BURDON Francis John

- Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden

- Biodiversity, Community ecology, Ecosystem functioning, Experimental ecology, Food webs, Freshwater ecology, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Statistical ecology

- recommender

Recommendation: 1

Review: 1

Recommendation: 1

The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web

From deserts to avocado orchards - understanding realized trophic interactions in communities

Recommended by Francis John Burdon based on reviews by Owen Petchey and 2 anonymous reviewersThe late eminent ecologist Gary Polis once stated that “most catalogued food-webs are oversimplified caricatures of actual communities” and are “grossly incomplete representations of communities in terms of both diversity and trophic connections.” Not content with that damning indictment, he went further by railing that “theorists are trying to explain phenomena that do not exist” [1]. The latter critique might have been push back for Robert May´s ground-breaking but ultimately flawed research on the relationship between food-web complexity and stability [2]. Polis was a brilliant ecologist, and his thinking was clearly influenced by his experiences researching desert food webs. Those food webs possess an uncommon combination of properties, such as frequent omnivory, cannibalism, and looping; high linkage density (L/S); and a nearly complete absence of apex consumers, since few species completely lack predators or parasites [3]. During my PhD studies, I was lucky enough to visit Joshua Tree National Park on the way to a conference in New England, and I could immediately see the problems posed by desert ecosystems. At the time, I was ruminating on the “harsh-benign” hypothesis [4], which predicts that the relative importance of abiotic and biotic forces should vary with changes in local environmental conditions (from harsh to benign). Specifically, in more “harsh” environments, abiotic factors should determine community composition whilst weakening the influence of biotic interactions. However, in the harsh desert environment I saw first-hand evidence that species interactions were not diminished; if anything, they were strengthened. Teddy-bear chollas possessed murderously sharp defenses to protect precious water, creosote bushes engaged in belowground “chemical warfare” (allelopathy) to deter potential competitors, and rampant cannibalism amongst scorpions drove temporal and spatial ontogenetic niche partitioning. Life in the desert was hard, but you couldn´t expect your competition to go easy on you.

If that experience colored my thinking about nature’s reaction to a capricious environment, then the seminal work by Robert Paine on the marine rocky shore helped further cement the importance of biotic interactions. The insights provided by Paine [5] brings us closer to the research reported in the preprint “The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web” [6], given that the authors in that study hold the environment constant and test the interactions between different permutations of a simple community. Paine [5] was able to elegantly demonstrate using the chief protagonist Pisaster ochraceus (a predatory echinoderm also known as the purple sea star) that a keystone consumer could exert strong top-down control that radically reshaped the interactions amongst other community members. What was special about this study was that the presence of Pisaster promoted species diversity by altering competition for space by sedentary species, providing a rare example of an ecological network experiment combining trophic and non-trophic interactions. Whilst there are increasing efforts to describe these interactions (e.g., competition and facilitation) in multiplex networks [7], the authors of “The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web” [6] have avoided strictly competitive interactions for the sake of simplicity. They do focus on two trophic forms of competition, namely intraguild predation and apparent competition. These two interaction motifs, along with prey switching are relevant to my own research on the influence of cross-ecosystem prey subsidies to receiving food webs [8]. In particular, the apparent competition motif may be particularly important in the context of emergent adult aquatic insects as prey subsidies to terrestrial consumers. This was demonstrated by Henschel et al. [9] where the abundances of emergent adult aquatic midges in riparian fields adjacent to a large river helped stimulate higher abundances of spiders and lower abundances of herbivorous leafhoppers, leading to a trophic cascade. The aquatic insects had a bottom-up effect on spiders and this subsidy facilitated a top-down effect that cascaded from spiders to leafhoppers to plants. The apparent competition motif becomes relevant because the aquatic midges exerted a negative indirect effect on leafhoppers mediated through their common arachnid predators.

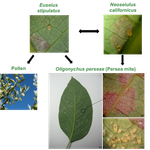

In the preprint “The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web” [6], the authors have described different permutations of a simple mite community present in avocado orchards (Persea americana). This community comprises of two predators (Euseius stipulatus and Neoseiulus californicus), one herbivore as shared prey (Oligonychus perseae), and pollen of Carpobrotus edulis as alternative food resource, with the potential for the intraguild predation and apparent competition interaction motifs to be expressed. The authors determined that these motifs should be realized based off pairwise feeding trials. It is common for food-web researchers to depict potential food webs, which contain all species sampled and all potential trophic links based on laboratory feeding trials (as demonstrated here) or from observational data and literature reviews [10]. In reality, not all these potential feeding links are realized because species may partition space and time, thus driving alternative food-web architectures. In “The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web” [6], the authors are able to show that placing species in combinations that should yield more complex interaction motifs based off pairwise feeding trials fails to deliver – the predators revert to their preferred prey resulting in modular and simple trophic chains to be expressed. Whilst these realized interaction motifs may be stable, there might also be a tradeoff with function by yielding less top-down control than desirable when considering the potential for ecosystem services such as pest management. These are valuable insights, although it should be noted that here the fundamental niche is described in a strictly Eltonian sense as a trophic role [11]. Adding additional niche dimensions (sensu [12]), such as a thermal gradient could alter the observed interactions, although it might be possible to explain these contingencies through metabolic and optimal foraging theory combined with species traits. Nonetheless, the results of these experiments further demonstrate the need for ecologists to cross-validate theory with empirical approaches to develop more realistic and predictive food-web models, lest they invoke the wrath of Gary Polis´ ghost by “trying to explain phenomena that do not exist”.

References

[1] Polis, G. A. (1991). Complex trophic interactions in deserts: an empirical critique of food-web theory. The American Naturalist, 138(1), 123-155. doi: 10.1086/285208

[2] May, R. M. (1973). Stability and complexity in model ecosystems. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA

[3] Dunne, J. A. (2006). The network structure of food webs. In Pascual, M., & Dunne, J. A. (eds) Ecological Networks: Linking Structure to Dynamics in Food Webs. Oxford University Press, New York, USA, 27-86

[4] Menge, B. A., & Sutherland, J. P. (1976). Species diversity gradients: synthesis of the roles of predation, competition, and temporal heterogeneity. The American Naturalist, 110(973), 351-369. doi: 10.1086/283073

[5] Paine, R. T. (1966). Food web complexity and species diversity. The American Naturalist, 100(910), 65-75. doi: 10.1086/282400

[6] Torres-Campos, I., Magalhães, S., Moya-Laraño, J., & Montserrat, M. (2018). The return of the trophic chain: fundamental vs realized interactions in a simple arthropod food web. bioRxiv, 324178, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecol. doi: 10.1101/324178

[7] Kéfi, S., Berlow, E. L., Wieters, E. A., Joppa, L. N., Wood, S. A., Brose, U., & Navarrete, S. A. (2015). Network structure beyond food webs: mapping non‐trophic and trophic interactions on Chilean rocky shores. Ecology, 96(1), 291-303. doi: 10.1890/13-1424.1

[8] Burdon, F. J., & Harding, J. S. (2008). The linkage between riparian predators and aquatic insects across a stream‐resource spectrum. Freshwater Biology, 53(2), 330-346. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01897.x

[9] Henschel, J. R., Mahsberg, D., & Stumpf, H. (2001). Allochthonous aquatic insects increase predation and decrease herbivory in river shore food webs. Oikos, 93(3), 429-438. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.930308.x

[10] Brose, U., Pavao-Zuckerman, M., Eklöf, A., Bengtsson, J., Berg, M. P., Cousins, S. H., Mulder, C., Verhoef, H. A., & Wolters, V. (2005). Spatial aspects of food webs. In de Ruiter, P., Wolters, V., Moore, J. C., & Melville-Smith, K. (eds) Dynamic Food Webs. vol 3. Academic Press, Burlington, 463-469

[11] Elton, C. (1927). Animal Ecology. Sidgwick and Jackson, London, UK

[12] Hutchinson, G. E. (1957). Concluding Remarks. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 22, 415-427. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1957.022.01.039

Review: 1

Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)

The promise and limits of DNA based approach to infer diet flexibility in endangered top predators

Recommended by Sophie Arnaud-Haond based on reviews by Francis John Burdon and Babett GüntherThere is growing evidence of worldwide decline of populations of top predators, including marine ones (Heithaus et al, 2008, Mc Cauley et al., 2015), with cascading effects expected at the ecosystem level, due to global change and human activities, including habitat loss or fragmentation, the collapse or the range shifts of their preys. On a global scale, seabirds are among the most threatened group of birds, about one-third of them being considered as threatened or endangered (Votier& Sherley, 2017). The large consequences of the decrease of the populations of preys they feed on (Cury et al, 2011) points diet flexibility as one important element to understand for effective management (McInnes et al, 2017). Nevertheless, morphological inventory of preys requires intrusive protocols, and the differential digestion rate of distinct taxa may lead to a large bias in morphological-based diet assessments. The use of DNA metabarcoding on feces (or diet DNA, dDNA) now allows non-invasive approaches facilitating the recollection of samples and the detection of multiple preys independently of their digestion rates (Deagle et al., 2019). Although no gold standard exists yet to avoid bias associated with metabarcoding (primer bias, gaps in reference databases, inability to differentiate primary from secondary predation…), the use of these recent techniques has already improved the knowledge of the foraging behaviour and diet of many animals (Ando et al., 2020).

Both promise and shortcomings of this approach are illustrated in the article “Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica)” by Quereteja et al. (2021). In this work, the authors assessed the nature and spatio-temporal flexibility of the foraging behaviour and consequent diet of the endangered petrel Procellaria westlandica from New-Zealand through metabarcoding of faeces samples.

The results of this dDNA, non-invasive approach, identify some expected and also unexpected prey items, some of which require further investigation likely due to large gaps in the reference databases. They also reveal the temporal (before and after hatching) and spatial (across colonies only 1.5km apart) flexibility of the foraging behaviour, additionally suggesting a possible influence of fisheries activities in the surroundings of the colonies. This study thus both underlines the power of the non-invasive metabarcoding approach on faeces, and the important results such analysis can deliver for conservation, pointing a potential for diet flexibility that may be essential for the resilience of this iconic yet endangered species.

References

Ando H, Mukai H, Komura T, Dewi T, Ando M, Isagi Y (2020) Methodological trends and perspectives of animal dietary studies by noninvasive fecal DNA metabarcoding. Environmental DNA, 2, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn3.117

Cury PM, Boyd IL, Bonhommeau S, Anker-Nilssen T, Crawford RJM, Furness RW, Mills JA, Murphy EJ, Österblom H, Paleczny M, Piatt JF, Roux J-P, Shannon L, Sydeman WJ (2011) Global Seabird Response to Forage Fish Depletion—One-Third for the Birds. Science, 334, 1703–1706. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1212928

Deagle BE, Thomas AC, McInnes JC, Clarke LJ, Vesterinen EJ, Clare EL, Kartzinel TR, Eveson JP (2019) Counting with DNA in metabarcoding studies: How should we convert sequence reads to dietary data? Molecular Ecology, 28, 391–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.14734

Heithaus MR, Frid A, Wirsing AJ, Worm B (2008) Predicting ecological consequences of marine top predator declines. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 23, 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.003

McCauley DJ, Pinsky ML, Palumbi SR, Estes JA, Joyce FH, Warner RR (2015) Marine defaunation: Animal loss in the global ocean. Science, 347, 1255641. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255641

McInnes JC, Jarman SN, Lea M-A, Raymond B, Deagle BE, Phillips RA, Catry P, Stanworth A, Weimerskirch H, Kusch A, Gras M, Cherel Y, Maschette D, Alderman R (2017) DNA Metabarcoding as a Marine Conservation and Management Tool: A Circumpolar Examination of Fishery Discards in the Diet of Threatened Albatrosses. Frontiers in Marine Science, 4, 277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00277

Querejeta M, Lefort M-C, Bretagnolle V, Boyer S (2021) Metabarcoding faecal samples to investigate spatiotemporal variation in the diet of the endangered Westland petrel (Procellaria westlandica). bioRxiv, 2020.10.30.360289, ver. 4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.360289

Votier SC, Sherley RB (2017) Seabirds. Current Biology, 27, R448–R450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.042