BARRAQUAND Frédéric

- Institut de Mathématiques de Bordeaux, CNRS, Bordeaux, France

- Behaviour & Ethology, Biological control, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Demography, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism, Food webs, Foraging, Host-parasite interactions, Interaction networks, Landscape ecology, Life history, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Review: 1

Recommendation: 1

In defense of the original Type I functional response: The frequency and population-dynamic effects of feeding on multiple prey at a time

Revising behavioural assumptions leads to a new appreciation of an old functional response model

Recommended by Frédéric Barraquand based on reviews by Matthieu Barbier and Wojciech UszkoThe functional response, describing the relation between predator intake rate and prey density, is a pivotal concept to understand foraging behaviour and its consequences for community dynamics. Holling (1959a) introduced three types of functional responses according to their shapes, labelled I, II and III. The type II, also known as the disc equation (Holling 1959b), has become popular among empiricists and theoreticians alike, due to its ability to describe predator intake saturation. The type III is often used to represent predator switching to other prey species when main prey density is low.

Although theoretical works identify the linear functional response used in Lotka-Volterra models as a type I, Holling (1959a)’s type I model actually envisioned that at some threshold prey density, the linear increase in predator intake with prey density would give way to an upper predator intake limit, so that Holling’s type I has a rectilinear shape, with an angle joining straight lines. Ecology students can actually see this rectilinear shape reproduced in some texbooks, although not in textbook dynamical models, as they usually transition from Lotka-Volterra models to models with type II response.

To many, the rectilinear shape of the original type I looks like a historical curiosity: the type II functional response accounts for intake rate saturation with a more convenient smooth function.

Novak et al. (2025) turn this preconception on its head by first pedagogically showing that Holling’s original type I model can be obtained as a limit case of a variant of the celebrated type II model. The derivation follows up earlier work by Sjöberg (1980), which might be unfamiliar to readers outside aquatic ecology. The often untold assumption of the type II functional response model is that searching and handling prey are two exclusive behavioural processes, with predators that can only handle one prey item at a time. Allowing for several prey items to be handled at once while searching, until the predator reaches n prey items, the original type I functional response emerges as a limit case of the « multiprey » functional response as n goes to infinity. Interestingly, the multiprey response looks a lot like the original type I for large yet doable n.

Novak et al. (2025) then proceed to look for the prevalence of such multiprey functional response shapes in a large database of functional responses (Uiterwaal et al. 2022). Combining linear type I and multiprey models (the asymptote may not always be visible), they find support for this revised type I hypothesis in about one-third of the cases. Although the type II and III models are still well supported by data, the results do suggest that linearity at low prey density may well be more frequent than one thinks. They complement this analysis by showing that larger predators relative to their prey tend to have larger n in the multiprey response. It is consistent with the hypothesis that the bigger you are relative to your prey, the more prey items you can handle at once.

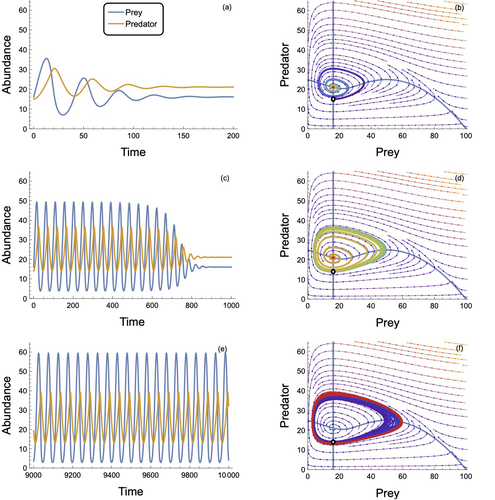

Finally, Novak et al. (2025) investigate the consequences of the multiprey model for community dynamics. They find overall a richer dynamical behaviour than the Lotka-Volterra type I and common parameterizations of the type II, suggesting that observed linearity in some range of prey density does not necessarily translate in simpler dynamical behaviour.

Novak et al. (2025) provide here a convincing and pedagogical study showing how seemingly benign behavioural assumptions can in fact profoundly alter the perceived relevance of community dynamics models. As they conclude, their analyses have lessons for future empirical functional response work, which should not necessarily dismiss the type I model and consider perhaps variants to the classical type II and III, as well as for future theoretical analyses, which could generalize this model to multiple prey species, or relax other behavioural assumptions.

References

Holling, C. S. (1959a). The components of predation as revealed by a study of small-mammal predation of the European Pine Sawfly. The Canadian Entomologist, 91(5), 293-320. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent91293-5

Holling, C. S. (1959b). Some characteristics of simple types of predation and parasitism. The Canadian Entomologist, 91(7), 385-398. https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent91385-7

Novak, M., Coblentz, K. E., & DeLong, J. P (2025). In defense of the original Type I functional response: The frequency and population-dynamic effects of feeding on multiple prey at a time. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.14.594210

Sjöberg, S. (1980). Zooplankton feeding and queueing theory. Ecological Modelling, 10(3-4), 215-225. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3800(80)90060-5

Uiterwaal, S. F., Lagerstrom, I. T., Lyon, S. R., & DeLong, J. P. (2022). FoRAGE database: A compilation of functional responses for consumers and parasitoids. Ecology, 103(7), e3706. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3706

Review: 1

The inherent multidimensionality of temporal variability: How common and rare species shape stability patterns

Diversity-Stability and the Structure of Perturbations

Recommended by Kevin Cazelles and Kevin Shear McCann based on reviews by Frédéric Barraquand and 1 anonymous reviewerIn his 1972 paper “Will a Large Complex System Be Stable?” [1], May challenges the idea that large communities are more stable than small ones. This was the beginning of a fundamental debate that still structures an entire research area in ecology: the diversity-stability debate [2]. The most salient strength of May’s work was to use a mathematical argument to refute an idea based on the observations that simple communities are less stable than large ones. Using the formalism of dynamical systems and a major results on the distribution of the eigen values for random matrices, May demonstrated that the addition of random interactions destabilizes ecological communities and thus, rich communities with a higher number of interactions should be less stable. But May also noted that his mathematical argument holds true only if ecological interactions are randomly distributed and thus concluded that this must not be true! This is how the contradiction between mathematics and empirical observations led to new developments in the study of ecological networks.

Since 1972, the theoretical corpus of ecology has advanced, building on the formalism of dynamical systems, ecologists have revealed that ecological interactions are indeed not randomly distributed [3,4], but general rules are still missing and we are far from understanding what determine the exact network topology of a given community. One promising avenue is to understand the relationship between different facets of the concept of stability [5,6]. Indeed, the classical approach to determine whether a system is stable is qualitative: if a system returns to its equilibrium when it is slightly moved away from it, then the system is considered stable. But there are several other aspects that are worth scrutinizing. For instance, when a system returns to its equilibrium, one can characterize the corresponding transient dynamics [7,8], that is asking fundamental questions such as: what is the trajectory of return? How long does it take to return to the equilibrium? Another fundamental question is whether the system remains qualitatively stable when the distributions of interactions strengths change? From a biological standpoint, all of these questions matter as all these aspects of stability may partially explain the actual structure of ecological networks, and hence, frameworks that integrate several facets of stability are much needed.

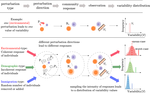

The study by Arnoldi et al. [9] is a significant step towards such a framework. The strength of their formalism is threefold. First, instead of considering separately the system and its perturbations, they considering the fluctuations of a perturbed ecological systems and thus, perturbations are parts of the ecological system. Second, they use of a broad definition of perturbation that encompasses the types of perturbations (whether the individual respond synchronously or not), their intensity and their direction (how the perturbations are correlated across species). Third, they quantify the instability of the system using variability which integrates the consequences of perturbations over the whole set of species of a community: such a measure is comparable across communities and accounts for the trivial effect of the perturbations on the system dynamics.

Using this framework, the authors show that interactions within a stable community leads to a general relationship between variability and the abundance of individually perturbed species: if individuals of species respond in synchrony to a perturbation, then the more abundant the species perturbed the higher the variability of the system, but the relationship is reverse when individual respond asynchronously. A direct implications of these results for the classical debate is that the diversity-stability relationship is negative for the former type of perturbations (as in May’s seminal paper) but positive for the latter type. Hence, the rigorous work of Arnoldi and colleagues sheds a new light upon the classical debate: the nature of the perturbation regime prevailing within a community affects the slope of the diversity-stability relationships and given the vast diversity of ecological communities, this may very well be one of the reasons why the debate still endures.

From a historical perspective, it is interesting that ecologists have gone from looking at random webs to structured webs and now, in a sense, Arnoldi et al. are unpacking the role of differentially structured perturbations. The work they achieved will doubtlessly be followed by further theoretical investigations. One natural research avenue is to revisit the role of the topology of ecological networks with this framework: how the distribution of interactions and their strength affect the general relationship they unravel? Finally, this study demonstrate that the impact of the abundance of a species on the variability of the system depends on the nature of the perturbation regime and so the distribution of species abundances within a community should be determined by the prevailing perturbation regime which is a prediction that remains to be tested.

References

[1] May, Robert M (1972). Will a Large Complex System Be Stable? Nature 238, 413–414. doi: 10.1038/238413a0

[2] McCann, Kevin Shear (2000). The Diversity–Stability Debate. Nature 405, 228–233. doi: 10.1038/35012234

[3] Rooney, Neil, Kevin McCann, Gabriel Gellner, and John C. Moore (2006). Structural Asymmetry and the Stability of Diverse Food Webs. Nature 442, 265–269. doi: 10.1038/nature04887

[4] Jacquet, Claire, Charlotte Moritz, Lyne Morissette, Pierre Legagneux, François Massol, Philippe Archambault, and Dominique Gravel (2016). No Complexity–Stability Relationship in Empirical Ecosystems. Nature Communications 7, 12573. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12573

[5] Donohue, Ian, Helmut Hillebrand, José M. Montoya, Owen L. Petchey, Stuart L. Pimm, Mike S. Fowler, Kevin Healy, et al. (2016). Navigating the Complexity of Ecological Stability. Ecology Letters 19, 1172–1185. doi: 10.1111/ele.12648

[6] Arnoldi, Jean-François, and Bart Haegeman (2016). Unifying Dynamical and Structural Stability of Equilibria. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Science 472, 20150874. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2015.0874

[7] Caswell, Hal, and Michael G. Neubert (2005). Reactivity and Transient Dynamics of Discrete-Time Ecological Systems. Journal of Difference Equations and Applications 11, 295–310. doi: 10.1080/10236190412331335382

[8] Arnoldi, J-F., M. Loreau, and B. Haegeman (2016). Resilience, Reactivity and Variability: A Mathematical Comparison of Ecological Stability Measures. Journal of Theoretical Biology 389, 47–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2015.10.012

[9] Arnoldi, Jean-Francois, Michel Loreau, and Bart Haegeman. (2019). The Inherent Multidimensionality of Temporal Variability: How Common and Rare Species Shape Stability Patterns.” BioRxiv, 431296, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/431296