many direct and indirect connections between species, and these conne... |  | Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Interaction networks, Microbial ecology & microbiology | Francis Raoul | Tim Coulson | 2023-07-03 10:42:34 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle