MORA-CARRERA Emiliano

- Institute of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Recommendations: 0

Review: 1

Review: 1

Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heterostylous invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala

Water primerose (Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala) auto- and allogamy: an ecological perspective

Recommended by Antoine Vernay based on reviews by Juan Arroyo, Emiliano Mora-Carrera and 1 anonymous reviewerInvasive plant species are widely studied by the ecologist community, especially in wetlands. Indeed, alien plants are considered one of the major threats to wetland biodiversity (Reid et al., 2019). Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G.L.Nesom & Kartesz, 2000 (Lgh) is one of them and has received particular attention for a long time (Hieda et al., 2020; Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiebaut, 2013). The ecology of this invasive species and its effect on its biotic and abiotic environment has been studied in previous works. Different processes were demonstrated to explain their invasibility such as allelopathic interference (Dandelot et al., 2008), resource competition (Gérard et al., 2014), and high phenotypic plasticity (Thouvenot, Haury, & Thiébaut, 2013), to cite a few of them. However, although vegetative reproduction is a well-known invasive process for alien plants like Lgh (Glover et al., 2015), the sexual reproduction of this species is still unclear and may help to understand the Lgh population dynamics.

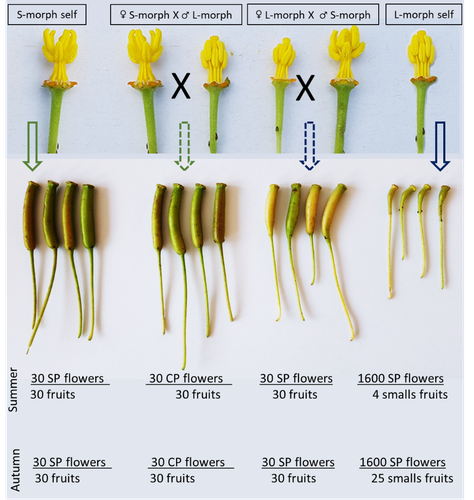

Portillo Lemus et al. (2021) showed that two floral morphs of Lgh co-exist in natura, involving self-compatibility for short-styled phenotype and self-incompatibility for long-styled phenotype processes. This new article (Portillo Lemus et al., 2022) goes further and details the underlying mechanisms of the sexual reproduction of the two floral morphs.

Complementing their previous study, the authors have described a late self-incompatible process associated with the long-styled morph, which authorized a small proportion of autogamy. Although this represents a small fraction of the L-morph reproduction, it may have a considerable impact on the L-morph population dynamics. Indeed, authors report that “floral morphs are mostly found in allopatric monomorphic populations (i.e., exclusively S-morph or exclusively L-morph populations)” with a large proportion of L-morph populations compared to S-morph populations in the field. It may seem counterintuitive as L-morph mainly relies on cross-fecundation.

Results show that L-morph autogamy mainly occurs in the fall, late in the reproduction season. Therefore, the reproduction may be ensured if no exogenous pollen reaches the stigma of L-morph individuals. It partly explains the large proportion of L-morph populations in the field.

Beyond the description of late-acting self-incompatibility, which makes the Onagraceae a third family of Myrtales with this reproductive adaptation, the study raises several ecological questions linked to the results presented in the article. First, it seems that even if autogamy is possible, Lgh would favour allogamy, even in S-morph, through the faster development of pollen tubes from other individuals. This may confer an adaptative and evolutive advantage for the Lgh, increasing its invasive potential. The article shows this faster pollen tube development in S-morph but does not test the evolutive consequences. It is an interesting perspective for future research. It would also be interesting to describe cellular processes which recognize and then influence the speed of the pollen tube. Second, the importance of sexual reproduction vs vegetative reproduction would also provide information on the benefits of sexual dimorphism within populations. For instance, how fruit production increases the dispersal potential of Lgh would help to understand Lgh population dynamics and to propose adapted management practices (Delbart et al., 2013; Meisler, 2009).

To conclude, the study proposes a morphological, reproductive and physiological description of the Lgh sexual reproduction process. However, underlying ecological questions are well included in the article and the ecophysiological results enlighten some questions about the role of sexual reproduction in the invasiveness of Lgh. I advise the reader to pay attention to the reviewers’ comments; the debates were very constructive and, thanks to the great collaboration with the authorship, lead to an interesting paper about Lgh reproduction and with promising perspectives in ecology and invasion ecology.

References

Dandelot S, Robles C, Pech N, Cazaubon A, Verlaque R (2008) Allelopathic potential of two invasive alien Ludwigia spp. Aquatic Botany, 88, 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2007.12.004

Delbart E, Mahy G, Monty A (2013) Efficacité des méthodes de lutte contre le développement de cinq espèces de plantes invasives amphibies : Crassula helmsii, Hydrocotyle ranunculoides, Ludwigia grandiflora, Ludwigia peploides et Myriophyllum aquaticum (synthèse bibliographique). BASE, 17, 87–102. https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=9586

Gérard J, Brion N, Triest L (2014) Effect of water column phosphorus reduction on competitive outcome and traits of Ludwigia grandiflora and L. peploides, invasive species in Europe. Aquatic Invasions, 9, 157–166. https://doi.org/10.3391/ai.2014.9.2.04

Glover R, Drenovsky RE, Futrell CJ, Grewell BJ (2015) Clonal integration in Ludwigia hexapetala under different light regimes. Aquatic Botany, 122, 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.01.004

Hieda S, Kaneko Y, Nakagawa M, Noma N (2020) Ludwigia grandiflora (Michx.) Greuter & Burdet subsp. hexapetala (Hook. & Arn.) G. L. Nesom & Kartesz, an Invasive Aquatic Plant in Lake Biwa, the Largest Lake in Japan. Acta Phytotaxonomica et Geobotanica, 71, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.18942/apg.201911

Meisler J (2009) Controlling Ludwigia hexaplata in Northern California. Wetland Science and Practice, 26, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1672/055.026.0404

Portillo Lemus LO, Harang M, Bozec M, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2022) Late-acting self-incompatible system, preferential allogamy and delayed selfing in the heteromorphic invasive populations of Ludwigia grandiflora subsp. hexapetala. bioRxiv, 2021.07.15.452457, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.15.452457

Portillo Lemus LO, Bozec M, Harang M, Coudreuse J, Haury J, Stoeckel S, Barloy D (2021) Self-incompatibility limits sexual reproduction rather than environmental conditions in an invasive water primrose. Plant-Environment Interactions, 2, 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/pei3.10042

Reid AJ, Carlson AK, Creed IF, Eliason EJ, Gell PA, Johnson PTJ, Kidd KA, MacCormack TJ, Olden JD, Ormerod SJ, Smol JP, Taylor WW, Tockner K, Vermaire JC, Dudgeon D, Cooke SJ (2019) Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biological Reviews, 94, 849–873. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12480

Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiebaut G (2013) A success story: water primroses, aquatic plant pests. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 23, 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.2387

Thouvenot L, Haury J, Thiébaut G (2013) Seasonal plasticity of Ludwigia grandiflora under light and water depth gradients: An outdoor mesocosm experiment. Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 208, 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.004