Review: 1

Is the audience gender-blind? Smaller attendance in female talks highlights imbalanced visibility in academia

Gender matters: smaller audiences for women in academia

Recommended by Natalia Mariel Schroeder based on reviews by Silvia Beatriz Lomascolo and Letícia dos AnjosThe current lack of social diversity - that is, gender, race and ethnicity - in academia reinforces a historical pattern of exclusion, wherein the knowledge, perspectives and advances of certain groups dominate the narrative, set rhythms and agenda, while the contributions of others are minimised or overlooked. The underrepresentation of and discrimination against women in academia is a well-documented and persistent issue. Despite policies designed to increase female representation and mitigate the structural processes that lead women to abandon their academic careers (Shaw & Stanton, 2012), women scientists continue to face inequalities in authorship, publications, funding, salaries, recognition and decision-making spaces (Astegiano et al., 2019, Woolston, 2019; Fox et a. 2023; Fontanarrosa et al. 2024; Zandonà, 2022; among others). Making these inequalities visible and fostering open discussion is a critical first step toward dismantling them. In this sense, the study by Rodrigues Barreto et al. (2025) makes an important contribution. The authors examine gender bias in seminar series within the field of Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology at the University of São Paulo (Brazil), using audience size as an indirect measure of speaker recognition.

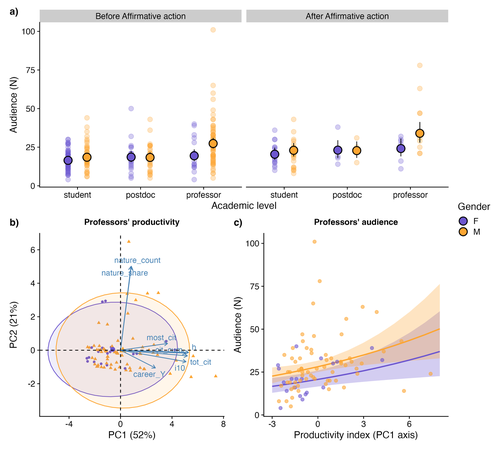

The most interesting and novel finding of this work is that talks given by women -especially by female professors- attract smaller audiences than those given by men counterparts, despite the women having comparable levels of academic productivity, similar career trajectories, and presenting on equivalent topics to those of their male colleagues. These results suggest that seminar culture is not gender-blind (Dupas et al., 2021) and provide a new layer of evidence on how gender-based stereotypes continue to influence the visibility and recognition of women in science.

The authors also investigated whether the implementation of affirmative actions (i.e., open calls for volunteer speakers that prioritised women) improved both the representation of female speakers and the size of their audiences. As expected, these actions did succeed in increasing the representation of women among presenters, especially at senior academic levels; however, they did not lead to a proportional rise in audience size. While the time series and number of talks considered before the implementation of affirmative actions were considerably higher than those after this policy, the comparison remains relevant given the importance and timeliness of the topic.

The authors found that women give fewer talks than men. However, as they discuss, their results do not allow them to distinguish whether this inequality is due to gender bias or to a structural gender imbalance. Through a supplementary analysis of a subset of data from the University of São Paulo community, they find some evidence that the underrepresentation of women in the academic population itself may partly explain the gender gap in the seminar series. In any case, these findings, along with similar results from other studies (e.g. Greska, 2023) raise valuable questions: Will simply increasing the number of women in academia be enough to close the recognition gap between men and women scholars? What role might affirmative actions play in attracting a wider audience or enhancing the visibility and recognition of women's work? What kinds of initiatives could change the way we acknowledge women researchers’ contributions? What could reconfigure that “recognition landscape” from a feminist perspective, i.e., one less competitive, less hierarchical, more communitarian and less individual-centered?

As the authors acknowledge, the study has limitations (e.g., its focus on a single institution, a short timeframe to assess the impact of affirmative actions), but it provides valuable evidence to initiate broader approaches that include other disciplines, institutions, experimental approaches, and intersectional perspectives.

References

Astegiano J, Sebastián-González E, Castanho C de T (2019) Unravelling the gender 465 productivity gap in science: a meta-analytical review. Royal Society Open Science 6: 466 181566. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.181566

Dupas P, Modestino AS, Niederle M, Wolfers J, Collective TSD (2021) Gender and the Dynamics of Economics Seminars. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w28494.pdf

Fontanarrosa, G., Zarbá, L., Aschero, V., Dos Santos, D. A., Montellano, M. G. N. et al. (2024). Over twenty years of publications in Ecology: Over-contribution of women reveals a new dimension of gender bias. PLoS ONE 19(9): e0307813. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0307813

Fox CW, Meyer J, Aimé E (2023) Double-blind peer review affects reviewer ratings and 509 editor decisions at an ecology journal. Functional Ecology 37: 1144–1157. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14259

Greska L (2023) Women in Academia: Why and where does the pipeline leak, and how can we fix it? MIT Science Policy Review 4: 102–109. https://doi.org/10.38105/spr.xmvdiojee1

Rodrigues Barreto J, Romitelli I, Santana PC, Aprígio Assis A.N., Pardini R, de Souza Leite M. (2025) Is the audience gender-blind? Smaller attendance in female talks highlights imbalanced visibility in academia. EcoEvoRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology https://doi.org/10.32942/X25607

Shaw AK, Stanton DE (2012) Leaks in the pipeline: separating demographic inertia from ongoing gender differences in academia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279: 3736–3741. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.0822

Woolston C (2019) Scientists’ salary data highlight US$18,000 gender pay gap. Nature 565: 597 527–527. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00220-y

Zandonà E (2022) Female ecologists are falling from the academic ladder: A call for action. 602 Perspectives in Ecology and Conservation 20: 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecon.2022.04.001