OPPEL Steffen

- Ecological Research Unit, Swiss Ornithological Institute, Sempach, Switzerland

- Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Demography, Dispersal & Migration, Population ecology

Recommendations: 0

Review: 1

Review: 1

Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity: case study on the arboreal-nesting red kite (Milvus milvus)

Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young: you may count too many or too few...

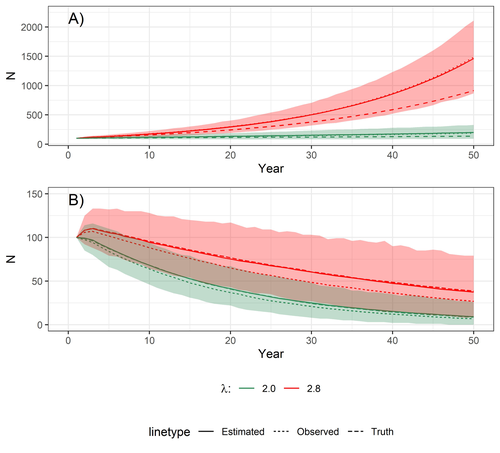

Recommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by Steffen Oppel and 1 anonymous reviewerMost species are hard to observe, and different methods are required to estimate demographic parameters such as the number of young individuals produced (one measure of breeding success) and survival. In the former case, and in particular for birds of prey, it often relies upon direct observations of breeding pairs on their nests. Two problems can then occur, that some young are missed and therefore the breeding success is underestimated (“false negatives”), but it is also possible that because for example of the nest structure or vegetation surrounding the nest, more young birds than in fact are present are counted (“false positives”). Sollmann et al. (2024) address this problem by using data where the truth is known as each nest was also accessed after climbing the tree, and a hierarchical model accounting for both undercounts and overcounts. Finally, they assess the impact of this correction on projected population size using simulations.

This paper is a solid contribution to the panoply of methods and models that are available for monitoring populations, and has potential applications for many species for which both false positives and false negatives can be a problem. The results on the projected population sizes – showing that for growing populations correcting for bias can lead to large differences in population sizes after a few decades – may seem counterintuitive as population growth rate of long-lived species such as birds of prey is not very sensitive to a change in breeding success (as compared to adult survival). However, one should just be reminded that a small difference in population growth rate may translate to a large difference after many years – for example a growth rate of 1.05 after 50 years mean than population size is multiplied by 11.5, whereas a growth of 1.03 after 50 years mean a multiplication by 4.4, more than twice less individuals. Small differences may matter a lot if they are sustained, and a key aspect of management is to ensure that they are. Of course, management actions having an impact on survival may be more effective, but they might be harder to achieve than for example ensuring that birds of prey breed successfully.

References

Sollmann Rahel, Adenot Nathalie, Spakovszky Péter, Windt Jendrik, Mattsson Brady J. 2024. Accounting for observation biases associated with counts of young when estimating fecundity. bioRxiv, v. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.12.01.569571