Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract▲ | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

15 Jul 2023

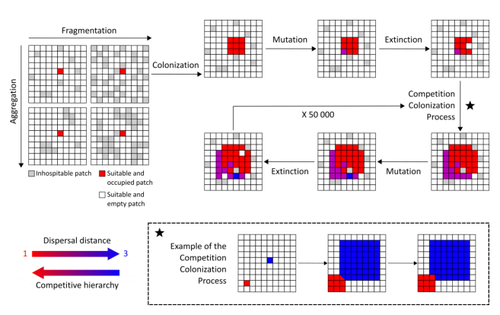

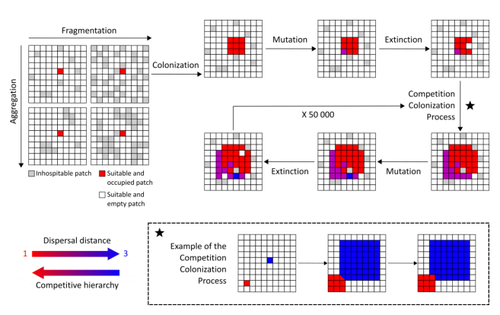

Evolution of dispersal and the maintenance of fragmented metapopulationsBasile Finand, Thibaud Monnin, Nicolas Loeuille https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.08.495260The spatial dynamics of habitat fragmentation drives the evolution of dispersal and metapopulation persistenceRecommended by Frédéric Guichard based on reviews by Eva Kisdi, David Murray-Stoker, Shripad Tuljapurkar and 1 anonymous reviewerThe persistence of populations facing the destruction of their habitat is a multifaceted question that has mobilized theoreticians and empiricists alike for decades. As an ecological question, persistence has been studied as the spatial rescue of populations via dispersal into remaining suitable habitats. The spatial aggregation of habitat destruction has been a key component of these studies, and it has been applied to the problem of coexistence by integrating competition-colonization tradeoffs. There is a rich ecological literature on this topic, both from theoretical and field studies (Fahrig 2003). The relationship between life-history strategies of species and their resilience to spatially structured habitat fragmentation is also an important component of conservation strategies through the management of land use, networks of protected areas, and the creation of corridors. In the context of environmental change, the ability of species to adapt to changes in landscape configuration and availability can be treated as an eco-evolutionary process by considering the possibility of evolutionary rescue (Heino and Hanski 2001; Bell 2017). However, eco-evolutionary dynamics considering spatially structured changes in landscapes and life-history tradeoffs remains an outstanding question. Finand et al. (2023) formulate the problem of persistence in fragmented landscapes over evolutionary time scales by studying models for the evolution of dispersal in relation to habitat fragmentation and spatial aggregation. Their simulations were conducted on a spatial grid where individuals can colonize suitable patch as a function of their competitive rank that decreases as a function of their (ii) dispersal distance trait. Simulations were run under fixed habitat fragmentation (proportion of unsuitable habitat) and aggregation, and with an explicit rate of habitat destruction to study evolutionary rescue. Their results reveal a balance between the selection for high dispersal under increasing habitat fragmentation and selection for lower dispersal in response to habitat aggregation. This balance leads to the coexistence of polymorphic dispersal strategies in highly aggregated landscapes with low fragmentation where high dispersers inhabit aggregated habitats while low dispersers are found in isolated habitats. The authors then integrate the spatial rescue mechanism to the problem of evolutionary rescue in response to temporally increasing fragmentation. There they show how rapid evolution allows for evolutionary rescue through the evolution of high dispersal. They also show the limits to this evolutionary rescue to cases where both aggregation and fragmentation are not too high. Interestingly, habitat aggregation prevents evolutionary rescue by directly affecting the evolutionary potential of dispersal. The study is based on simple scenarios that ignore the complexity of relationships between dispersal, landscape properties, and species interactions. This simplicity is the strength of the study, revealing basic mechanisms that can now be tested against other life-history tradeoffs and species interactions. Finand et al. (2023) provide a novel foundation for the study of eco-evolutionary dynamics in metacommunities exposed to spatially structured habitat destruction. They point to important assumptions that must be made along the way, including the relationships between dispersal distance and fecundity (they assume a positive relationship), and the nature of life-history tradeoffs between dispersal rate and local competitive abilities.

Bell, G. 2017. Evolutionary Rescue. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 48:605–627. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-023011 | Evolution of dispersal and the maintenance of fragmented metapopulations | Basile Finand, Thibaud Monnin, Nicolas Loeuille | <p>Because it affects dispersal risk and modifies competition levels, habitat fragmentation directly constrains dispersal evolution. When dispersal is traded-off against competitive ability, increased fragmentation is often expected to select high... |  | Colonization, Competition, Dispersal & Migration, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Frédéric Guichard | 2022-06-10 13:51:15 | View | |

30 Mar 2021

Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed gracklesBlaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6sFrom cognition to range dynamics – and from preregistration to peer-reviewed preprintRecommended by Emanuel A. Fronhofer based on reviews by Laure Cauchard and 1 anonymous reviewerIn 2018 Blaisdell and colleagues set out to study how causal cognition may impact large scale macroecological patterns, more specifically range dynamics, in the great-tailed grackle (Fronhofer 2019). This line of research is at the forefront of current thought in macroecology, a field that has started to recognize the importance of animal behaviour more generally (see e.g. Keith and Bull (2017)). Importantly, the authors were pioneering the use of preregistrations in ecology and evolution with the aim of improving the quality of academic research. Now, nearly 3 years later, it is thanks to their endeavour of making research better that we learn that the authors are “[...] unable to speculate about the potential role of causal cognition in a species that is rapidly expanding its geographic range.” (Blaisdell et al. 2021; page 2). Is this a success or a failure? Every reader will have to find an answer to this question individually and there will certainly be variation in these answers as becomes clear from the referees’ comments. In my opinion, this is a success story of a more stringent and transparent approach to doing research which will help us move forward, both methodologically and conceptually. References Fronhofer (2019) From cognition to range dynamics: advancing our understanding of macroe- Keith, S. A. and Bull, J. W. (2017) Animal culture impacts species' capacity to realise climate-driven range shifts. Ecography, 40: 296-304. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02481 Blaisdell, A., Seitz, B., Rowney, C., Folsom, M., MacPherson, M., Deffner, D., and Logan, C. J. (2021) Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles. PsyArXiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer community in Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/z4p6s | Do the more flexible individuals rely more on causal cognition? Observation versus intervention in causal inference in great-tailed grackles | Blaisdell A, Seitz B, Rowney C, Folsom M, MacPherson M, Deffner D, Logan CJ | <p>Behavioral flexibility, the ability to change behavior when circumstances change based on learning from previous experience, is thought to play an important role in a species’ ability to successfully adapt to new environments and expand its geo... | Preregistrations | Emanuel A. Fronhofer | 2020-11-27 09:49:55 | View | ||

10 Jan 2019

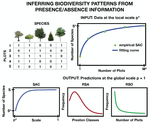

Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrencesAnna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan https://doi.org/10.1101/387456Upscaling the neighborhood: how to get species diversity, abundance and range distributions from local presence/absence dataRecommended by Matthieu Barbier based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and 1 anonymous reviewer

How do you estimate the biodiversity of a whole community, or the distribution of abundances and ranges of its species, from presence/absence data in scattered samples? ADDITIONAL COMMENTS 1) To explain the novelty of the authors' contribution, it is useful to look at competing techniques. 2) The main condition for all such approaches to work is well-mixedness: each sample should be sufficiently like a lot drawn from the same skewed lottery. As long as that condition applies, finding the best approach is a theoretical matter of probabilities and combinatorics that may, in time, be given a definite answer. 3) One may ask: why the Negative Binomial as a Species Abundance Distribution? References [1] Fisher, R. A., Corbet, A. S., & Williams, C. B. (1943). The relation between the number of species and the number of individuals in a random sample of an animal population. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 42-58. doi: 10.2307/1411 | Inferring macro-ecological patterns from local species' occurrences | Anna Tovo, Marco Formentin, Samir Suweis, Samuele Stivanello, Sandro Azaele, Amos Maritan | <p>Biodiversity provides support for life, vital provisions, regulating services and has positive cultural impacts. It is therefore important to have accurate methods to measure biodiversity, in order to safeguard it when we discover it to be thre... |  | Macroecology, Species distributions, Statistical ecology, Theoretical ecology | Matthieu Barbier | 2018-08-09 16:44:09 | View | |

11 Aug 2023

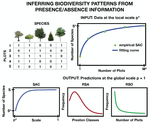

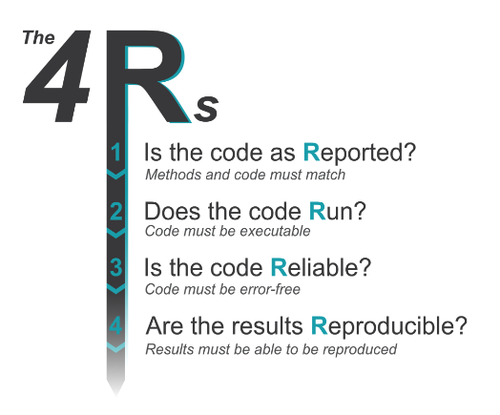

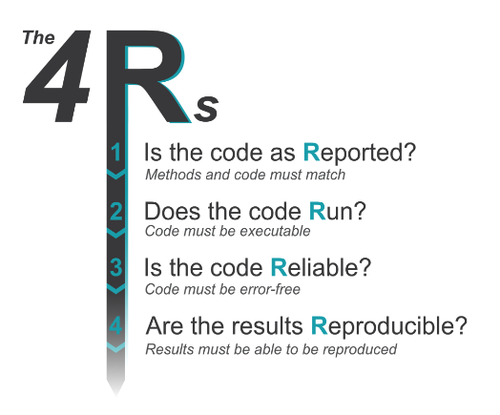

Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary BiologyEdward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64A handy “How to” review code for ecologists and evolutionary biologistsRecommended by Corina Logan based on reviews by Serena Caplins and 1 anonymous reviewerIvimey Cook et al. (2023) provide a concise and useful “How to” review code for researchers in the fields of ecology and evolutionary biology, where the systematic review of code is not yet standard practice during the peer review of articles. Consequently, this article is full of tips for authors on how to make their code easier to review. This handy article applies not only to ecology and evolutionary biology, but to many fields that are learning how to make code more reproducible and shareable. Taking this step toward transparency is key to improving research rigor (Brito et al. 2020) and is a necessary step in helping make research trustable by the public (Rosman et al. 2022). References Brito, J. J., Li, J., Moore, J. H., Greene, C. S., Nogoy, N. A., Garmire, L. X., & Mangul, S. (2020). Recommendations to enhance rigor and reproducibility in biomedical research. GigaScience, 9(6), giaa056. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giaa056 Ivimey-Cook, E. R., Pick, J. L., Bairos-Novak, K., Culina, A., Gould, E., Grainger, M., Marshall, B., Moreau, D., Paquet, M., Royauté, R., Sanchez-Tojar, A., Silva, I., Windecker, S. (2023). Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. EcoEvoRxiv, ver 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2CG64 Rosman, T., Bosnjak, M., Silber, H., Koßmann, J., & Heycke, T. (2022). Open science and public trust in science: Results from two studies. Public Understanding of Science, 31(8), 1046-1062. https://doi.org/10.1177/09636625221100686 | Implementing Code Review in the Scientific Workflow: Insights from Ecology and Evolutionary Biology | Edward Ivimey-Cook, Joel Pick, Kevin Bairos-Novak, Antica Culina, Elliot Gould, Matthew Grainger, Benjamin Marshall, David Moreau, Matthieu Paquet, Raphaël Royauté, Alfredo Sanchez-Tojar, Inês Silva, Saras Windecker | <p>Code review increases reliability and improves reproducibility of research. As such, code review is an inevitable step in software development and is common in fields such as computer science. However, despite its importance, code review is not... |  | Meta-analyses, Statistical ecology | Corina Logan | 2023-05-19 15:54:01 | View | |

22 Mar 2021

Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore speciesBastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544Plants preserve the ghost of competition past for herbivores, but mothers don’t careRecommended by Sara Magalhães based on reviews by Inês Fragata and Raul Costa-PereiraSome biological hypotheses are widely popular, so much so that we tend to forget their original lack of success. This is particularly true for hypotheses with catchy names. The ‘Ghost of competition past’ is part of the title of a paper by the great ecologist, JH Connell, one of the many losses of 2020 (Connell 1980). The hypothesis states that, even though we may not detect competition in current populations, their traits and distributions may be shaped by past competition events. Although this hypothesis has known a great success in the ecological literature, the original paper actually ends with “I will no longer be persuaded by such invoking of "the Ghost of Competition Past"”. Similarly, the hypothesis that mothers of herbivores choose host plants where their offspring will have a higher fitness was proposed by John Jaenike in 1978 (Jaenike 1978), and later coined the ‘mother knows best’ hypothesis. The hypothesis was readily questioned or dismissed: “Mother doesn't know best” (Courtney and Kibota 1990), or “Does mother know best?” (Valladares and Lawton 1991), but remains widely popular. It thus seems that catchy names (and the intuitive ideas behind them) have a heuristic value that is independent from the original persuasion in these ideas and the accumulation of evidence that followed it. The paper by Castagneryol et al. (2021) analyses the preference-performance relationship in the box tree moth (BTM) Cydalima perspectalis, after defoliation of their host plant, the box tree, by conspecifics. It thus has bearings on the two previously mentioned hypotheses. Specifically, they created an artificial population of potted box trees in a greenhouse, in which 60 trees were infested with BTM third instar larvae, whereas 61 were left uninfested. One week later, these larvae were removed and another three weeks later, they released adult BTM females and recorded their host choice by counting egg clutches laid by these females on the plants. Finally, they evaluated the effect of previously infested vs uninfested plants on BTM performance by measuring the weight of third instar larvae that had emerged from those eggs. This experimental design was adopted because BTM is a multivoltine species. When the second generation of BTM arrives, plants have been defoliated by the first generation and did not fully recover. Indeed, Castagneryol et al. (2021) found that larvae that developed on previously infested plants were much smaller than those developing on uninfested plants, and the same was true for the chrysalis that emerged from those larvae. This provides unequivocal evidence for the existence of a ghost of competition past in this system. However, the existence of this ghost still does not result in a change in the distribution of BTM, precisely because mothers do not know best: they lay as many eggs on plants previously infested than on uninfested plants. The demonstration that the previous presence of a competitor affects the performance of this herbivore species confirms that ghosts exist. However, whether this entails that previous (interspecific) competition shapes species distributions, as originally meant, remains an open question. Species phenology may play an important role in exposing organisms to the ghost, as this time-lagged competition may have been often overlooked. It is also relevant to try to understand why mothers don’t care in this, and other systems. One possibility is that they will have few opportunities to effectively choose in the real world, due to limited dispersal or to all plants being previously infested. References Castagneyrol, B., Halder, I. van, Kadiri, Y., Schillé, L. and Jactel, H. (2021) Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species. bioRxiv, 2020.07.30.228544, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.30.228544 Connell, J. H. (1980). Diversity and the coevolution of competitors, or the ghost of competition past. Oikos, 131-138. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3544421 Courtney, S. P. and Kibota, T. T. (1990) in Insect-plant interactions (ed. Bernays, E.A.) 285-330. Jaenike, J. (1978). On optimal oviposition behavior in phytophagous insects. Theoretical population biology, 14(3), 350-356. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(78)90012-6 Valladares, G., and Lawton, J. H. (1991). Host-plant selection in the holly leaf-miner: does mother know best?. The Journal of Animal Ecology, 227-240. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/5456

| Host-mediated, cross-generational intraspecific competition in a herbivore species | Bastien Castagneyrol, Inge van Halder, Yasmine Kadiri, Laura Schillé, Hervé Jactel | <p>Conspecific insect herbivores co-occurring on the same host plant interact both directly through interference competition and indirectly through exploitative competition, plant-mediated interactions and enemy-mediated interactions. However, the... |  | Competition, Herbivory, Zoology | Sara Magalhães | 2020-08-03 15:50:23 | View | |

07 Aug 2023

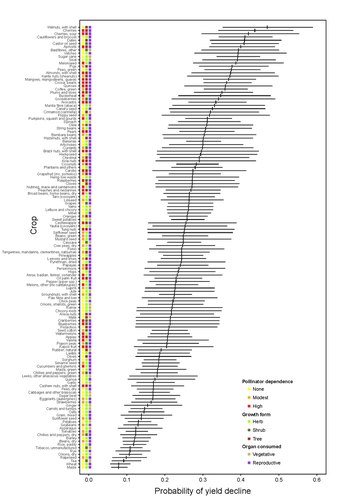

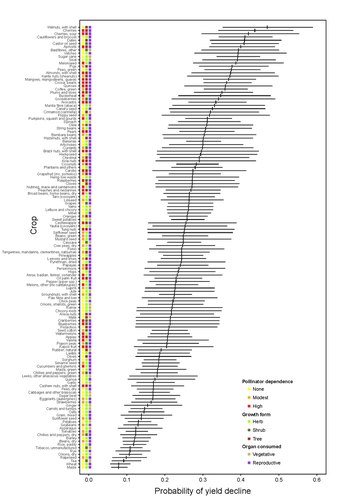

Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependenceMarcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617The complexities of understanding why yield is decliningRecommended by Ignasi Bartomeus based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Nicolas Deguines and 1 anonymous reviewer

Despite the repeated mantra that "correlation does not imply causation", ecological studies not amenable to experimental settings often rely on correlational patterns to infer the causes of observed patterns. In this context, it's of paramount importance to build a plausible hypothesis and take into account potential confounding factors. The paper by Aizen and collaborators (2023) is a beautiful example of how properly unveil the complexities of an intriguing pattern: The decline in yield of some crops over the last few decades. This is an outstanding question to solve given the need to feed a growing population without destroying the environment, for example by increasing the area under cultivation. Previous studies suggested that pollinator-dependent crops were more susceptible to suffering yield declines than non-pollinator-dependent crops (Garibaldi et al 2011). Given the actual population declines of some pollinators, especially in agricultural areas, this correlative evidence was quite appealing to be interpreted as a causal effect. However, as elegantly shown by Aizen and colleagues in this paper, this first analysis did not account for other alternative explanations, such as the effect of climate change on other plant life-history traits correlated with pollinator dependence. Plant life-history traits do not vary independently. For example, trees are more likely to be pollinator-dependent than herbs (Lanuza et al 2023), which can be an important confounding factor in the analysis. With an elegant analysis and an impressive global dataset, this paper shows that the declining trend in the yield of some crops is most likely associated with their life form than with their dependence on pollinators. This does not imply that pollinators are not important for crop yield, but that the decline in their populations is not leaving a clear imprint in the global yield production trends once accounted for the technological and agronomic improvements. All in all, this paper makes a key contribution to food security by elucidating the factors beyond declining yield trends, and is a brave example of how science can self-correct itself as new knowledge emerges. References Aizen, M.A., Gleiser, G., Kitzberger T. and Milla R. 2023. Being A Tree Crop Increases the Odds of Experiencing Yield Declines Irrespective of Pollinator Dependence. bioRxiv, 2023.04.27.538617, ver 2, peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538617 Lanuza, J.B., Rader, R., Stavert, J., Kendall, L.K., Saunders, M.E. and Bartomeus, I. 2023. Covariation among reproductive traits in flowering plants shapes their interactions with pollinators. Functional Ecology 37: 2072-2084. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.14340 Garibaldi, L.A., Aizen, M.A., Klein, A.M., Cunningham, S.A. and Harder, L.D. 2011. Global growth and stability of agricultural yield decrease with pollinator dependence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108: 5909-5914. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1012431108 | Being a tree crop increases the odds of experiencing yield declines irrespective of pollinator dependence | Marcelo A. Aizen, Gabriela Gleiser, Thomas Kitzberger, and Rubén Milla | <p>Crop yields, i.e., harvestable production per unit of cropland area, are in decline for a number of crops and regions, but the drivers of this process are poorly known. Global decreases in pollinator abundance and diversity have been proposed a... |  | Agroecology, Climate change, Community ecology, Demography, Facilitation & Mutualism, Life history, Phenotypic plasticity, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Ignasi Bartomeus | 2023-05-02 18:54:44 | View | |

23 Jan 2024

Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmlandCharlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.07.27.550774The importance of managing linear features in agricultural landscapes for farmland birdsRecommended by Ricardo Correia based on reviews by Matthew Grainger and 1 anonymous reviewerEuropean farmland bird populations continue declining at an alarming rate, and some species require urgent action to avoid their demise (Silva et al. 2024). While factors such as climate change and urbanization also play an important role in driving the decline of farmland bird populations, its main driver seems to be linked with agricultural intensification (Rigal et al. 2023). Besides increased pesticide and fertilizer use, agricultural intensification often results in the homogenization of agricultural landscapes through the removal of seminatural linear features such as hedgerows, field margins, and grassy strips that can be beneficial for biodiversity. These features may be particularly important during the breeding season, when breeding farmland birds can benefit from patches of denser vegetation to conceal nests and improve breeding success. It is both important and timely to understand how landscape management can help to address the ongoing decline of farmland birds by identifying specific actions that can boost breeding success. Perrot et al. 2023 contribute to this effort by exploring how red-legged partridges use linear features in an intensive agricultural landscape during the breeding season. Through a combination of targeted fieldwork and GPS tracking, the authors highlight patterns in home range size and habitat selection that provide insights for landscape management. Specifically, their results suggest that birds have smaller range sizes in the vicinity of traffic routes and seminatural features structured by both herbaceous and woody cover. Furthermore, they show that breeding birds tend to choose linear elements with herbaceous cover whereas non-breeders prefer linear elements with woody cover, underlining the importance of accounting for the needs of both breeding and non-breeding birds. In particular, the authors stress the importance of providing additional vegetation elements such as hedges, grassy strips or embankments in order to increase landscape heterogeneity. These landscape elements are usually found in the vicinity of linear infrastructures such as roads and tracks, but it is important they are available also in separate areas to avoid the risk of bird collision and the authors provide specific recommendations towards this end. Overall, this is an important study with clear recommendations on how to improve landscape management for these farmland birds. References Perrot, C., Séranne, L., Berceaux, A., Noel, M., Arroyo, B., & Bacon, L. (2023) "Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland." bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. | Use of linear features by red-legged partridges in an intensive agricultural landscape: implications for landscape management in farmland | Charlotte Perrot, Antoine Berceaux, Mathias Noel, Beatriz Arroyo, Leo Bacon | <p>Current agricultural practices and change are the major cause of biodiversity loss. An important change associated with the intensification of agriculture in the last 50 years is the spatial homogenization of the landscape with substantial loss... |  | Agroecology, Behaviour & Ethology, Biodiversity, Conservation biology, Habitat selection | Ricardo Correia | 2023-08-01 10:27:33 | View | |

09 Dec 2019

Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive successAinhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus https://doi.org/10.1101/629931Improving our knowledge of species interaction networksRecommended by Cédric Gaucherel based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by Michael Lattorff, Nicolas Deguines and 3 anonymous reviewers

Ecosystems shelter a huge number of species, continuously interacting. Each species interact in various ways, with trophic interactions, but also non-trophic interactions, not mentioning the abiotic and anthropogenic interactions. In particular, pollination, competition, facilitation, parasitism and many other interaction types are simultaneously present at the same place in terrestrial ecosystems [1-2]. For this reason, we need today to improve our understanding of such complex interaction networks to later anticipate their responses. This program is a huge challenge facing ecologists and they today join their forces among experimentalists, theoreticians and modelers. While some of us struggle in theoretical and modeling dimensions [3-4], some others perform brilliant works to observe and/or experiment on the same ecological objects [5-6]. References [1] Campbell, C., Yang, S., Albert, R., and Shea, K. (2011). A network model for plant–pollinator community assembly. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(1), 197-202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008204108 | Niche complementarity among pollinators increases community-level plant reproductive success | Ainhoa Magrach, Francisco P. Molina, Ignasi Bartomeus | <p>Declines in pollinator diversity and abundance have been reported across different regions, with implications for the reproductive success of plant species. However, research has focused primarily on pairwise plant-pollinator interactions, larg... |  | Ecosystem functioning, Interaction networks, Pollination, Terrestrial ecology | Cédric Gaucherel | Nicolas Deguines | 2019-05-07 17:03:23 | View |

16 Jun 2023

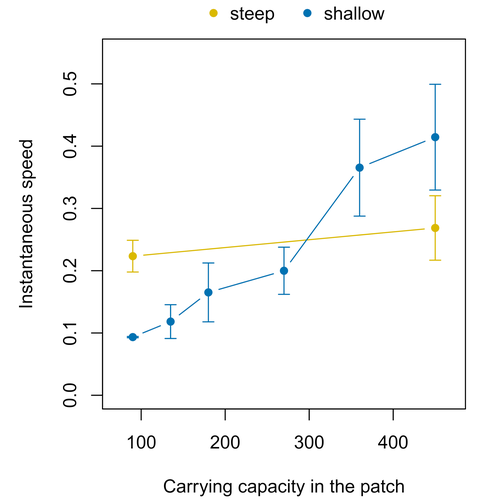

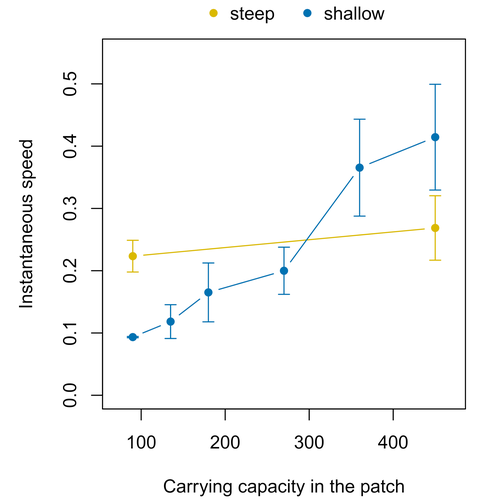

Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansionThibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255Combining stochastic models and experiments to understand dispersal in heterogeneous environmentsRecommended by Joaquín Hortal based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewersDispersal is a key element of the natural dynamics of meta-communities, and plays a central role in the success of populations colonizing new landscapes. Understanding how demographic processes may affect the speed at which alien species spread through environmentally-heterogeneous habitat fragments is therefore of key importance to manage biological invasions. This requires studying together the complex interplay of dispersal and population processes, two inextricably related phenomena that can produce many possible outcomes. Stochastic models offer an opportunity to describe this kind of process in a meaningful way, but to ensure that they are realistic (sensu Levins 1966) it is also necessary to combine model simulations with empirical data (Snäll et al. 2007). Morel-Journel et al. (2023) put together stochastic models and experimental data to study how population density may affect the speed at which alien species spread through a heterogeneous landscape. They do it by focusing on what they call ‘colonisation debt’, which is merely the impact that population density at the invasion front may have on the speed at which the species colonizes patches of different carrying capacities. They investigate this issue through two largely independent approaches. First, a stochastic model of dispersal throughout the patches of a linear, 1-dimensional landscape, which accounts for different degrees of density-dependent growth. And second, a microcosm experiment of a parasitoid wasp colonizing patches with different numbers of host eggs. In both cases, they compare the velocity of colonization of patches with lower or higher carrying capacity than the previous one (i.e. what they call upward or downward gradients). Their results show that density-dependent processes influence the speed at which new fragments are colonized is significantly reduced by positive density dependence. When either population growth or dispersal rate depend on density, colonisation debt limits the speed of invasion, which turns out to be dependent on the strength and direction of the gradient between the conditions of the invasion front, and the newly colonized patches. Although this result may be quite important to understand the meta-population dynamics of dispersing species, it is important to note that in their study the environmental differences between patches do not take into account eventual shifts in the scenopoetic conditions (i.e. the values of the environmental parameters to which species niches’ respond to; Hutchinson 1978, see also Soberón 2007). Rather, differences arise from variations in the carrying capacity of the patches that are consecutively invaded, both in the in silico and microcosm experiments. That is, they account for potential differences in the size or quality of the invaded fragments, but not on the costs of colonizing fragments with different environmental conditions, which may also determine invasion speed through niche-driven processes. This aspect can be of particular importance in biological invasions or under climate change-driven range shifts, when adaptation to new environments is often required (Sakai et al. 2001; Whitney & Gabler 2008; Hill et al. 2011). The expansion of geographical distribution ranges is the result of complex eco-evolutionary processes where meta-community dynamics and niche shifts interact in a novel physical space and/or environment (see, e.g., Mestre et al. 2020). Here, the invasibility of native communities is determined by niche variations and how similar are the traits of alien and native species (Hui et al. 2023). Within this context, density-dependent processes will build upon and heterogeneous matrix of native communities and environments (Tischendorf et al. 2005), to eventually determine invasion success. What the results of Morel-Journel et al. (2023) show is that, when the invader shows density dependence, the invasion process can be slowed down by variations in the carrying capacity of patches along the dispersal front. This can be particularly useful to manage biological invasions; ongoing invasions can be at least partially controlled by manipulating the size or quality of the patches that are most adequate to the invader, controlling host populations to reduce carrying capacity. But further, landscape manipulation of such kind could be used in a preventive way, to account in advance for the effects of the introduction of alien species for agricultural exploitation or biological control, thereby providing an additional safeguard to practices such as the introduction of parasitoids to control plagues. These practical aspects are certainly worth exploring further, together with a more explicit account of the influence of the abiotic conditions and the characteristics of the invaded communities on the success and speed of biological invasions. REFERENCES Hill, J.K., Griffiths, H.M. & Thomas, C.D. (2011) Climate change and evolutionary adaptations at species' range margins. Annual Review of Entomology, 56, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144746 Hui, C., Pyšek, P. & Richardson, D.M. (2023) Disentangling the relationships among abundance, invasiveness and invasibility in trait space. npj Biodiversity, 2, 13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44185-023-00019-1 Hutchinson, G.E. (1978) An introduction to population biology. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. Levins, R. (1966) The strategy of model building in population biology. American Scientist, 54, 421-431. Mestre, A., Poulin, R. & Hortal, J. (2020) A niche perspective on the range expansion of symbionts. Biological Reviews, 95, 491-516. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12574 Morel-Journel, T., Haond, M., Duan, L., Mailleret, L. & Vercken, E. (2023) Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion. bioRxiv, 2022.11.13.516255, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.11.13.516255 Snäll, T., B. O'Hara, R. & Arjas, E. (2007) A mathematical and statistical framework for modelling dispersal. Oikos, 116, 1037-1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0030-1299.2007.15604.x Sakai, A.K., Allendorf, F.W., Holt, J.S., Lodge, D.M., Molofsky, J., With, K.A., Baughman, S., Cabin, R.J., Cohen, J.E., Ellstrand, N.C., McCauley, D.E., O'Neil, P., Parker, I.M., Thompson, J.N. & Weller, S.G. (2001) The population biology of invasive species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 32, 305-332. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114037 Soberón, J. (2007) Grinnellian and Eltonian niches and geographic distributions of species. Ecology Letters, 10, 1115-1123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01107.x Tischendorf, L., Grez, A., Zaviezo, T. & Fahrig, L. (2005) Mechanisms affecting population density in fragmented habitat. Ecology and Society, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01265-100107 Whitney, K.D. & Gabler, C.A. (2008) Rapid evolution in introduced species, 'invasive traits' and recipient communities: challenges for predicting invasive potential. Diversity and Distributions, 14, 569-580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00473.x | Colonisation debt: when invasion history impacts current range expansion | Thibaut Morel-Journel, Marjorie Haond, Lana Duan, Ludovic Mailleret, Elodie Vercken | <p>Demographic processes that occur at the local level, such as positive density dependence in growth or dispersal, are known to shape population range expansion, notably by linking carrying capacity to invasion speed. As a result of these process... |  | Biological invasions, Colonization, Dispersal & Migration, Experimental ecology, Landscape ecology, Population ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Joaquín Hortal | Anonymous, Anonymous | 2022-11-16 15:52:08 | View |

27 May 2019

Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversityTadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino https://doi.org/10.1101/515098Toward an empirical synthesis on the niche versus stochastic debateRecommended by Eric Harvey based on reviews by Kevin Cazelles and Romain BertrandAs far back as Clements [1] and Gleason [2], the historical schism between deterministic and stochastic perspectives has divided ecologists. Deterministic theories tend to emphasize niche-based processes such as environmental filtering and species interactions as the main drivers of species distribution in nature, while stochastic theories mainly focus on chance colonization, random extinctions and ecological drift [3]. Although the old days when ecologists were fighting fiercely over null models and their adequacy to capture niche-based processes is over [4], the ghost of that debate between deterministic and stochastic perspectives came back to haunt ecologists in the form of the ‘environment versus space’ debate with the development of metacommunity theory [5]. While interest in that question led to meaningful syntheses of metacommunity dynamics in natural systems [6], it also illustrated how context-dependant the answer was [7]. One of the next frontiers in metacommunity ecology is to identify the underlying drivers of this observed context-dependency in the relative importance of ecological processus [7, 8]. References [1] Clements, F. E. (1936). Nature and structure of the climax. Journal of ecology, 24(1), 252-284. doi: 10.2307/2256278 | Community size affects the signals of ecological drift and selection on biodiversity | Tadeu Siqueira, Victor S. Saito, Luis M. Bini, Adriano S. Melo, Danielle K. Petsch, Victor L. Landeiro, Kimmo T. Tolonen, Jenny Jyrkänkallio-Mikkola, Janne Soininen, Jani Heino | <p>Ecological drift can override the effects of deterministic niche selection on small populations and drive the assembly of small communities. We tested the hypothesis that smaller local communities are more dissimilar among each other because of... | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Community ecology, Competition, Conservation biology, Dispersal & Migration, Freshwater ecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations | Eric Harvey | 2019-01-09 19:06:21 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle