CASKENETTE Amanda Lynn

- Freshwater Institute, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Winnipeg, Canada

- Biological invasions, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Food webs, Foraging, Freshwater ecology, Habitat selection, Life history, Marine ecology, Maternal effects, Ontogeny, Phenotypic plasticity, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Review: 1

Recommendation: 1

Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems

Adaptive harvesting, “fishing down the food web”, and regime shifts

Recommended by Amanda Lynn Caskenette based on reviews by Pierre-Yves HERNVANN and 1 anonymous reviewerThe mean trophic level of catches in world fisheries has generally declined over the 20th century, a phenomenon called "fishing down the food web" (Pauly et al. 1998). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain this decline including the collapse of, or decline in, higher trophic level stocks leading to the inclusion of lower trophic level stocks in the fishery. Fishing down the food web may lead to a reduction in the resilience, i.e., the capacity to rebound from change, of the fished community, which is concerning given the necessity of resilience in the face of climate change.

The practice of adaptive harvesting, which involves fishing stocks based on their availability, can also result in a reduction in the average trophic level of a fishery (Branch et al. 2010). Adaptive harvesting, similar to adaptive foraging, can affect the resilience of fisheries. Generally, adaptive foraging acts as a stabilizing force in communities (Valdovinos et al. 2010), however it is not clear how including harvesters as the adaptive foragers will affect the resilience of the system.

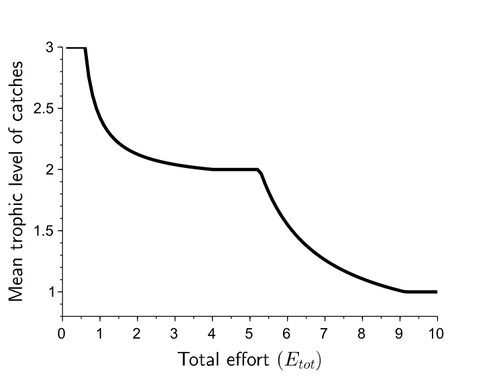

Tromeur and Loeuille (2023) analyze the effects of adaptively harvesting a trophic community. Using a system of ordinary differential equations representing a predator-prey model where both species are harvested, the researchers mathematically analyze the impact of increasing fishing effort and adaptive harvesting on the mean trophic level and resilience of the fished community. This is achieved by computing the equilibrium densities and equilibrium allocation of harvest effort. In addition, the researchers numerically evaluate adaptive harvesting in a tri-trophic system (predator, prey, and resource). The study focuses on the effect of adaptively distributing harvest across trophic levels on the mean trophic level of catches, the propensity for regime shifts to occur, the ability to return to equilibrium after a disturbance, and the speed of this return.

The results indicate that adaptive harvesting leads to a decline in the mean trophic level of catches, resulting in “fishing down the food web”. Furthermore, the study shows that adaptive harvesting may harm the overall resilience of the system. Similar results were observed numerically in a tri-trophic community.

While adaptive foraging is generally a stabilizing force on communities, the researchers found that adaptive harvesting can destabilize the harvested community. One of the key differences between adaptive foraging models and the model presented here, is that the harvesters do not exhibit population dynamics. This lack of a numerical response by the harvesters to decreasing population sizes of their stocks leads to regime shifts. The realism of a fishery that does not respond numerically to declining stock is debatable, however it is very likely that there will a least be significant delays due to social and economic barriers to leaving the fishery, that will lead to similar results.

This study is not unique in demonstrating the ability of adaptive harvesting to result in “fishing down the food web”. As pointed out by the researchers, the same results have been shown with several different model formulations (e.g., age and size structured models). Similarly, this study is not unique to showing that increasing adaptation speeds decreases the resilience of non-linear predator-prey systems by inducing oscillatory behaviours. Much of this can be explained by the destabilising effect of increasing interaction strengths on food webs (McCann et al. 1998).

By employing a straightforward model, the researchers were able to demonstrate that adaptive harvesting, a common strategy employed by fishermen, can result in a decline in the average trophic level of catches, regime shifts, and reduced resilience in the fished community. While previous studies have observed some of these effects, the fact that the current study was able to capture them all with a simple model is notable. This modeling approach can offer insight into the role of human behavior on the complex dynamics observed in fisheries worldwide.

References

Branch, T. A., R. Watson, E. A. Fulton, S. Jennings, C. R. McGilliard, G. T. Pablico, D. Ricard, et al. 2010. The trophic fingerprint of marine fisheries. Nature 468:431–435. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09528

Tromeur, E., and N. Loeuille. 2023. Effects of adaptive harvesting on fishing down processes and resilience changes in predator-prey and tritrophic systems. bioRxiv 290460, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/290460

McCann, K., A. Hastings, and G.R. Huxel. 1998. Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature 395: 794-798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427

Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Froese, and F. Torres Jr. 1998. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279:860–86. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.279.5352.860

Valdovinos, F.S., R. Ramos-Jiliberto, L. Garay-Naravez, P. Urbani, and J.A. Dunne. 2010. Consequences of adaptive behaviour for the structure and dynamics of food webs. Ecology Letters 13: 1546-1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01535.x

Review: 1

Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail

Escargots cooked just right: telling apart the direct and indirect effects of heat waves in freashwater snails

Recommended by vincent calcagno based on reviews by Amanda Lynn Caskenette, Kévin Tougeron and arnaud sentisAmongst the many challenges and forms of environmental change that organisms face in our era of global change, climate change is perhaps one of the most straightforward and amenable to investigation. First, measurements of day-to-day temperatures are relatively feasible and accessible, and predictions regarding the expected trends in Earth surface temperature are probably some of the most reliable we have. It appears quite clear, in particular, that beyond the overall increase in average temperature, the heat waves locally experienced by organisms in their natural habitats are bound to become more frequent, more intense, and more long-lasting [1]. Second, it is well appreciated that temperature is a major environmental factor with strong impacts on different facets of organismal development and life-history [2-4]. These impacts have reasonably clear mechanistic underpinnings, with definite connections to biochemistry, physiology, and considerations on energetics. Third, since variation in temperature is a challenge already experienced by natural populations across their current and historical ranges, it is not a completely alien form of environmental change. Therefore, we already learnt quite a lot about it in several species, and so did the species, as they may be expected to have evolved dedicated adaptive mechanisms to respond to elevated temperatures. Last, but not least, temperature is quite amenable to being manipulated as an experimental factor.

For all these reasons, experimental studies of the consequences of increased temperature hit some of a sweetspot and are a source of very nice research, in many different organisms. The work by Leicht and Seppala [5] complements a sequence of earlier studies by this group, using the freshwater snail Lymnaea stagnalis as their model system [6-7].

In the present study, the authors investigate how a heat wave (a period of abnormally elevated temperature, here 25°C versus a normal 15°C) may have indirect effects on the next generation, through maternal effects. They question whether such indirect effects exist, and if they exist, how they compare, in terms of effect size, with the (more straightforward) direct effects observed in individuals that directly experience a heat wave. Transgenerational effects are well-known to occur following periods of physiological stress, and might thus have non negligible contributions to the overall effect of warming.

In this freshwater snail, heat has very strong direct effects: mortality increases at high temperature, but survivors grow much bigger, with a greater propensity to lay eggs and a (spectacular) three-fold increase in the number of eggs laid [6]. Considering that, it is easy to consider that transgenerational effects should be small game. And indeed, the present study also observes the big and obvious direct effects of elevated temperature: higher mortality, but greater propensity to oviposit. However, it was also found that the eggs were smaller if from mothers exposed to high temperature, with a correspondingly smaller size of hatchlings. This suggests that a heat wave causes the snails to lay more eggs, but smaller ones, reminiscent of a size-number trade-off. Unfortunately, clutch size could not be measured in this experiment, so this cannot be investigated any further. For this trait, the indirect effect may indeed be regarded as small game : eggs and hatchlings were about 15 % smaller, an effect size pretty small compared to the mammoth direct positive effect of temperature on shell length (see Figure 4 ; and also [6]). The same is true for developmental time (Figure 3).

However, for some traits the story was different. In particular, it was found that the (smaller) eggs produced from heated mothers were more likely to hatch by almost 10% (Figure 2). Here the indirect effect not only goes against the direct effect (hatching rate is lower at high temperature), but it also has similar effect size. As a consequence, taking into account both the indirect and direct effects, hatching success is essentially the same at 15°C and 25°C (Figure 2). Survival also had comparable effect sizes for direct and indirect effects. Indeed, survival was reduced by about 20% regardless of whom endured the heat stress (the focal individual or her mother; Figure 4). Interestingly, the direct and indirect effects were not quite cumulative: if a mother experienced a heat wave, heating up the offspring did not do much more damage, as though the offspring were ‘adapted’ to the warmer conditions (but keep in mind that, surprisingly, the authors’ stats did not find a significant interaction; Table 2).

At the end of the day, even though at first heat seems a relatively simple and understandable component of environmental change, this study shows how varied its effects can be effects on different components of individual fitness. The overall impact most likely is a mix of direct and indirect effects, of shifts along allocation trade-offs, and of maladaptive and adaptive responses, whose overall ecological significance is not so easy to grasp. That said, this study shows that direct and indirect (maternal) effects can sometimes go against one another and have similar intensities. Indirect effects should therefore not be overlooked in this kind of studies. It also gives a hint of what an interesting challenge it is to understand the adaptive or maladaptive nature of organism responses to elevated temperatures, and to evaluate their ultimate fitness consequences.

References

[1] Meehl, G. A., & Tebaldi, C. (2004). More intense, more frequent, and longer lasting heat waves in the 21st century. Science (New York, N.Y.), 305(5686), 994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1098704

[2] Adamo, S. A., & Lovett, M. M. E. (2011). Some like it hot: the effects of climate change on reproduction, immune function and disease resistance in the cricket Gryllus texensis. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 214(Pt 12), 1997–2004. doi: 10.1242/jeb.056531

[3] Deutsch, C. A., Tewksbury, J. J., Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D. S., Merrill, S. C., Huey, R. B., & Naylor, R. L. (2018). Increase in crop losses to insect pests in a warming climate. Science (New York, N.Y.), 361(6405), 916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.aat3466

[4] Sentis, A., Hemptinne, J.-L., & Brodeur, J. (2013). Effects of simulated heat waves on an experimental plant–herbivore–predator food chain. Global Change Biology, 19(3), 833–842. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12094

[5] Leicht, K., & Seppälä, O. (2019). Direct and transgenerational effects of an experimental heat wave on early life stages in a freshwater snail. BioRxiv, 449777, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: 10.1101/449777

[6] Leicht, K., Seppälä, K., & Seppälä, O. (2017). Potential for adaptation to climate change: family-level variation in fitness-related traits and their responses to heat waves in a snail population. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17(1), 140. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0988-x

[7] Leicht, K., Jokela, J., & Seppälä, O. (2013). An experimental heat wave changes immune defense and life history traits in a freshwater snail. Ecology and Evolution, 3(15), 4861–4871. doi: 10.1002/ece3.874