GRENIÉ Matthias

- Pharmacy Faculty, Université Grenoble Alpes, Saint-Martin-d'Hères, France

- Biodiversity, Biogeography, Biological invasions, Community ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology

Recommendations: 0

Review: 1

Review: 1

On the quest for novelty in ecology

From Paradigm to Publication: What Does the Pursuit of Novelty Reveal in Ecology?

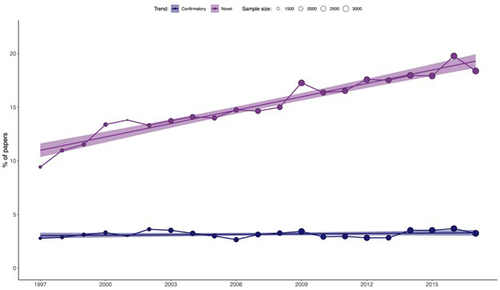

Recommended by François Munoz based on reviews by Francois Massol, Matthias Grenié and 1 anonymous reviewerIn this study, Ottaviani et al. (2025) examined the variation in the use of terms related to "novelty" in 52,236 abstracts published between 1997 and 2017 across 17 ecological journals. They also analyzed the change in the frequency of terms related to "confirmatory" results. Their findings revealed a clear and consistent increase in the use of "novelty" terms, while the frequency of "confirmatory" terms remained relatively stable. This trend was observed across all the ecological journals, with the exception of Austral Ecology. Furthermore, the greater use of "novelty" terms was correlated with higher citation counts and publication in journals with higher impact factors. These findings should prompt further reflection on our research practices and may be connected to ongoing discussions in the philosophy of science.

Thomas S. Kuhn's seminal work, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), challenged traditional views of scientific progress. Central to Kuhn's argument is the idea that science progresses through periods of adherence to a dominant "paradigm"—a framework that provides scientists with puzzles to solve and the tools to solve them. A scientific crisis arises when the paradigm fails to address emerging anomalies, leading to the replacement of the old paradigm with a new one, a process Kuhn calls a "scientific revolution." Kuhn's perspective stands in stark contrast to previous views, which held that science progresses through the steady accumulation of truths or the gradual refinement of theories, often guided by the scientific method. One might wonder if the growing emphasis on "novelty" in ecological research mirrors the idea that theories are gradually refined until an exceptional discovery sparks a paradigm shift. In ecology, such a shift could be seen in the transition from niche-based theories of biodiversity dynamics (1960s-2000) to the radical neutral theory (Hubbell, 2001), which posits that diverse ecosystems can exist without niche differences. This paradigm was initially met with fierce opposition but eventually led to more integrative theories, recognizing the combined influence of both niche-based and neutral processes (Gravel et al., 2006, among others).

What, then, is the current paradigm in ecology? Kuhn's theory of scientific progress suggests alternating periods of "normal" and "revolutionary" science. Normal science is characterized by cumulative puzzle-solving within established frameworks, while revolutionary science involves major shifts that can invalidate previous knowledge, a phenomenon Kuhn terms "Kuhn-loss." Kuhn rejected both the traditional and Popperian views on scientific revolutions. He argued that normal science depends on a shared commitment to certain beliefs, values, methods, and even metaphysical assumptions, which he referred to as a "disciplinary matrix" or "paradigm." This collective commitment is essential for scientific progress and must be instilled during the training of scientists. Kuhn's emphasis on the conservative nature of normal science contrasts with the heroic idea of continuous innovation and Popper's view of scientists constantly seeking to falsify theories. However, contemporary ecological research often follows the hypothetico-deductive approach championed by Popper. In light of these contrasting views, one might ask: What is the status of "novelty" in modern ecology? Is it contributing to the gradual solving of scientific puzzles, or is it focused on refuting hypotheses? Should "novelty" and "confirmatory" research be seen as opposites, or should both contribute to the advancement of science? Finally, is the increasing use of "novelty" terms a precursor to a scientific revolution, as Kuhn defined it, or merely a semantic trend driven by editorial policies aimed at attracting readers rather than contributing to real scientific progress?

In conclusion, Ottaviani's study provides compelling evidence of the growing use of "novelty" terms in ecological journals, but it remains unclear whether this trend signals the onset of a Kuhnian "scientific revolution." This work should spark further discussion on the nature of current research practices, which may either facilitate or hinder the emergence of new paradigms.

References

Gravel, D., Canham, C. D., Beaudet, M., & Messier, C. (2006). Reconciling niche and neutrality: the continuum hypothesis. Ecology letters, 9(4), 399-409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2006.00884.x

Hubbell, S. P. (2001). The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography, vol.1, Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, vol.2, 1962.

Ottaviani, G., Martinez, A., Petit Bon, M., Mammola, S. (2025). On the quest for novelty in ecology. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.27.530333