Latest recommendations

| Id | Title | Authors | Abstract | Picture | Thematic fields | Recommender | Reviewers | Submission date▲ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

26 May 2023

Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibilityMcCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59KDo reversal learning methods measure behavioral flexibility?Recommended by Aurélie Coulon based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh based on reviews by Maxime Dahirel and Aparajitha Ramesh

Assessing the reliability of the methods we use in actually measuring the intended trait should be one of our first priorities when designing a study – especially when the trait in question is not directly observable and is measured through a proxy. This is the case for cognitive traits, which are often quantified through measures of behavioral performance. Behavioral flexibility is of particular interest in the context of great environmental changes that a lot of populations have to experiment. This type of behavioral performance is often measured through reversal learning experiments (Bond 2007). In these experiments, individuals first learn a preference, for example for an object of a certain type of form or color, associated with a reward such as food. The characteristics of the rewarded object then change, and the individuals hence have to learn these new characteristics (to get the reward). The time needed by the individual to make this change in preference has been considered a measure of behavioral flexibility. Although reversal learning experiments have been widely used, their construct validity to assess behavioral flexibility has not been thoroughly tested. This was the aim of McCune and collaborators' (2023) study, through the test of the repeatability of individual performance within and across contexts of reversal learning, in the great-tailed grackle. This manuscript presents a post-study of the preregistered study* (Logan et al. 2019) that was peer-reviewed and received an In Principle Recommendation for PCI Ecology (Coulon 2019; the initial preregistration was split into 3 post-studies).

The first hypothesis was tested by measuring the repeatability of the time needed by individuals to switch color preference in a color reversal learning task (colored tubes), over serial sessions of this task. The second one was tested by measuring the time needed by individuals to switch solutions, within 3 different contexts: (1) colored tubes, (2) plastic and (3) wooden multi-access boxes involving several ways to access food. Despite limited sample sizes, the results of these experiments suggest that there is both temporal and contextual repeatability of behavioral flexibility performance of great-tailed grackles, as measured by reversal learning experiments. Those results are a first indication of the construct validity of reversal learning experiments to assess behavioral flexibility. As highlighted by McCune and collaborators, it is now necessary to assess the discriminant validity of these experiments, i.e. checking that a different performance is obtained with tasks (experiments) that are supposed to measure different cognitive abilities. Coulon, A. (2019) Can context changes improve behavioral flexibility? Towards a better understanding of species adaptability to environmental changes. Peer Community in Ecology, 100019. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.ecology.100019 Logan, CJ, Lukas D, Bergeron L, Folsom M, & McCune, K. (2019). Is behavioral flexibility related to foraging and social behavior in a rapidly expanding species? In Principle Acceptance by PCI Ecology of the Version on 6 Aug 2019. http://corinalogan.com/Preregistrations/g_flexmanip.html McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ (2023) Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility. EcoEvoRxiv, ver. 5 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/X2R59K | Using repeatability of performance within and across contexts to validate measures of behavioral flexibility | McCune KB, Blaisdell AP, Johnson-Ulrich Z, Lukas D, MacPherson M, Seitz BM, Sevchik A, Logan CJ | <p style="text-align: justify;">Research into animal cognitive abilities is increasing quickly and often uses methods where behavioral performance on a task is assumed to represent variation in the underlying cognitive trait. However, because thes... | Behaviour & Ethology, Evolutionary ecology, Preregistrations, Zoology | Aurélie Coulon | 2022-08-15 20:56:42 | View | ||

24 Jan 2023

Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic driversOmar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739Alpine ecology and their dynamics under climate changeRecommended by Sergio Estay based on reviews by Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewerResearch about the effects of climate change on ecological communities has been abundant in the last decades. In particular, studies about the effects of climate change on mountain ecosystems have been key for understanding and communicating the consequences of this global phenomenon. Alpine regions show higher increases in warming in comparison to low-altitude ecosystems and this trend is likely to continue. This warming has caused reduced snowfall and/or changes in the duration of snow cover. For example, Notarnicola (2020) reported that 78% of the world’s mountain areas have experienced a snow cover decline since 2000. In the same vein, snow cover has decreased by 10% compared with snow coverage in the late 1960s (Walther et al., 2002) and snow cover duration has decreased at a rate of 5 days/decade (Choi et al., 2010). These changes have impacted the dynamics of high-altitude plant and animal populations. Some impacts are changes in the hibernation of animals, the length of the growing season for plants and the soil microbial composition (Chávez et al. 2021). Lenzi et al. (2023), give us an excellent study using long-term data on alpine amphibian populations. Authors show how climate change has impacted the reproductive phenology of Bufo bufo, especially the breeding season starts 30 days earlier than ~40 years ago. This earlier breeding is associated with the increasing temperatures and reduced snow cover in these alpine ecosystems. However, these changes did not occur in a linear trend but a marked acceleration was observed until mid-1990s with a later stabilization. Authors associated these nonlinear changes with complex interactions between the global trend of seasonal temperatures and site-specific conditions. Beyond the earlier breeding season, changes in phenology can have important impacts on the long-term viability of alpine populations. Complex interactions could involve positive and negative effects like harder environmental conditions for propagules, faster development of juveniles, or changes in predation pressure. This study opens new research opportunities and questions like the urgent assessment of the global impact of climate change on animal fitness. This study provides key information for the conservation of these populations. References Chávez RO, Briceño VF, Lastra JA, Harris-Pascal D, Estay SA (2021) Snow Cover and Snow Persistence Changes in the Mocho-Choshuenco Volcano (Southern Chile) Derived From 35 Years of Landsat Satellite Images. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.643850 Choi G, Robinson DA, Kang S (2010) Changing Northern Hemisphere Snow Seasons. Journal of Climate, 23, 5305–5310. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3644.1 Lenzi O, Grossenbacher K, Zumbach S, Lüscher B, Althaus S, Schmocker D, Recher H, Thoma M, Ozgul A, Schmidt BR (2022) Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers.bioRxiv, 2022.08.16.503739, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.16.503739 Notarnicola C (2020) Hotspots of snow cover changes in global mountain regions over 2000–2018. Remote Sensing of Environment, 243, 111781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rse.2020.111781 | Four decades of phenology in an alpine amphibian: trends, stasis, and climatic drivers | Omar Lenzi, Kurt Grossenbacher, Silvia Zumbach, Beatrice Luescher, Sarah Althaus, Daniela Schmocker, Helmut Recher, Marco Thoma, Arpat Ozgul, Benedikt R. Schmidt | <p style="text-align: justify;">Strong phenological shifts in response to changes in climatic conditions have been reported for many species, including amphibians, which are expected to breed earlier. Phenological shifts in breeding are observed i... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Zoology | Sergio Estay | Anonymous, Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-18 08:25:21 | View |

24 May 2023

Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approachLugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761When does seasonal reproduction evolve?Recommended by Tim Coulson based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Nigel Yoccoz and 1 anonymous reviewer

Have you ever wondered why some species breed seasonally while others do not? You might think it is all down to lattitude and the harshness of winters but it turns out it is quite a bit more complicated than that. A consequence of this is that climate change may result in the evolution of the degree of seasonal reproduction, with some species perhaps becoming less seasonal and others more so even in the same habitat. Burtschell et al. (2023) investigated how various factors influence seasonal breeding by building an individual-based model of a baboon population from which they calculated the degree of seasonality for the fittest reproductive strategy. They then altered key aspects of their model to examine how these changes impacted the degree of seasonality in the reproductive strategy. What they found is fascinating. The degree of seasonality in reproductive strategy is expected to increase with increased seasonality in the environment, decreased food availability, increased energy expenditure, and how predictable resource availability is. Interestingly, neither female cycle length nor extrinsic infant mortality influenced the degree of seasonality in reproduction. What this means in reality for seasonal species is more challenging to understand. Some environments appear to be becoming more seasonal yet less predictable, and some species appear to be altering their daily energy budgets in response to changing climate in quite complex ways. As with pretty much everything in biology, Burtschell et al.'s work reveals much nuance and complexity, and that predicting how species might alter their reproductive timing is fraught with challenges. The paper is very well written. With a simpler model it may have proven possible to achieve analytical solutions, but this is a very minor gripe. The reviewers were positive about the paper, and I have little doubt it will be well-cited. REFERENCES Burtschell L, Dezeure J, Huchard E, Godelle B (2023) Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, 2022.08.22.504761, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.08.22.504761 | Evolutionary determinants of reproductive seasonality: a theoretical approach | Lugdiwine Burtschell, Jules Dezeure, Elise Huchard, Bernard Godelle | <p style="text-align: justify;">Reproductive seasonality is a major adaptation to seasonal cycles and varies substantially among organisms. This variation, which was long thought to reflect a simple latitudinal gradient, remains poorly understood ... |  | Evolutionary ecology, Life history, Theoretical ecology | Tim Coulson | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-08-23 21:37:28 | View |

31 May 2023

Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibiansMatutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425Amphibians under scrutiny - When human-dominated landscape mosaics are not in full compliance with their ecological requirementsRecommended by Sandrine Charles based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer based on reviews by Peter Vermeiren and 1 anonymous reviewer

Among vertebrates, amphibians are one of the most diverse groups with more than 7,000 known species. Amphibians occupy various ecosystems, including forests, wetlands, and freshwater habitats. Amphibians are known to be highly sensitive to changes in their environment, particularly to water quality and habitat degradation, so that monitoring abundance of amphibian populations can provide early warning signs of ecosystem disturbances that may also affect other organisms including humans (Bishop et al., 2012). Accordingly, efforts in habitat preservation and sustainable land and water management are necessary to safeguard amphibian populations. In this context, Matutini et al. (2023) compared ecological requirements of amphibian species with the quality of agricultural landscape mosaics. Doing so, they identified critical gaps in existing conservation tools that include protected areas, green infrastructures, and inventoried sites. Matutini et al. (2023) focused on nine amphibian species in the Pays-de-la-Loire region where the landscape has been fashioned over the years by human activities. Three of the chosen amphibian species are living in a dense hedgerow mosaic landscape, while five others are more generalists. Matutini et al. (2023) established multi-species habitat suitability maps, together with their levels of confidence, by combining single species maps with a probabilistic stacking method at 500-m resolution. From these maps, habitats were classified in five categories, from not suitable to highly suitable. Then, the circuit theory was used to map the potential connections between each highly suitable patch at the regional scale. Finally, comparing suitability maps with existing conservation tools, Matutini et al. (2023) were able to assess their coverage and efficiency. Whatever their species status (endangered or not), Matutini et al. (2023) highlighted some discrepancies between the ecological requirements of amphibians in terms of habitat quality and the conservation tools of the landscape mosaic within which they are evolving. More specifically, Matutini et al. (2023) found that protected areas and inventoried sites covered only a small proportion of highly suitable habitats, while green infrastructures covered around 50% of the potential habitat for amphibian species. Such a lack of coverage and efficiency of protected areas brings to light that geographical sites with amphibian conservation challenges are known but not protected. Regarding the landscape fragmentation, Matutini et al. (2023) found that generalist amphibian species have a more homogeneous distribution of suitable habitats at the regional scale. They also identified two bottlenecks between two areas of suitable habitats, a situation that could prove critical to amphibian movements if amphibians were forced to change habitats to global change. In conclusion, Matutini et al. (2023) bring convincing arguments in support of land-use species-conservation planning based on a better consideration of human-dominated landscape mosaics in full compliance with ecological requirements of the species that inhabit the regions concerned. ReferencesBishop, P.J., Angulo, A., Lewis, J.P., Moore, R.D., Rabb, G.B., Moreno, G., 2012. The Amphibian Extinction Crisis - what will it take to put the action into the Amphibian Conservation Action Plan? Sapiens - Surveys and Perspectives Integrating Environment and Society 5, 1–16. http://journals.openedition.org/sapiens/1406 Matutini, F., Baudry, J., Fortin, M.-J., Pain, G., Pithon, J., 2023. Conservation networks do not match ecological requirements of amphibians. bioRxiv, ver. 3 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.18.500425 | Conservation networks do not match the ecological requirements of amphibians | Matutini Florence, Jacques Baudry, Marie-Josée Fortin, Guillaume Pain, Joséphine Pithon | <p style="text-align: justify;">1. Amphibians are among the most threatened taxa as they are highly sensitive to habitat degradation and fragmentation. They are considered as model species to evaluate habitats quality in agricultural landscapes. I... | Biodiversity, Biogeography, Human impact, Landscape ecology, Macroecology, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Species distributions, Terrestrial ecology | Sandrine Charles | 2022-09-20 14:40:03 | View | ||

28 Apr 2023

Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical floraJulien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127Pollination-herbivory by weevils claiming for recognition: the Cinderella among pollinatorsRecommended by Juan Arroyo based on reviews by Susan Kirmse, Carlos Eduardo Nunes and 2 anonymous reviewersSince Charles Darwin times, and probably earlier, naturalists have been eager to report the rarest pollinators being discovered, and this still happens even in recent times; e.g., increased evidence of lizards, cockroaches, crickets or earwigs as pollinators (Suetsugu 2018, Komamura et al. 2021, de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023), shifts to invasive animals as pollinators, including passerine birds and rats (Pattemore & Wilcove 2012), new amazing cases of mimicry in pollination, such as “bleeding” flowers that mimic wounded insects (Heiduk et al., 2023) or even the possibility that a tree frog is reported for the first time as a pollinator (de Oliveira-Nogueira et al. 2023). This is in part due to a natural curiosity of humans about rarity, which pervades into scientific insight (Gaston 1994). Among pollinators, the apparent rarity of some interaction types is sometimes a symptom of a lack of enough inquiry. This seems to be the case of weevil pollination, given that these insects are widely recognized as herbivores, particularly those that use plant parts to nurse their breed and never were thought they could act also as mutualists, pollinating the species they infest. This is known as a case of brood site pollination mutualism (BSPM), which also involves an antagonistic counterpart (herbivory) to which plants should face. This is the focus of the manuscript (Haran et al. 2023) we are recommending here. There is wide treatment of this kind of pollination in textbooks, albeit focused on yucca-yucca moth and fig-fig wasp interactions due to their extreme specialization (Pellmyr 2003, Kjellberg et al. 2005), and more recently accompanied by Caryophyllaceae-moth relationship (Kephart et al. 2006). Here we find a detailed review that shows that the most diverse BSPM, in terms of number of plant and pollinator species involved, is that of weevils in the tropics. The mechanism of BSPM does not involve a unique morphological syndrome, as it is mostly functional and thus highly dependent on insect biology (Fenster & al. 2004), whereas the flower phenotypes are highly divergent among species. Probably, the inconspicuous nature of the interaction, and the overwhelming role of weevils as seed predators, even as pests, are among the causes of the neglection of weevils as pollinators, as it could be in part the case of ants as pollinators (de Vega et al. 2014). The paper by Haran et al (2023) comes to break this point. Thus, the rarity of weevil pollination in former reports is not a consequence of an anecdotical nature of this interaction, even for the BSPM, according to the number of cases the authors are reporting, both in terms of plant and pollinator species involved. This review has a classical narrative format which involves a long text describing the natural history behind the cases. It is timely and fills the gap for this important pollination interaction for biodiversity and also for economic implications for fruit production of some crops. Former reviews have addressed related topics on BSPM but focused on other pollinators, such as those mentioned above. Besides, the review put much effort into the animal side of the interaction, which is not common in the pollination literature. Admittedly, the authors focus on the detailed description of some paradigmatic cases, and thereafter suggest that these can be more frequently reported in the future, based on varied evidence from morphology, natural history, ecology, and distribution of alleged partners. This procedure was common during the development of anthecology, an almost missing term for floral ecology (Baker 1983), relying on accumulative evidence based on detailed observations and experiments on flowers and pollinators. Currently, a quantitative approach based on the tools of macroecological/macroevolutionary analyses is more frequent in reviews. However, this approach requires a high amount of information on the natural history of the partnership, which allows for sound hypothesis testing. By accumulating this information, this approach allows the authors to pose specific questions and hypotheses which can be tested, particularly on the efficiency of the systems and their specialization degree for both the plants and the weevils, apparently higher for the latter. This will guarantee that this paper will be frequently cited by floral ecologists and evolutionary biologists and be included among the plethora of floral syndromes already described, currently based on more explicit functional grounds (Fenster et al. 2004). In part, this is one of the reasons why the sections focused on future prospects is so large in the review. I foresee that this mutualistic/antagonistic relationship will provide excellent study cases for the relative weight of these contrary interactions among the same partners and its relationship with pollination specialization-generalization and patterns of diversification in the plants and/or the weevils. As new studies are coming, it is possible that BSPM by weevils appears more common in non-tropical biogeographical regions. In fact, other BSPM are not so uncommon in other regions (Prieto-Benítez et al. 2017). In the future, it would be desirable an appropriate testing of the actual effect of phylogenetic niche conservatism, using well known and appropriately selected BSPM cases and robust phylogenies of both partners in the mutualism. Phylogenetic niche conservatism is a central assumption by the authors to report as many cases as possible in their review, and for that they used taxonomic relatedness. As sequence data and derived phylogenies for large numbers of vascular plant species are becoming more frequent (Jin & Quian 2022), I would recommend the authors to perform a comparative analysis using this phylogenetic information. At least, they have included information on phylogenetic relatedness of weevils involved in BSPM which allow some inferences on the multiple origins of this interaction. This is a good start to explore the drivers of these multiple origins through the lens of comparative biology. References Baker HG (1983) An Outline of the History of Anthecology, or Pollination Biology. In: L Real (ed). Pollination Biology. Academic Press. de-Oliveira-Nogueira CH, Souza UF, Machado TM, Figueiredo-de-Andrade CA, Mónico AT, Sazima I, Sazima M, Toledo LF (2023). Between fruits, flowers and nectar: The extraordinary diet of the frog Xenohyla truncate. Food Webs 35: e00281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fooweb.2023.e00281 Fenster CB W, Armbruster S, Wilson P, Dudash MR, Thomson JD (2004). Pollination syndromes and floral specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 35: 375–403. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132347 Gaston KJ (1994). What is rarity? In KJ Gaston (ed): Rarity. Population and Community Biology Series, vol 13. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-0701-3_1 Haran J, Kergoat GJ, Bruno, de Medeiros AS (2023) Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora. hal. 03780127, version 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.inrae.fr/hal-03780127 Heiduk A, Brake I, Shuttleworth A, Johnson SD (2023) ‘Bleeding’ flowers of Ceropegia gerrardii (Apocynaceae-Asclepiadoideae) mimic wounded insects to attract kleptoparasitic fly pollinators. New Phytologist. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.18888 Jin, Y., & Qian, H. (2022). V. PhyloMaker2: An updated and enlarged R package that can generate very large phylogenies for vascular plants. Plant Diversity, 44(4), 335-339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pld.2022.05.005 Kjellberg F, Jousselin E, Hossaert-Mckey M, Rasplus JY (2005). Biology, ecology, and evolution of fig-pollinating wasps (Chalcidoidea, Agaonidae). In: A. Raman et al (eds) Biology, ecology and evolution of gall-inducing arthropods 2, 539-572. Science Publishers, Enfield. Komamura R, Koyama K, Yamauchi T, Konno Y, Gu L (2021). Pollination contribution differs among insects visiting Cardiocrinum cordatum flowers. Forests 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12040452 Pattemore DE, Wilcove DS (2012) Invasive rats and recent colonist birds partially compensate for the loss of endemic New Zealand pollinators. Proc. R. Soc. B 279: 1597–1605. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.2036 Pellmyr O (2003) Yuccas, yucca moths, and coevolution: a review. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 90: 35-55. https://doi.org/10.2307/3298524 Prieto-Benítez S, Yela JL, Giménez-Benavides L (2017) Ten years of progress in the study of Hadena-Caryophyllaceae nursery pollination. A review in light of new Mediterranean data. Flora, 232, 63-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2017.02.004 Suetsugu K (2019) Social wasps, crickets and cockroaches contribute to pollination of the holoparasitic plant Mitrastemon yamamotoi (Mitrastemonaceae) in southern Japan. Plant Biology 21 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12889 | Most diverse, most neglected: weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea) are ubiquitous specialized brood-site pollinators of tropical flora | Julien Haran, Gael J. Kergoat, Bruno A. S. de Medeiros | <p style="text-align: justify;">In tropical environments, and especially tropical rainforests, a major part of pollination services is provided by diverse insect lineages. Unbeknownst to most, beetles, and more specifically hyperdiverse weevils (C... | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Pollination, Tropical ecology | Juan Arroyo | 2022-09-28 11:54:37 | View | ||

28 Dec 2022

Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouseCharlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512An experimental approach for understanding how terrestrial isopods respond to environmental stressorsRecommended by Aniruddha Belsare based on reviews by Aaron Yilmaz and Michael MorrisIn this article, the authors discuss the results of their study investigating the effects of heat stress and moisture stress on a terrestrial isopod Armadilldium vulgare, the common woodlouse [1]. Specifically, the authors have assessed how increased temperature or decreased moisture affects life history traits (such as growth, survival, and reproduction) as well as physiological traits (immune cell parameters and \( beta \)-galactosidase activity). This article quantitatively evaluates the effects of the two stressors on woodlouse. Terrestrial isopods like woodlouse are sensitive to thermal and moisture stress [2; 3] and are therefore good models to test hypotheses in global change biology and for monitoring ecosystem health. An important feature of this study is the combination of experimental, laboratory, and analytical techniques. Experiments were conducted under controlled conditions in the laboratory by modulating temperature and moisture, life history and physiological traits were measured/analyzed and then tested using models. Both stressors had negative impacts on survival and reproduction of woodlouse, and result in premature ageing. Although thermal stress did not affect survival, it slowed woodlouse growth. Moisture stress did not have a detectable effect on woodlouse growth but decreased survival and reproductive success. An important insight from this study is that effects of heat and moisture stressors on woodlouse are not necessarily linear, and experimental approaches can be used to better elucidate the mechanisms and understand how these organisms respond to environmental stress. This article is timely given the increasing attention on biological monitoring and ecosystem health. References: [1] Depeux C, Branger A, Moulignier T, Moreau J, Lemaître J-F, Dechaume-Moncharmont F-X, Laverre T, Pauhlac H, Gaillard J-M, Beltran-Bech S (2022) Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse. bioRxiv, 2022.09.26.509512., ver. 3 peer-reviewd and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.09.26.509512 [2] Warburg MR, Linsenmair KE, Bercovitz K (1984) The effect of climate on the distribution and abundance of isopods. In: Sutton SL, Holdich DM, editors. The Biology of Terrestrial Isopods. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 339–367. [3] Hassall M, Helden A, Goldson A, Grant A (2005) Ecotypic differentiation and phenotypic plasticity in reproductive traits of Armadillidium vulgare (Isopoda: Oniscidea). Oecologia 143: 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-004-1772-3 | Deleterious effects of thermal and water stresses on life history and physiology: a case study on woodlouse | Charlotte Depeux, Angele Branger, Theo Moulignier, Jérôme Moreau, Jean-Francois Lemaitre, Francois-Xavier Dechaume-Moncharmont, Tiffany Laverre, Hélène Paulhac, Jean-Michel Gaillard, Sophie Beltran-Bech | <p>We tested independently the influences of increasing temperature and decreasing moisture on life history and physiological traits in the arthropod <em>Armadillidium vulgare</em>. Both increasing temperature and decreasing moisture led individua... |  | Biodiversity, Evolutionary ecology, Experimental ecology, Life history, Physiology, Terrestrial ecology, Zoology | Aniruddha Belsare | 2022-09-28 13:13:47 | View | |

01 Oct 2023

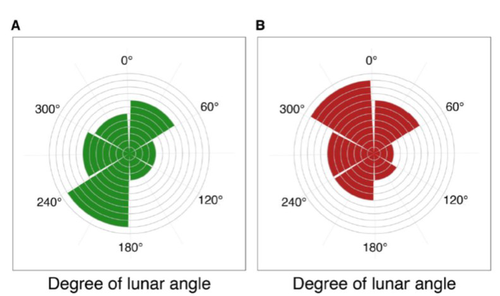

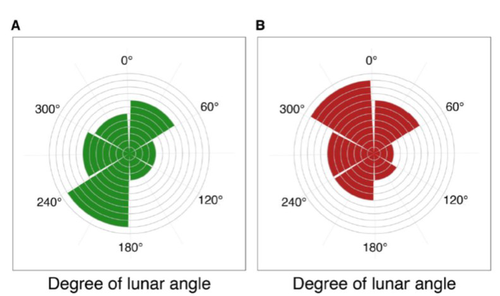

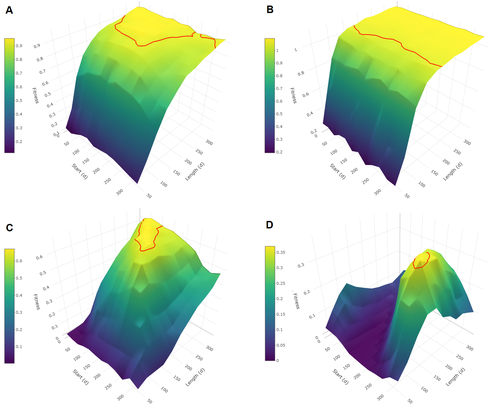

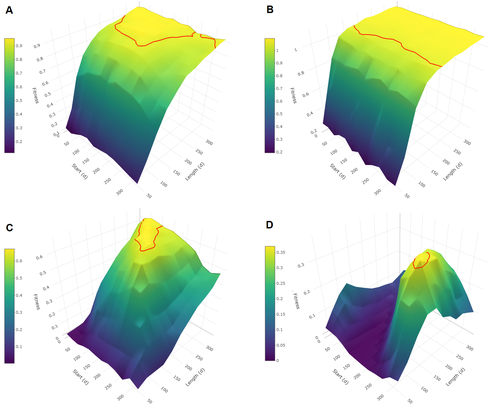

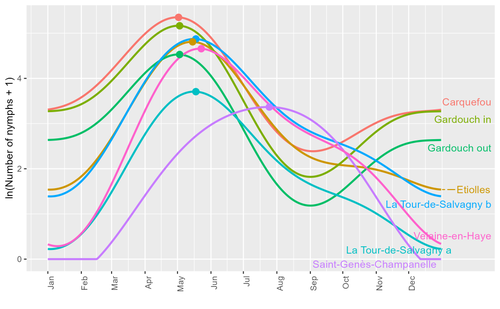

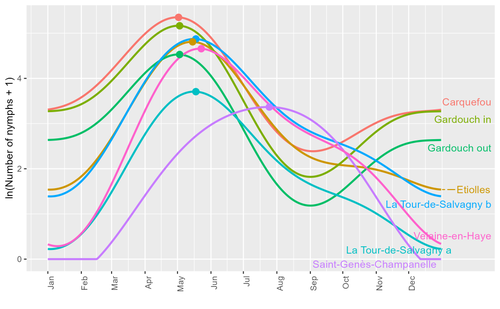

Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climateThierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Verheyden, Gwenaёl Vourc’h, Karine Chalvet-Monfray, Albert Agoulon https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416Assessing seasonality of tick abundance in different climatic regionsRecommended by Nigel Yoccoz based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers based on reviews by 2 anonymous reviewers

Tick-borne pathogens are considered as one of the major threats to public health – Lyme borreliosis being a well-known example of such disease. Global change – from climate change to changes in land use or invasive species – is playing a role in the increased risk associated with these pathogens. An important aspect of our knowledge of ticks and their associated pathogens is seasonality – one component being the phenology of within-year tick occurrences. This is important both in terms of health risk – e.g., when is the risk of encountering ticks high – and ecological understanding, as tick dynamics may depend on the weather as well as different hosts with their own dynamics and habitat use. Hoch et al. (2023) provide a detailed data set on the phenology of one species of tick, Ixodes ricinus, in 6 different locations of France. Whereas relatively cool sites showed a clear peak in spring-summer, warmer sites showed in addition relatively high occurrences in fall-winter, with a minimum in late summer-early fall. Such results add robust data to the existing evidence of the importance of local climatic patterns for explaining tick phenology. Recent analyses have shown that the phenology of Lyme borreliosis has been changing in northern Europe in the last 25 years, with seasonal peaks in cases occurring now 6 weeks earlier (Goren et al. 2023). The study by Hoch et al. (2023) is of too short duration to establish temporal changes in phenology (“only” 8 years, 2014-2021, see also Wongnak et al 2021 for some additional analyses; given the high year-to-year variability in weather, establishing phenological changes often require longer time series), and further work is needed to get better estimates of these changes and relate them to climate, land-use, and host density changes. Moreover, the phenology of ticks may also be related to species-specific tick phenology, and different tick species do not respond to current changes in identical ways (see for example differences between the two Ixodes species in Finland; Uusitalo et al. 2022). An efficient surveillance system requires therefore an adaptive monitoring design with regard to the tick species as well as the evolving causes of changes. References Goren, A., Viljugrein, H., Rivrud, I. M., Jore, S., Bakka, H., Vindenes, Y., & Mysterud, A. (2023). The emergence and shift in seasonality of Lyme borreliosis in Northern Europe. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 290(1993), 20222420. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2022.2420 Hoch, T., Madouasse, A., Jacquot, M., Wongnak, P., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Agoulon, A. (2023). Seasonality of host-seeking Ixodes ricinus nymph abundance in relation to climate. bioRxiv, ver.4 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.07.25.501416 Uusitalo, R., Siljander, M., Lindén, A., Sormunen, J. J., Aalto, J., Hendrickx, G., . . . Vapalahti, O. (2022). Predicting habitat suitability for Ixodes ricinus and Ixodes persulcatus ticks in Finland. Parasites & Vectors, 15(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05410-8 Wongnak, P., Bord, S., Jacquot, M., Agoulon, A., Beugnet, F., Bournez, L., . . . Chalvet-Monfray, K. (2022). Meteorological and climatic variables predict the phenology of Ixodes ricinus nymph activity in France, accounting for habitat heterogeneity. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7833. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11479-z | Seasonality of host-seeking *Ixodes ricinus* nymph abundance in relation to climate | Thierry Hoch, Aurélien Madouasse, Maude Jacquot, Phrutsamon Wongnak, Fréderic Beugnet, Laure Bournez, Jean-François Cosson, Frédéric Huard, Sara Moutailler, Olivier Plantard, Valérie Poux, Magalie René-Martellet, Muriel Vayssier-Taussat, Hélène Ve... | <p style="text-align: justify;">There is growing concern about climate change and its impact on human health. Specifically, global warming could increase the probability of emerging infectious diseases, notably because of changes in the geographic... |  | Climate change, Population ecology, Statistical ecology | Nigel Yoccoz | 2022-10-14 18:43:56 | View | |

29 May 2023

Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean SeaValentin Lauret, Hélène Labach, Léa David, Matthieu Authier, Olivier Gimenez https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/npd6uMapping co-occurence of human activities and wildlife from multiple data sourcesRecommended by Paul Caplat based on reviews by Mason Fidino and 1 anonymous reviewerTwo fields of research have grown considerably over the past twenty years: the investigation of human-wildlife conflicts (e.g. see Treves & Santiago-Ávila 2020), and multispecies occupancy modelling (Devarajan et al. 2020). In their recent study, Lauret et al. (2023) combined both in an elegant methodological framework, applied to the study of the co-occurrence of fishing activities and bottlenose dolphins in the French Mediterranean. A common issue with human-wildlife conflicts (and, in particular, fishery by-catch) is that data is often only available from those conflicts or interactions, limiting the validity of the predictions (Kuiper et al. 2022). Lauret et al. use independent data sources informing the occurrence of fishing vessels and dolphins, combined in a Bayesian multispecies occupancy model where vessels are "the other species". I particularly enjoyed that approach, as integration of human activities in ecological models can be extremely complex, but can also translate in phenomena that can be captured as one would of individuals of a species, as long as the assumptions are made clearly. Here, the model is made more interesting by accounting for environmental factors (seabed depth) borrowing an approach from Generalized Additive Models in the Bayesian framework. While not pretending to provide (yet) practical recommendations to help conserve bottlenose dolphins (and other wildlife conflicts), this study and the associated code are a promising step in that direction. REFERENCES Devarajan, K., Morelli, T.L. & Tenan, S. (2020), Multi-species occupancy models: review, roadmap, and recommendations. Ecography, 43: 1612-1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.04957 Kuiper, T., Loveridge, A.J. and Macdonald, D.W. (2022), Robust mapping of human–wildlife conflict: controlling for livestock distribution in carnivore depredation models. Anim. Conserv., 25: 195-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12730 Lauret V, Labach H, David L, Authier M, & Gimenez O (2023) Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean Sea. Ecoevoarxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by PCI Ecology. https://doi.org/10.32942/osf.io/npd6u Treves, A. & Santiago-Ávila, F.J. (2020). Myths and assumptions about human-wildlife conflict and coexistence. Conserv. Biol. 34, 811–818. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13472 | Using integrated multispecies occupancy models to map co-occurrence between bottlenose dolphins and fisheries in the Gulf of Lion, French Mediterranean Sea | Valentin Lauret, Hélène Labach, Léa David, Matthieu Authier, Olivier Gimenez | <p style="text-align: justify;">In the Mediterranean Sea, interactions between marine species and human activities are prevalent. The coastal distribution of bottlenose dolphins (<em>Tursiops truncatus</em>) and the predation pressure they put on ... |  | Marine ecology, Population ecology, Species distributions | Paul Caplat | 2022-10-21 11:13:36 | View | |

06 Nov 2023

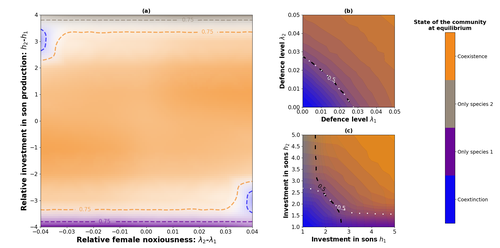

Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approachMaxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153Mullerian and Batesian mimicry can influence population and community dynamicsRecommended by Amanda Franklin based on reviews by Jesus Bellver and 1 anonymous reviewerMimicry between species has long attracted the attention of scientists. Over a century ago, Bates first proposed that palatable species should gain a benefit by resembling unpalatable species (Bates 1862). Not long after, Müller suggested that there could also be a mutual advantage for two unpalatable species to mimic one another to reduce predator error (Müller 1879). These forms of mimicry, Batesian and Müllerian, are now widely studied, providing broad insights into behaviour, ecology and evolution. Numerous taxa, including both invertebrates and vertebrates, show examples of Batesian or Müllerian mimicry. Bees and wasps provide a particularly interesting case due to the differences in defence between females and males of the same species. While both males and females may display warning colours, only females can sting and inject venom to cause pain and allow escape from predators. Therefore, males are palatable mimics and can resemble females of their own species or females of another species (dual sex-limited mimicry). This asymmetry in defence could have impacts on both population structure and community assembly, yet research into mimicry largely focuses on systems without sex differences. Here, Boutin and colleagues (2023) use a differential equations model to explore the effect of mimicry on population structure and community assembly for sex-limited defended species. Specifically, they address three questions, 1) how do female noxiousness and sex-ratio influence the extinction risk of a single species?; 2) what is the effect of mimicry on species co-existence? and 3) how does dual sex-limited mimicry influence species co-existence? Their results reveal contexts in which populations with undefended males can persist, the benefit of Müllerian mimicry for species coexistence and that dual sex-limited mimicry can have a destabilising impact on species coexistence. The results not only contribute to our understanding of how mimicry is maintained in natural systems but also demonstrate how changes in relative abundance or population structure of one species could impact another species. Further insight into the population and community dynamics of insects is particularly important given the current population declines (Goulson 2019; Seibold et al 2019). References Bates, H. W. 1862. Contributions to the insect fauna of the Amazon Valley, Lepidoptera: Heliconidae. Trans. Linn. Soc. Lond. 23:495- 566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1860.tb00146.x Boutin, M., Costa, M., Fontaine, C., Perrard, A., Llaurens, V. 2022 Influence of sex-limited mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach. bioRxiv, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.21.513153 Goulson, D. 2019. The insect apocalypse, and why it matters. Curr. Biol. 29: R967-R971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.06.069 Müller, F. 1879. Ituna and Thyridia; a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Trans. Roy. Entom. Roc. 1879:20-29. Seibold, S., Gossner, M. M., Simons, N. K., Blüthgen, N., Müller, J., Ambarlı, D., ... & Weisser, W. W. 2019. Arthropod decline in grasslands and forests is associated with landscape-level drivers. Nature, 574: 671-674. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1684-3 | Influence of mimicry on extinction risk in Aculeata: a theoretical approach | Maxime Boutin, Manon Costa, Colin Fontaine, Adrien Perrard, Violaine Llaurens | <p style="text-align: justify;">Positive ecological interactions, such as mutualism, can play a role in community structure and species co-existence. A well-documented case of mutualistic interaction is Mullerian mimicry, the convergence of colour... |  | Biodiversity, Coexistence, Eco-evolutionary dynamics, Evolutionary ecology, Facilitation & Mutualism | Amanda Franklin | 2022-10-25 19:11:55 | View | |

27 Jan 2023

Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunitiesPierre Quévreux, Bart Haegeman and Michel Loreau https://hal.science/hal-03829838How does spatial heterogeneity affect stability of trophic metacommunities?Recommended by Werner Ulrich based on reviews by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko, Ludek Berec and Diogo Provete based on reviews by Phillip P.A. Staniczenko, Ludek Berec and Diogo Provete

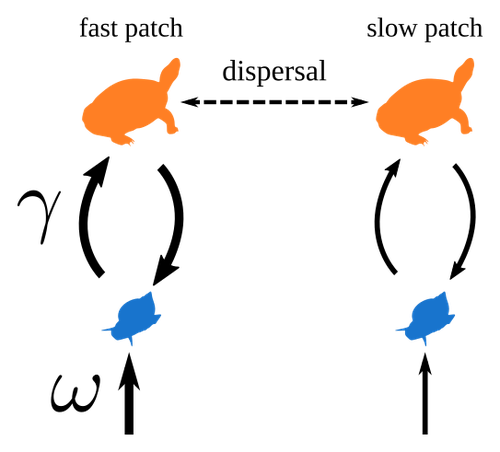

The temporal or spatial variability in species population sizes and interaction strength of animal and plant communities has a strong impact on aggregate community properties (for instance biomass), community composition, and species richness (Kokkoris et al. 2002). Early work on spatial and temporal variability strongly indicated that asynchronous population and environmental fluctuations tend to stabilise community structures and diversity (e.g. Holt 1984, Tilman and Pacala 1993, McCann et al. 1998, Amarasekare and Nisbet 2001). Similarly, trophic networks might be stabilised by spatial heterogeneity (Hastings 1977) and an asymmetry of energy flows along food chains (Rooney et al. 2006). The interplay between temporal, spatial, and trophic heterogeneity within the meta-community concept has got much less interest. In the recent preprint in PCI Ecology, Quévreux et al. (2023) report that Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. These authors rightly notice that the interplay between trophic and spatial heterogeneity might induce contrasting effects depending on the internal dynamics of the system. Their contribution builds on prior work (Quévreux et al. 2021a, b) on perturbed trophic cascades. I found this paper particularly interesting because it is in the, now century-old, tradition to show that ecological things are not so easy. Since the 1930th, when Nicholson and Baily and others demonstrated that simple deterministic population models might generate stability and (pseudo-)chaos ecologists have realised that systems triggered by two or more independent processes might be intrinsically unpredictable and generate different outputs depending on the initial parameter settings. This resembles the three-body problem in physics. The present contribution of Quévreux et al. (2023) extends this knowledge to an example of a spatially explicit trophic model. Their main take-home message is that asymmetric energy flows in predator–prey relationships might have contrasting effects on the stability of metacommunities receiving localised perturbations. Stability is context dependent. Of course, the work is merely a theoretical exercise using a simplistic trophic model. It demands verification with field data. Nevertheless, we might expect even stronger unpredictability in more realistic multitrophic situations. Therefore, it should be seen as a proof of concept. Remember that increasing trophic connectance tends to destabilise food webs (May 1972). In this respect, I found the final outlook to bioconservation ambitious but substantiated. Biodiversity management needs a holistic approach focusing on all aspects of ecological functioning. I would add the need to see stability and biodiversity within an evolutionary perspective. References Amarasekare P, Nisbet RM (2001) Spatial Heterogeneity, Source‐Sink Dynamics, and the Local Coexistence of Competing Species. The American Naturalist, 158, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1086/323586 Hastings A (1977) Spatial heterogeneity and the stability of predator-prey systems. Theoretical Population Biology, 12, 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0040-5809(77)90034-X Holt RD (1984) Spatial Heterogeneity, Indirect Interactions, and the Coexistence of Prey Species. The American Naturalist, 124, 377–406. https://doi.org/10.1086/284280 Kokkoris GD, Jansen VAA, Loreau M, Troumbis AY (2002) Variability in interaction strength and implications for biodiversity. Journal of Animal Ecology, 71, 362–371. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2656.2002.00604.x May RM (1972) Will a Large Complex System be Stable? Nature, 238, 413–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/238413a0 McCann K, Hastings A, Huxel GR (1998) Weak trophic interactions and the balance of nature. Nature, 395, 794–798. https://doi.org/10.1038/27427 Quévreux P, Barbier M, Loreau M (2021) Synchrony and Perturbation Transmission in Trophic Metacommunities. The American Naturalist, 197, E188–E203. https://doi.org/10.1086/714131 Quévreux P, Pigeault R, Loreau M (2021) Predator avoidance and foraging for food shape synchrony and response to perturbations in trophic metacommunities. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 528, 110836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2021.110836 Quévreux P, Haegeman B, Loreau M (2023) Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities. hal-03829838, ver. 2 peer-reviewed and recommended by Peer Community in Ecology. https://hal.science/hal-03829838 Rooney N, McCann K, Gellner G, Moore JC (2006) Structural asymmetry and the stability of diverse food webs. Nature, 442, 265–269. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04887 Tilman D, Pacala S (1993) The maintenance of species richness in plant communities. In: Ricklefs, R.E., Schluter, D. (eds) Species Diversity in Ecological Communities: Historical and Geographical Perspectives. University of Chicago Press, pp. 13–25. | Spatial heterogeneity of interaction strength has contrasting effects on synchrony and stability in trophic metacommunities | Pierre Quévreux, Bart Haegeman and Michel Loreau | <p> Spatial heterogeneity is a fundamental feature of ecosystems, and ecologists have identified it as a factor promoting the stability of population dynamics. In particular, differences in interaction strengths and resource supply between pa... |  | Dispersal & Migration, Food webs, Interaction networks, Spatial ecology, Metacommunities & Metapopulations, Theoretical ecology | Werner Ulrich | 2022-10-26 13:38:34 | View |

MANAGING BOARD

Julia Astegiano

Tim Coulson

Anna Eklof

Dominique Gravel

François Massol

Ben Phillips

Cyrille Violle